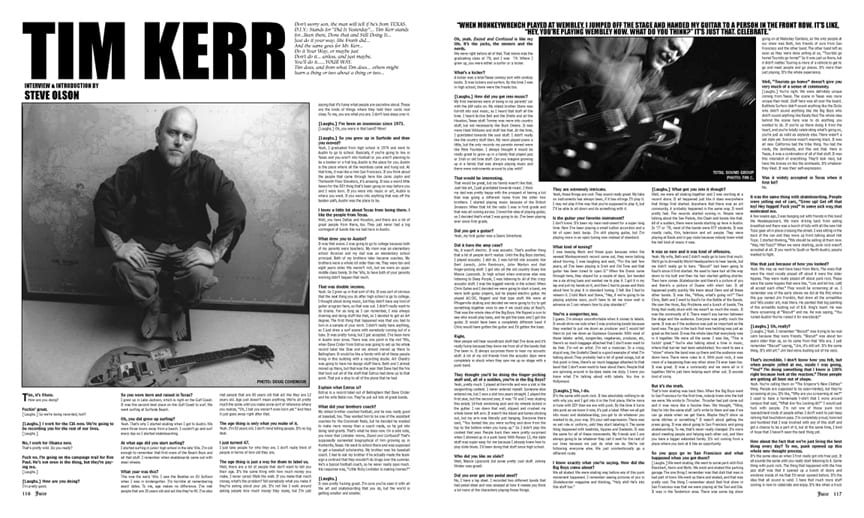

INTERVIEW WITH TIM KERR of the BIG BOYS

INTERVIEW BY STEVE OLSON

INTRODUCTION BY STEVE OLSON

PHOTOS BY DAVE COHENOUR and TIM C.

Don’t worry, son. The man will tell if he’s from TEXAS. D.I.Y.: Stands for ‘Did It Yesterday’… Tim Kerr stands for…Been there, Done that and Still Doing It… Just do it your way, like Frank did… And the same goes for Mr. Kerr… Do it Your Way, or maybe just don’t do it… unless, and just maybe you’ll do it……YOUR WAY. Tim does, and from what Tim does… others might learn a thing or two about a thing or two…

“When Monkeywrench played at Wembley, I jumped off the stage and handed my guitar to a person in the front row. It’s like, “Hey, you’re playing Wembley now. What do you think?” It’s just that. Celebrate.”

Tim, it’s Olson.

How are you doing?

Great.

[Laughs.] So we’re being recorded, huh?

[Laughs.] I work for the CIA now. We’re going to be recording you for the rest of our lives.

[Laughs.]

No, I work for Obama now.

That’s pretty wild. Do you really?

Fuck no. I’m going on the campaign trail for Ron Paul. He’s not even in the thing, but they’re paying me.

[Laughs.]

[Laughs.] How are you doing?

I’m pretty good.

So you were born and raised in Texas?

I grew up in Lake Jackson, which is right on the Gulf Coast. It was the second best place on the Gulf Coast to surf. We went surfing at Surfside Beach.

Oh, you did grow up surfing?

Yeah. That’s why I started skating when I got to Austin. We were three hours away from a beach. I couldn’t go and surf every day so I started skateboarding.

At what age did you start surfing?

I started surfing in junior high school in the late ‘60s. I’m old enough to remember that first wave of the Beach Boys and all that stuff. I remember when skateboards came out with steel wheels.

What year was this?

This was the early ‘60s. I saw the Beatles on Ed Sullivan when I was in kindergarten. I’m horrible at remembering exact dates. To me, age makes no difference. I’ve met people that are 20 years old and act like they’re 90. I’ve also met people that are 80 years old that act like they are 12 years old. Age just doesn’t mean anything. We’re all pretty much the same until you make some sort of reference where you realize, ‘Oh, I bet you weren’t even born yet.’ And then it just goes away right after that.

The age thing is only what you make of it.

Yeah. I’m 52 years old. I don’t mind telling people. It’s no big deal.

I just turned 47.

I just take people for who they are. I don’t really think of people in terms of how old they are.

The age thing is just a way for them to label us.

Well, there are a lot of people that don’t want to tell you their age. It’s the same thing with how much money you make. I never cared. Walk the walk. If you make that much money, what’s the problem? Tell somebody what you make if they’re asking about your job. It’s not like I walk around asking people how much money they make, but I’m just saying that it’s funny what people are secretive about. Those are the kinds of things where they hold their cards real close. To me, you are what you are. I don’t lose sleep over it.

[Laughs.] I’ve been an insomniac since 1973.

[Laughs.] Oh, you were in that band? Wow!

[Laughs.] So you grew up in Surfside and then you moved?

Yeah, I graduated from high school in 1974 and went to Austin to go to school. Basically, if you’re going to live in Texas and you aren’t into football or you aren’t planning to be a banker or a frat boy, Austin is the place for you. Austin is the place where all the weirdoes came and hung out. At that time, it was like a mini San Francisco. If you think about the people that came through here like Janis Joplin and Thirteenth Floor Elevators, it’s amazing. It was a weird little haven for the DIY thing that’s been going on way before you and I were born. If you were into music or art, Austin is where you went. If you were into anything that was off the beaten path, Austin was the place to be.

I know a little bit about Texas from being there. I like the people from Texas.

Well, you have Dallas and Houston, and there are a lot of great people from there, too. They just never had a big contingent of bands like we had here in Austin.

What drew you to Austin?

It was that scene. I was going to go to college because both of my parents were teachers. My mom was an elementary school librarian and my dad was an elementary school principal. Both of my brothers later became coaches. My brothers were a whole lot older than me. They were ten and eight years older. We weren’t rich, but we were an upper middle class family. In the ’60s, to have both of your parents working didn’t happen that much.

That was double income.

Yeah. So I grew up in that sort of life. It was sort of obvious that the next thing you do after high school is go to college. I thought about doing music, but they didn’t have any kind of guitar program here, so that was out. I didn’t really want to do drama. For as long as I can remember, I was always drawing and doing stuff like that, so I decided to get an Art degree. The first thing that happened was that you had to turn in a sample of your work. I didn’t really have anything, so I just drew a surf scene with somebody coming out of a tube. It was pretty funny, but I got accepted. I’ve been here in Austin ever since. There was one point in the mid ’90s, when Dave Crider from Estrus was going to set up his whole record label like Stax and we almost moved up there to Bellingham. It would be like a family with all of these people living in this building with a recording studio. Art Chantry was going to have his design stuff there. Beth and I almost moved up there, but that was the year that Dave had the fire that took out all of the stuff that Estrus had done up to that point. That put a stop to all of the plans that he had.

Explain what Estrus is?

Estrus is a record label out of Bellingham that Dave Crider and his wife Bekki run. They’ve put out lots of great bands.

What did your brothers coach?

My oldest brother coached football, and he was really good at baseball, too. They wanted him to be one of the assistant coaches for the Cincinnati Reds, but he decided he wanted to make more money than a coach made, so he got into doing land grants. That’s what he does now. On a side note, you know that Linklater movie, Dazed and Confused? That’s supposedly somewhat biographical of him growing up in Huntsville, Texas. He went to school there and was supposed to get a baseball scholarship. My brother was his baseball coach. I had to ask my brother if he actually made the team sign a contract that they wouldn’t do drugs over the summer. He’s a typical football coach, so he never really says much. His response was, ‘Little Ricky Linklater is making movies?’

[Laughs.]

It was pretty fucking great. I’m sure you’ve seen it with all the art and skateboarding that you do, but the world is getting smaller and smaller.

Oh, yeah. Dazed and Confused is like my life. It’s the jocks, the stoners and the nerds.

We were right before all of that. That movie was the graduating class of ’78, and I was ’74. Where I grew up, you were either a surfer or a kicker.

What’s a kicker?

A kicker was a total Texas cowboy sort with cowboy boots. It was kickers and surfers. By the time I was in high school, there were the freaks too.

[Laughs.] How did you get into music?

My first memories were of being in my parents’ car with the AM radio on. My oldest brother Steve was full-tilt into soul music, so I heard that stuff all the time. I heard Archie Bell and the Drells and all the Houston, Texas stuff. Tommy was more into country stuff, but not necessarily like Buck Owens. It was

more Hank Williams and stuff like that. At the time, I gravitated towards the soul stuff. I didn’t really like the country stuff then. My mom played piano a little, but the only records my parents owned were like Pete Fountain. I always thought it would be really great to grow up in a family that played jazz or Irish or old time stuff. Can you imagine growing up in a family that was always playing music and there were instruments around to play with?

That would be interesting.

That would be great, but my family wasn’t like that. Just like art, I just gravitated towards music. I think my dad was pretty happy with the prospect of having a kid that was going a different route from the other two brothers. I started playing music because of the British Invasion. When that hit the radio I was in first grade and that was all coming across. I loved the idea of playing guitar, so I decided that’s what I was going to do. I’ve been playing ever since first grade.

Did you get a guitar?

Yeah, my first guitar was a Sears Silvertone.

Did it have the amp case?

No, it wasn’t electric. It was acoustic. That’s another thing that a lot of people don’t realize. Until the Big Boys started, I played acoustic. I still do. I was full-tilt into acoustic like Bert Jansch, John Renbourn, John Martyn and that finger-picking stuff. I got into all the old country blues like Mance Lipscomb. In high school when everyone else was listening to Deep Purple, I was listening to all of this crazy acoustic stuff. I was the biggest weirdo in the school. When Chris Gates and I decided we were going to start a band, we were both guitar players, but he played electric guitar. He played AC/DC, Nugent and that type stuff. We were at Pflugerville skating and decided we were going to try to get something together once to see if we could play at Raul’s. That was the whole idea of the Big Boys. We flipped a coin to see who would play bass, and he got the bass and I got the guitar. It would have been a completely different band if Chris would have gotten the guitar and I’d gotten the bass.

Right.

Now people will hear soundtrack stuff that I’ve done and it’s really funny because they know me from all of the bands that I’ve been in. It always surprises them to hear my acoustic stuff. A lot of my old friends from the acoustic days were completely in shock when they saw me up on stage with a punk band.

They thought you’d be doing the finger-picking stuff and, all of a sudden, you’re in the Big Boys?

Yeah, pretty much. I played at Kerrville and won a slot in the songwriting contest. I never entered myself. Someone else entered me, but I won a slot two years straight. I played the first year, but the second year, it was ’76 and I was skating this empty 14-foot swimming pool and my wheels locked in the gutter. I ran down that wall, slipped and crushed my whole lower left arm. It wasn’t like blood and bones sticking out, but my arm was literally just hanging. Everyone there said, ‘You looked like you were surfing and dove from the top to the bottom when you hung up.’ So I didn’t play the contest that year. People back then were pretty surprised when I showed up in a punk band. With Poison 13, the slide stuff was super easy for me because I already knew how to play slide blues. I’d been doing that stuff since high school.

Who did you like on slide?

Well, Mance Lipscomb did some pretty cool stuff. Johnny Winter was great!

Did you ever get into pedal steel?

No, I have a lap steel. I recorded two different bands that had pedal steel and was amazed at how it makes you think a lot more of the characters playing those things.

They are extremely intricate.

Yeah, those things are cool. They sound really great. My take on instruments has always been, if it has strings I’ll play it. I may not play it the way that you’re supposed to play it, but I’ll be able to sit down and do something with it.

Is the guitar your favorite instrument?

I don’t know. It’s been my main instrument for a super long time. Now I’ve been playing a small button accordion and a lot of open back banjo. I’m still playing guitar, but I’m playing more in an open tuning now instead of standard.

What kind of tuning?

I was teasing Mark and those guys because when the newest Monkeywrench record came out, they were talking about touring. I was laughing and said, ‘For the last few years, all I’ve been playing is Irish and Old Time and that guitar has been tuned to open D.’ When the Evens came through here, they stayed for a couple of days. Ian handed me a six string bass and wanted me to play it. I got it in my lap and put my hands on it, and then I had to pause and think about how to play it in standard tuning. I felt like I had to relearn it. I told Mark and Steve, ‘Hey, if we’re going to be playing anytime soon, you’ll have to let me know well in advance so I can relearn how to play standard.’

You’re a songwriter, too.

I guess. I’m always uncomfortable when it comes to labels. It would drive me nuts when I was producing bands because they wanted to put me down as producer and I would tell them to put me down as Guidance Counselor. With most of those labels: artist, songwriter, vegetarian, producer, etc, there’s so much baggage attached that I don’t even want to be that. I’m not an artist. I’m not a musician. In a crazy, stupid way, the Grateful Dead is a good example of what I’m talking about. They probably had a lot of great songs, but at this point in time, there’s so much baggage attached to that band that I don’t even want to hear about them. People that are spinning around in tie-dyes make me dizzy. I know you know what I’m talking about with labels. You live in

Hollywood.

[Laughs.] Yes, I do.

It’s the same with punk rock. It has absolutely nothing to do with why you and I got into it in the first place. We’re more in tune with DIY than we are with punk. By the time it turns into punk as we know it now, it’s just a label. When we all got into music and skateboarding, you got to do whatever you wanted to do, your way. It’s your self-expression. There was no set rule or uniform, until they start labeling it. The same thing happened with beatniks, hippies and Dadaists. It was the same for all of these movements. My friends and I are always going to be whatever they call it next for the rest of our lives because we just do what we do. We’re not following everyone else. We just unintentionally go a different route.

I know exactly what you’re saying. How did the Big Boys come about?

We all skated. We were skating way before any of this punk movement happened. I remember seeing pictures of you in Skateboarder magazine and thinking, ‘Holy shit! He’s into this stuff too.’

[Laughs.] What got you into it though?

Well, we were all skating together and I was working at a record store. It all happened just like it does everywhere that things first started. Anywhere that there was an art community, it probably happened in the same way. It went pretty fast. The records started coming in. People were talking about the Sex Pistols, the Clash and bands like that. All of a sudden, there were bands starting up here in Austin. In ’77 or ’78, most of the bands were RTF students. It was mostly radio, film, television and art people. They were playing at Rauls and in gay clubs because nobody knew what the hell kind of music it was.

It was so new and it was kind of offensive.

Yeah. My wife, Beth and I didn’t really go to bars that much. We’d go to Armadillo World Headquarters to hear bands, but we didn’t really go to bars. ‘Biscuit’ had been going to Raul’s since it first started. He used to have hair all the way down to his butt and then his hair started getting shorter. Then here comes Skateboarder and there’s a picture of you and there’s a picture of Duane with short hair. It all happened pretty quickly. We knew about Devo and all these other bands. It was like, ‘Whoa, what’s going on?’ Then Chris, Beth and I went to Raul’s for the Battle of the Bands. We saw the Huns, Boy Problems and a bunch of bands. The thing that really stuck with me wasn’t so much the music. It was the community of it. There wasn’t any barrier between the stage and the audience. Everyone was pretty much the same. It was as if the audience was just as important as the band was. The guy in the back that was heckling was just as great as the band. It was the whole idea that everybody was in it together. We were all the same. I was like, ‘This is fuckin’ great.’ You’re also talking about a time in music, where that barrier had been established. You went to see a ‘show’ where the band was up there and the audience was down here. There were rules to it. With punk rock, it was more of a happening than any other show I’d ever been too. It was great. It was a community and we were all in it together. We’re just here helping each other out. It sounds kind of corny.

But it’s the truth.

That’s how skating was back then. When the Big Boys went to San Francisco for the first time, nobody knew who the hell we were. We wrote to Thrasher. Thrasher had just come out and it was more like a fanzine then. We thought, ‘Wow, they’re into the same stuff. Let’s write to them and see if we can go skate when we get there. Maybe they’ll show us some ditches or something.’ It wasn’t about getting the press going. It was about going to San Francisco and going skateboarding. To me, that’s never really changed. It’s more about meeting people and helping each other out, and then you have a bigger extended family. It’s not coming from a place where you look at it like an opportunity.

So you guys go to San Francisco and what happened when you got there?

[Laughs.] We went skating. We went to some park with Rick Blackhart, Kevin and Mofo. We went and skated this parking garage. The one thing I remember was that dish that was in bad part of town. We went up there and skated, and that was pretty cool. The thing I remember about that first show in San Francisco was that we were playing at the Tool and Die. It was in the Tenderloin area. There was some big show going on at Mabuhay Gardens, so the only people at our show was Beth, two friends of ours from San Francisco and the other band. The other band left as soon as they were done yelling at us, ‘Tourists go home! Tourists go home!’ So it was just us there, but it didn’t matter. Touring is more of a vehicle to get to go and meet people and go places. It’s more than just playing. It’s the whole experience.

Well, ‘Tourists go home’ doesn’t give you very much of a sense of community.

[Laughs.] You’re right. We were definitely unique coming from Texas. The scene in Texas was more unique than most. Stuff here was all over the board. Butthole Surfers didn’t sound anything like the Dicks who didn’t sound anything like the Big Boys who didn’t sound anything like Really Red. The whole idea behind the scene here was to do anything you wanted to do. If you’re up there doing it from the heart, and you’re totally celebrating what’s going on, you’re just as valid as anybody else. There wasn’t a set style yet. Everyone wasn’t wearing black. It was all new. California had the tribe thing. You had the mods, the skinheads, and this and that. Here in Texas, it was a combination of all of that stuff. It was this mismatch of everything. They’d look mod, but have the braces on like the skinheads. It’s whatever they liked. It was their self-expression.

FOR THE REST OF THE STORY, ORDER ISSUE #65 BY CLICKING HERE…

SHARE THIS POST:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)