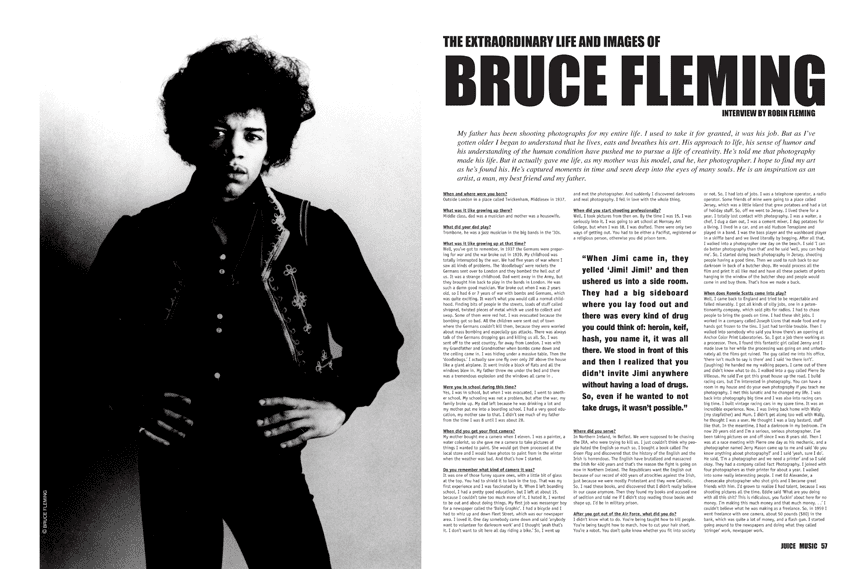

THE EXTRAORDINARY LIFE AND IMAGES OF BRUCE FLEMING

INTERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION BY ROBIN FLEMING

My father has been shooting photographs for my entire life. I used to take it for granted, it was his job. But as I’ve gotten older I began to understand that he lives, eats and breathes his art. His approach to life, his sense of humor and his understanding of the human condition have pushed me to pursue a life of creativity. He’s told me that photography made his life. But it actually gave me life, as my mother was his model, and he, her photographer. I hope to find my art as he’s found his. He’s captured moments in time and seen deep into the eyes of many souls. He is an inspiration as an artist, a man, my best friend and my father.

When and where were you born?

Outside London in a place called Twickenham, Middlesex in 1937.

What was it like growing up there?

Middle class, dad was a musician and mother was a housewife.

What did your dad play?

Trombone, he was a jazz musician in the big bands in the ’30s.

“WHEN JIMI CAME IN, THEY YELLED, “JIMI! JIMI!” AND THEN USHERED US INTO A SIDE ROOM. THEY HAD A BIG SIDEBOARD WHERE YOU LAY FOOD OUT AND THERE WAS EVERY KIND OF DRUG YOU COULD THINK OF: HEROIN, KEIF, HASH, YOU NAME IT, IT WAS ALL THERE. WE STOOD IN FRONT OF THIS AND THEN I REALIZED THAT YOU DIDN’T INVITE JIMI ANYWHERE WITHOUT HAVING A LOAD OF DRUGS. SO, EVEN IF HE WANTED TO NOT TAKE DRUGS, IT WASN’T POSSIBLE.”

What was it like growing up at that time?

Well, you’ve got to remember, in 1937 the Germans were preparing for war and the war broke out in 1939. My childhood was totally interrupted by the war. We had five years of war where I saw all kinds of problems. The doodlebugs were rockets the Germans sent over to London and they bombed the hell out of us. It was a strange childhood. Dad went away in the Army, but they brought him back to play in the bands in London. He was such a damn good musician. War broke out when I was 2 years old, so I had 6 or 7 years of war with bombs and Germans, which was quite exciting. It wasn’t what you would call a normal childhood. Finding bits of people in the streets, loads of stuff called shrapnel, twisted pieces of metal which we used to collect and swap. Some of them were red hot. I was evacuated because the bombing got so bad. All the children were sent out of town where the Germans couldn’t kill them, because they were worried about mass bombing and especially gas attacks. There was always talk of the Germans dropping gas and killing us all. So, I was sent off to the west country, far away from London. I was with my Grandfather and Grandmother when bombs came down and the ceiling came in. I was hiding under a massive table. Then the doodlebugs. I actually saw one fly over only 20 feet above the house like a giant airplane. It went inside a block of flats and all the windows blew in. My father threw me under the bed and there was a tremendous explosion and the windows all came in.

Were you in school during this time?

Yes, I was in school, but when I was evacuated, I went to another school. My schooling was not a problem, but after the war, my family broke up. My dad left because he was drinking a lot and my mother put me into a boarding school. I had a very good education, my mother saw to that. I didn’t see much of my father from the time I was 8 until I was about 28.

When did you get your first camera?

My mother bought me a camera when I eleven. I was a painter, a water colorist, so she gave me a camera to take pictures of things I wanted to paint. She would get them processed at the local store and I would have photos to paint from in the winter when the weather was bad. And that’s how I started.

Do you remember what kind of camera it was?

It was one of those funny square ones, with a little bit of glass at the top. You had to shield it to look in the top. That was my first experience and I was fascinated by it. When I left boarding school, I had a pretty good education, but I left at about 15, because I couldn’t take too much more of it. I hated it, I wanted to be out and about doing things. My first job was messenger boy for a newspaper called the “Daily Graphic”. I had a bicycle and I had to whiz up and down Fleet Street, which was our newspaper area. I loved it. One day somebody came down and said ‘Anybody want to volunteer for darkroom work?’ I thought, ‘Yeah that’s it. I don’t want to sit here all day riding a bike.’ So, I went up and met the photographer. And suddenly I discovered darkrooms and real photography. I fell in love with the whole thing.

When did you start shooting professionally?

Well, I took pictures from then on. By the time I was 15, I was seriously into it. I was going to art school at Hornsey Art College, but when I was 18, I was drafted. There were only two ways of getting out. You had to be either a Pacifist, registered or a religious person, otherwise you did prison term.

Where did you serve?

In Northern Ireland, in Belfast. We were supposed to be chasing the IRA, who were trying to kill us. I just couldn’t think why people hated the English so much so, I bought a book called The Green Flag and discovered that the history of the English and the Irish is horrendous. The English have brutalized and massacred the Irish for 400 years and that’s the reason the fight is going on now in Northern Ireland. The Republicans want the English out because of our record of 400 years of atrocities against the Irish, just because we were mostly Protestant and they were Catholic. So, I read these books, and discovered that I didn’t really believe in our cause anymore. Then they found my books and accused me of sedition and told me if I didn’t stop reading those books and shape up, I’d be in military prison.

After you got out of the Air Force, what did you do?

I didn’t know what to do. You’re being taught how to kill people. You’re being taught how to march, how to cut your hair short. You’re a robot. You don’t quite know whether you fit into society or not. So, I had lots of jobs. I was a telephone operator, a radio operator. Some friends of mine were going to a place called Jersey, which was a little island that grew potatoes and had a lot of holiday stuff. So, off we went to Jersey. I lived there for a year. I totally lost contact with photography. I was a waiter, a chef, I dug a dam out, I was a cement mixer, I dug potatoes for a living. I lived in a car, and an old Hudson Terraplane and played in a band. I was the bass player and the washboard player in a skiffle band and we lived literally by begging. After all that, I walked into a photographer one day on the beach. I said, ‘I can do better photography than that’ and he said, “Well, you can help me.” So, I started doing beach photography in Jersey, shooting people having a good time. Then we used to rush back to our darkroom in back of a butcher shop. We would process all the film and print it all like mad and have all these packets of prints hanging in the window of the butcher shop and people would come in and buy them. That’s how we made a buck.

When does Ronnie Scotts come into play?

Well, I came back to England and tried to be respectable and failed miserably. I got all kinds of silly jobs, one in a potentometry company, which sold pits for radios. I had to chase people to bring the goods on time. I had these shit jobs. I worked in a company called Joseph Lions that made food and my hands got frozen to the tins. I just had terrible trouble. Then I walked into somebody who said you know there’s an opening at Anchor Color Print Laboratories. So, I got a job there working as a processor. Then, I found this fantastic girl called Jenny and I made love to her while the processing was going on and unfortunately all the films got ruined. The guy called me into his office, “There isn’t much to say is there?” I said, “No there isn’t.” (laughing) He handed me my walking papers. I came out of there and didn’t know what to do. I walked into a guy called Pierre De Vilieous. He said I’ve got this great house up the road, I build racing cars, but I’m interested in photography. You can have a room in my house and do your own photography if you teach me photography. I met this lunatic and he changed my life. I was back into photography big time and I was also into racing cars big time. I built vintage racing cars in my spare time. It was an incredible experience. Now, I was living back home with Wally (my stepfather) and Mum. I didn’t get along too well with Wally, he thought I was a user. He thought I was a lazy bastard, stuff like that. In the meantime, I had a darkroom in my bedroom. I’m now 20 years old and I’m a serious, serious photographer. I’ve been taking pictures on and off since I was 8 years old. Then I was at a race meeting with Pierre one day as his mechanic, and a photographer named Jerry Mason came up to me and said, “Do you know anything about photography?” I said, “Yeah, sure I do.” He said, “I’m a photographer and we need a printer.” So I said okay. They had a company called Fact Photography. I joined with four photographers as their printer for about a year. I walked into some really interesting people. I met Ed Alexander, a cheesecake photographer who shot girls and I became great friends with him. I’d grown to realize I had talent, because I was shooting pictures all the time. Eddie said, “What are you doing with all this shit? This is ridiculous, you fuckin about here for no money. I’m making this much money and that much money…” I couldn’t believe what he was making as a freelance. So, in 1959 I went freelance with one camera, about 50 pounds ($80) in the bank, which was quite a lot of money, and a flash gun. I started going around to the newspapers and doing what they called “stringer” work, newspaper work.

When was the first time you got published?

The first picture I had published was in the Jazz News in 1960. It was a striking shot of a guy call Ronnie Ross who was a baritone player and it was my first picture and I got two English pounds for it. I went out into the square, when I picked up a copy of it from the publisher and cried my eyes out because I’d finally been published. It said, “This striking shoot by up-and-coming jazz photographer Bruce Fleming.” Now, I got my first by-line.

Tell me about Ronnie Scott’s?

Yes. Well, Ronnie Scott’s is the most amazing and purest jazz club in London, probably in the whole of the United Kingdom. I hung around Ronnie’s five nights a week.

How’d you get your foot in the door there?

I just went in there with a press card from the Melody Maker, who I’d started to work with. That was a tough job to get. They had five of their own staff photographers, but I wanted to work for them. So, I sat on their steps everyday. They used to step over me in the morning. I’d be there at 9 o’clock waiting. They’d say, “You still here?” And I’d say “Yeah, I’m waiting for a job.” I never thought I’d make it, then one day the door opened and a girl came out and said the editor wants to see you. So, I went in and he said, “You’ve got to go to Talk Of The Town and photograph Eartha Kitt. And I don’t want the usual shit, I want something different.” So, I went with my little camera. I was so nervous that I just stood there. Eartha Kitt was an amazing lady and after a bit there were about 50 photographers. Suddenly at the end of it, she looked over and said, “What’s the matter with you, son? Don’t you want to take my picture?” I said, “Yeah, but I don’t wanna to do what all the others have done.” She said, “I dig that, I like that.” Then the other guys are saying, “No, no, no, it’s all finished now.” She says, “No, it’s not, give the kid a chance.” So, she says, “What do you want me to do?” She had a leopard skin coat on, so I said, “Throw it on the stairs and lie on it.” So, she threw it on the stairs and lay down on it. Everyone is going, “No, don’t do that.” But, I got the picture. The editor went crazy, “This is a great picture.” I got front page and 30 pounds, which is an awful lot of money, and I started working for them regularly. I go down to Ronnie’s with my press pass and meet Pete King and Ronnie. They know I am a serious photographer, except when I start drinking, then I am a serious drinker. I was down there five nights a week with Chet Baker, Dexter Gordan, Zoot Sims, Trevor and Young. Every kind of jazz man who played the big concerts would come there afterwards and jam. It was absolutely brilliant.

What happened next?

I was still shooting press photography and then somebody stuck a knife in me and damn near killed me. I decided that discretion was a better part of valor. I decided to get out of the press game after I was beaten up a couple of times and stabbed by somebody who did not want to be photographed. I did my last job in about 1965, the funeral of Sir Winston Churchill. I did that for the Sunday Times and that was my last press job. Then I walked into David Block and I became great friends with him through the music business. He was working for the most famous public relations man in London so he took me on as his photographer. From then on, I met people like The Rolling Stones, the Dave Clark Five. I became their personal photographer. I met Jimi Hendrix and I became his photographer. I was the first to photograph The Animals with Eric Burton when they came down from New Castle. Chas Chandler became a great friend and that’s how I met Jimi. He was Jimi’s manager. I met lots of famous people like Richard Burton and Liz Taylor through this guy, David Block. He shortened my problems of getting into the business, because I met so many people. They all liked my photographs, so I did very well.

What was it like the first day you met Jimi?

That was in 1966. I got a call from Chas Chandler who was playing lead guitar in The Animals. Eric Burton was the lead singer, I think he’s still singing. He rang me and said, “Bruce, come over to the office. There’s this new guy in town called Jimi Hendrix.” I had never heard of him, nobody had. So, I went to the office in Soho and there’s this tall guy with wired hair. We start talking and Chas said to me, “This guy is amazing.” Now, I’ve heard all of this shit before. Everybody who came into London was amazing. I found that most of them were pigs, trashing rooms, throwing TV sets through windows, throwing their managers through windows, driving over people, killing people, switchblade knife enthusiasts, druggies. They were all fuckin mental. We were into the hippy thing then, so everybody was smoking dope. If you didn’t have a stash or a joint in your hand then fuck you. Then I met this black guy, who’s very calm and very quiet and very funny and we hit it off and I started shooting him.

What was your first assignment with him?

His record cover in March 1967, Are You Experienced? I’m sending that to a gallery in San Francisco this week. No one has ever seen this picture before. It’s a huge Irish print- about 16 x 16 on water color paper. They’re gonna ask something like $2,200 for it.

Tell me about Hendrix.

He was terrific. This is the amazing thing. When I first met him he was so calm and quiet. If he didn’t understand you, he’d say, ‘Pardon me.’ Then I went to one of his concerts. I couldn’t believe it. He was Jekyll and Hyde. He was so quiet off stage, so nice and kind and responsive and then he got on stage and the sheer power of his personality and his playing ability hit you like a ton of bricks. It was like standing in front of the sun without any clothes on, on a hot day. It just blew your fucking mind and I realized the power of him. He had this massive, massive power. It was kind of hypnotic, and he had a fantastic way of playing. He was into art and destruction. There was an anger in the playing, not in his personality or when you talked to him, but anger in the playing. A powerhouse anger against being black and being put down by whites and against war. He hated war and he hated violence and he became an artist who essentially was very avant-garde. He was a brilliant player. A lot of guitarists used to go and watch him, but still couldn’t figure out how he did things, ‘cause he was so amazing with his fingers. He was an amazing player, plus he was left handed which was crazy. One day I was with him on a recording session and a guy was trying to play something and Jimi said, ‘No, no like this’ and he took the guy’s guitar put it upside down and played it upside down. He played it better upside down than the guy could play it. He was one of the world’s greatest guitar players.

What was he interested in, when he got to England? How did he perceive England as opposed to America?

We were in the underground so he never really saw too much of above ground. I think he knew there was a class system and he was aware of that. But he was a musician. He was only really interested in music. He liked girls, he liked drinking, he liked drugs, we all did, but his primary interest was music, he loved it. Chas told me that when he brought him over from the states, Jimi just lived with Chas in a little flat, nothing special. Chas said that he used to get up in the morning, put the guitar around his neck, start playing, walk over to the coffee maker and make some coffee. Or he would go in the bathroom, sit down and have a shit and be playing in the toilet. This was a guy who was serious about playing.

FOR THE REST OF THE STORY, ORDER ISSUE #50 BY CLICKING HERE…

SHARE THIS POST:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

One Response