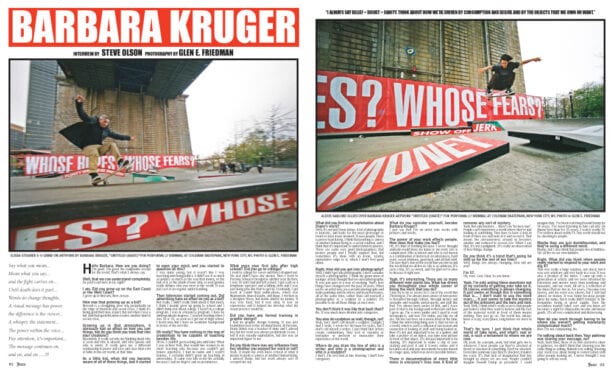

EXCLUSIVE STORY & INTERVIEW WITH BARBARA KRUGER FROM JUICE MAGAZINE #76 ARCHIVES

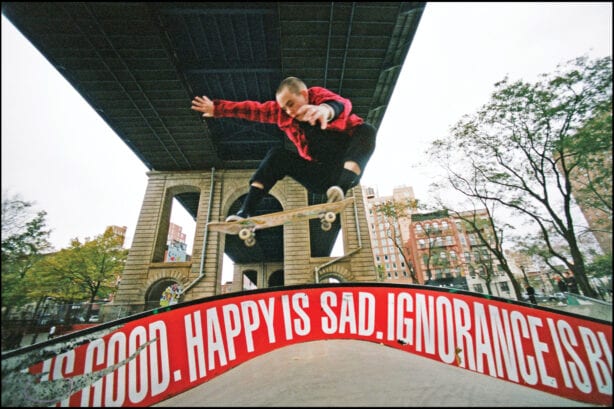

Performa Biennial Celebrated The Work of Barbara Kruger: Public Art Action at LES Skatepark in NYC

Words by Sasha Okshteyn

The Performa Biennial is a three-week, city-wide festival dedicated to live performances across artistic disciplines. In 2017, the biennial project that I was working on was a multipart performance by contemporary artist, Barbara Kruger. Using her instantly recognizable white-on-red Futura typeface, Kruger inserted her work into the street culture that has absorbed, appropriated and applied her provocative attitude and approach over the last few decades through her first live performance, and a series of public art actions – one being a full vinyl wrap of LES skatepark in downtown Manhattan, with the help of one of New York’s skateboarding powerhouses, Steve Rodriguez. Once we started rolling it out, the installation was bold and pulled no punches. Seeing the red and white graphics plastered all over the elements of the park, you can imagine what all of the park kids thought when they entered LES – NO, it’s NOT Supreme! But what is it?

Over the years, I would run into Glen E. Friedman at book signings, film premieres, and photo shows around the city – and I learned more and more about his legendary status across skateboarding, punk and hip-hop. When he strolled into the Performa Biennial Hub in SoHo that my colleagues and I created as the center of the Barbara Kruger performance, I saw a unique opportunity for Glen to join forces with other creative figures for a dynamic conversation about art, community and skateboarding.

Glen walked right into the midst of conversations we had been having with Kruger about her influence on the fashion industry and what she felt was important to voice through her Performa project. She had mentioned that one of her visions with the park was to celebrate women skaters in a such a male dominant space and the wish to capture them shredding over her bold messages grounded in activism, feminism and community. Not only did Glen get excited to join the audience watching Kruger realize her vision, but he wanted to document it and be a part of it.

At that same moment, I had convinced a group of women skaters from different eras and points of creative influence to be a part of a conversation within Kruger’s project. I had seen skater Jilleen Liao host an event tied to her small business, footwear line, Onto NYC, with a segment of a conversation series called Heavy Discussion about women in the skate industry. It reverberated on a similar wavelength to what Kruger was thinking about, so I asked Liao if she would bring a part of the series into the Biennial. On November 18th, at the Performa Biennial Hub, she led the conversation as moderator, with Alexis Sablone, Kea Duarte, Jaime Reyes, Sara Kay, Lacey Baker, and Elissa Steamer, exploring points raised by Kruger’s project in the panel.

I asked Glen if he would want to shoot the Heavy Discussion crew at LES as documentation tied to Kruger’s vision and, to my surprise, not only did he say yes, but he immediately called Steve Olson to push things further by doing a Juice Magazine interview with Kruger. In just a few days, we got organized and met at LES for a skate session with Glen and the crew.

Even though it was a brutally cold day in New York City, Glen embraced the spirit of the moment – pivoting from Kruger’s messaging to capturing Alexis’ push up and ollie over MONEY TALKS and Elissa’s five-o across WHOSE VALUES? WHOSE JUSTICE? That feeling has extended even further now because, whereas performance – like skate tricks – is often in the moment and then gone, with Glen’s photographs and this interview between Olson and Kruger, people asking questions and participating in Kruger’s provocations can be passed forward.

For anyone looking to fuck up the status quo, break down the walls that hold us in, or to ride up them – that’s what you hope for.

BARBARA KRUGER

INTERVIEW BY STEVE OLSON

PHOTOGRAPHY BY GLEN E. FRIEDMAN

Say what you mean…

Mean what you say…

and the fight carries on…

Until death does it part…

Words do change thoughts,

A visual message has power,

the difference is the viewer…

A whisper, the statement…

The power within the voice…

Pay attention, it’s important…

The message continues on,

and on, and on……!!!

Hello Barbara. How are you doing?

I’m good. I’m good. No complaints except for the world. That’s what I always say.

Well, that we can understand completely.

So you’re out here in LA, right?

I am. Did you grow up on the East Coast or the West Coast?

I grew up in Newark, New Jersey.

How was that growing up as a kid?

Newark is a struggling, poor city, perpetually on the edge of financial and social crisis. I think it’s being gentrified now, in part, but not when I was a kid. And that gentrification creates another kind of social crisis.

Growing up in that atmosphere, it obviously had an effect on how you saw things, but do you think you took that into your creations?

Absolutely. It really set into my thinking about who is seen and who is absent, and who speaks and who is silent. It really gave me a different relationship to power and race and class than a lot of folks in the art world, at that time.

As a little kid, when did you become aware of all of these things, and it started to open your mind, and you started to question all this?

I was quite young, but it wasn’t like I was marching and doing politics. I didn’t see it so much as politics as much as the way that money, or the lack of it, or the shade of your skin, or your gender, really defines who you were in the world. It was just sort of an organic understanding.

Then television started coming out. Did advertising have an effect on you as a kid?

Not really. I didn’t really think about it that much. I think I mainly grew up going to school and I didn’t think a lot about college. I wasn’t in a college program. I was in a business program. I have no undergraduate degrees. I started working when I was 18 or 19, as soon as I got out of high school. I teach now, but I have no academic background in terms of my own life.

Oh really? You have nothing in the way of credentials to be capable of teaching besides life.

Oh no. I couldn’t get teaching jobs until later. When I was in New York, they would hire women to do short teaching jobs because you couldn’t get tenure anywhere. I had no name and I wasn’t famous. I certainly didn’t grow up teaching at universities. It came very late in my life actually, because I had no degree and no prominence.

What were your first jobs after high school? Did you go to college?

I went to college for a year and then I dropped out. We just didn’t have any money. Then I went to Parsons School of Design for another year. By then, I was 18 and I had just left school. I got a job as a telephone operator and a billing clerk and I was just doing jobs like that to get by. Eventually, I got work at Condé Nast publications, which was Mademoiselle, House & Garden, and Vogue. I worked as a designer there, but made almost no money. It was very hard, but it was okay. It was an experience and it helped me develop what my visual practice would be.

Did you have any formal training in graphic design?

I had no graphic design training. It was just foundation year in the art department. At Parsons, Diane Arbus was a teacher of mine and I adored her, but her work was always problematic to me. I felt it was visually exploitative, but she was an important figure to me.

Do you think there was any influence from her, whether you enjoyed her work or not?

Yeah. It made me even more critical of what it means to point a camera at another human being. I adored Diane, but her work always sort of creeped me out.

What did you find to be exploitative about Diane’s work?

Well, it’s not just Diane Arbus. A lot of photography is touristic, and looks for the most grotesque or weird or most ironic moment. It uses people. There is power in picturing. I think that pointing a camera at another human being is a social relation, and I think that it’s important to understand its powers. There are some very good photographers that picture people and I totally support that, but sometimes it’s done with an ironic, snarky, exploitative edge to it, which I don’t feel good about.

Right. How did you get into photography?

Well, I don’t consider myself a photographer. I think my generation of younger artists thought that we used photography. It was just part of a way of working. That’s how things have changed over the past 30 years. When you’re an artist now, you can take photographs and make paintings and do videos and do performance, all at the same time, rather than call yourself a photographer or a sculptor or a painter. It’s possible to do all those things at once now.

You don’t think it was like that back then?

No. It was much more divided into categories.

You also do sculpture as well, though, no?

Yeah, but I don’t call myself a sculptor. [laughs] And I write, I wrote for Art Forum for years, but I don’t call myself a writer. I just think that artists create commentary. They sort of visualize or textualize or perform or musicalize their experience of the world.

Where do you draw the line of who is a writer and who is a photographer and who is a sculptor?

I don’t. I’m very bad at line drawing. I don’t love categories.

What do you consider yourself, besides Barbara Kruger?

I just say that I’m an artist who works with pictures and words.

The power of your work affects people. How does that make you feel?

Oh, it’s kind of thrilling because I never thought anybody would know my name or my work. Life is complicated. Who is known and who is not known is a combination of historical circumstances, hard work, social relations, good luck, and all that stuff. I’m sure that’s true in the world that you live in and the world that we all live in. Life is so arbitrary. It’s such a trip. It’s so weird, and I’m glad we’re alive to discuss it right now.

Yeah. It’s interesting. There are so many different viewpoints too. What has driven you throughout your whole career of doing the work that you do?

I just try to be as aware as I can of the world that I’m living in. I’ve always been aware of how power is threaded through culture, through money and sexuality and visuality and property, and stuff like that. I’ve always been aware of that, and I trace part of that to my background in Newark and how I grew up. I’m a news junkie and I used to read newspapers, and now I’m online, just like we all are. We live our lives on screens most of the time. I think the interesting thing now is that we live in a world, which is such a collision of narcissism and voyeurism of looking at stuff and being looked at. Now it’s not just important to be at a gallery and take a picture of an object, you take your picture in front of that object. It’s not just important to be skating. It’s important to make a clip of your skating and post it and it travels online and it becomes viral and your movements become known in a huge span, which was never possible before.

There is documentation of every little move in everyone’s lives now. It kind of removes any sort of mystery.

Yeah. Not only mystery… there’s no ‘be here now’. People can’t experience a world where they’re just looking at something. They have to have a lens in front of their eye and look at it and record it. That means the awesomeness around us becomes smaller and reduced to screen size. When I say that, it’s not a judgment. It’s really an observation of how things change.

Do you think it’s a trend that’s going be with us for the rest of our lives?

Well, things are always changing. How old are you?

I’m 57.

Oh, wow. Cool. Okay. So you know.

Yeah. I’m only asking these questions out of my curiosity of getting your take on it. Of course, everything is always changing. It just seems as though this is something that is… I don’t want to use the word scary…. It just seems to take the mystery out of the unknown and the here and now.

Yeah. Well, I think what’s really scary is that people just believe what they want to believe and the fact of the material world in front of them means nothing. They just go on. The world has always been a crazy, scary place, long before we were in it.

That’s for sure. I just think that whole world of fake news, and what’s real or not, is such a testament to where we are now.

Oh, yeah. As a people, yeah, but what gets me is whenever I hear people say they’re shocked at Brexit or shocked at something. Don’t be shocked. Every time someone says they’re shocked, it makes me crazy. It’s that lack of imagination that has brought us where we are now. People couldn’t imagine Donald Trump as president. I could imagine that. I’ve been watching Donald Trump for 30 years. I’ve been listening to him call into The Howard Stern Show for 25 years. I watch reality TV. I’ve written about reality TV. This world should not be shocking to people.

Maybe they are just dumbfounded, and they’re using a different word.

Maybe, but I also think that people live in bubbles. We all live in our own bubbles.

Right. What did you think when people really started to respond to your work and dig it?

That was really a huge surprise, not shock, but it was very arbitrary and very lucky in a way. It was also a product of the times. I came up with a generation of artists and we were informed by television and movies more than paintings and museums, and our work. All art is a reflection of the times that we live in. For years, I became very known, and my work was shown, but I still had almost no money. It was funny because people knew my name, but it really didn’t transfer to the Benjamins being in great supply. Then the secondary market takes over and you know art becomes a site for disposable income and luxury goods. It’s all very complicated and distressing.

How do you work through having to be where you weren’t getting monetarily compensated much?

Now I’m not complaining. No.

I’m talking about back then. Your pathway was sharing your message, no?

Yeah. Back then, those of us who started to show in galleries, we didn’t think that showing was the same thing as selling. Nobody was selling. Showing your work was about being in conversation with other people making art. I never thought I was going to sell my work.

Where did you sell your first piece of art?

It was in a commercial gallery, in 1981.

Oh, really? It was that late?

Oh yeah. I worked for years in anonymity. I teach young kids now who think that they’re going to get out of school and have shows and sell art right away. For me, it was a while. That’s why I took all of these visiting artists jobs because I couldn’t afford to stay and live in New York. I taught at Ohio State and CalArts and the Art Institute of Chicago and Berkeley, for six months at a time. I didn’t have much of a career, but at least I could pay my rent back in New York. Again, I have no complaints now, but I had no inheritance or family money. I think what has changed for the better now is that, when I first started coming up, the art world was 12 white guys in lower Manhattan. Thank goodness it’s much different now. Back then very few artists could support themselves through their work.

Yeah. That’s a trick in itself.

Sure. Everyone I knew at that time, and even now, a lot of my peers have jobs if they can get them. They’re teaching or working in the industries out here. That’s just the way it is. I’ve been very fortunate. I want to make it clear. I have no complaints now, but I never thought I’d have a pot to piss in. Now I’m the first person in my family to ever own property. No one in my family ever owned property. I grew up in a three-room apartment in northern New Jersey. My life has taken really surprising, fortunate turns.

When did you make the move to Manhattan?

I moved to Manhattan when I went to Parsons. I lived in a dorm for a year, and then I got an apartment. That was in ’67 or ’68. I started working at Condé Nast in ’69. I was a kid without any degrees or anything like that. I was quite young.

You obviously had some kind of drive where they realized they should bring you on.

No. I didn’t even know what it meant to be an artist. It was too intimidating, the art world, and there were hardly any women. The turnover at Condé Nast was huge and they paid you nothing. Most of the people that worked there were of wealth anyway, and it was a cool job to have, so it wasn’t that hard to work there. I didn’t excel at anything back then. It took me a while to figure out what it might mean to call myself an artist.

When did you come to grips with that and realize that you were an artist?

It took a long time.

I would see your stuff back in New York when I was a kid and I dug your work.

Do you remember what year?

I went to New York in ’82 and really hung out there. Then I started going back and forth from there all the time.

That was when I was just beginning.

I remember seeing this one piece, and I don’t remember what year, but it was the “Your Body Is A Battleground” piece.

Yep. That was in ’89.

I was in New York then and I remember seeing the split screen and the positive and the negative sides of it and the words. I was like, “Wow. That’s so true.” I could relate to that because I was a skateboarder my whole life.

That’s right.

I saw that and I was like, “This lady is definitely hitting something because my ankle hurts right now as I’m walking by.”

[laughs] Where are you from originally?

I’m from California, but I’ve spent time in SF and New York, and I also come from a punk rock background, which has a lot of punk rock attitude towards the man telling us what we should and shouldn’t do.

Right. Sure.

There was a part of me that could identify with the things that you were saying. My father did these adhesive decals and stickers back then when he worked for 3M and I always saw fonts and all sorts of different layouts and graphics, and my brother was an artist, and so I was hip to it. I liked your art and the simplicity of it and the message was powerful and bold. It had that “Wake the fuck up” message and approach to it that ended up changing my life.

Oh, come on. Oh wow. Thank you. Tell me. How old were you when you started skating?

I started skating in 1966 when I was six years old.

Yeah. Where was that?

I was up by Berkeley. Then we came down here to the LA area and we were surfers and skateboarders. I come from a background where I had a brother who is a truly gifted guy who could make anything from ceramics to film to photography to drawing, so it was in my face.

And how long has the magazine been around?

Juice Magazine has been around for 25 years now.

Yeah, because it looks great. It’s got a lot of visual activity.

Right. It seems as though the whole visual stimuli is way more prominent now than ever before, which is a good thing, and to add the message is really cool.

Some of my undergrads are skaters, especially around here, in So Cal, and the great thing about teaching at a university is that it’s not an art school. The undergrads are not just a bunch of cool art kids that already know what kind of careers they are going to have. At a public university, there are a lot of students that are the first generation of their household to go to college, and the first generation to speak English, and it’s a whole different thing. You really do feel that you can make a difference in their lives, and they don’t know who the F we are. I teach with terrific artists and a lot of the kids don’t know who we are and that’s better than having somebody blow smoke up your ass.

So you started to get recognized around ’81. Take me through how it happened.

It was so incremental. Because I didn’t go to college, I had no peer group, like Teen CalArts or Team UCLA or anything like that. I did meet some artists who became my friends in lower Manhattan who did come out of CalArts. It took a while and we would show our art, but we never expected to sell it. Then it did start selling. I remember I sold out my first few shows and I made $75 on each one. I paid to make the prints and I paid for the frames and paid for the mounting and then split the sales with the dealer. The work became known and that was amazing to me. It was unexpected and it did a lot for my self esteem, that’s for sure.

Oh right? You learned how to do layout and everything back then too, right?

Yeah. That’s what I did at magazines and that’s where I developed the skill set of working with pictures and words. I got that from working at magazines.

Did you have a studio to work out of?

I had a loft in New York, but I don’t have a studio now. I have a space like an office, and I have space for a studio, but I have never had an assistant.

It was always you only, but you have people helping you do the installations of your artwork, right?

Yeah. There were fabricators that are printers, and they do installations, like Coloredge, but I don’t have any assistants or people making me lunch or cleaning up my space. It’s my old New York roots and class awareness. More power to people that have that sort of posse. I just don’t need it.

Right. Well, you’re a one-woman show.

Yeah. There are a few women artists that I know that actually feel that way too.

Do you think that is from your upbringing?

Yes, very much.

You think you can contain everything and make sure it’s done properly too?

Well, I think that’s true. I also feel uncomfortable with accolades. I don’t need people to stroke my ego. I like to have a cooler relationship with people that’s not so hierarchical. I’m not a master or a great artist. I really dispute that kind of stuff, and my art has been fueled by that kind of questioning.

Right. How does that make you feel when they say, the master, Barbara Kruger?

Well, they don’t usually say, ‘the master’.

[Laughs] Well, you’ve been making art for a long time and you’re a pioneer and many consider you legendary.

Well, it’s thrilling to me. It is absolutely thrilling, but I always like to remind people that life is such a trip, and it’s always a combination of hard work and good luck and arbitrariness, and social circumstances. Thirty-five years ago, people couldn’t do work with type and pictures and call it art in quite the same way they do now. People make work on screens now. So many people are working digitally. It’s so different now.

Have you moved over to digital?

Well, my work is certainly made in different ways. When I first started doing work, they were paste-ups. Now I do stuff on digital files of course. Things are printed on digital files and I shoot video on digital files. It’s different.

So you’re a feminist, yes?

Well, yeah, I mean there are a million different ways to view that. I always like to think of it in plural, like there are feminisms. I always say that I’m an artist who is a woman and a feminist. I don’t make feminist art. I don’t know what that is. I don’t like categories. I don’t think about black art or feminist art or queer art or white male art. It’s just art. I definitely think that women call themselves feminists and that means different things to you according to what your color is and what your class is and what your gender is.

Right. It does sometimes seem like the male can be just a pig, especially now even more so with sexual harassment and the snowball effect of all of that going down.

Yeah. It’s just the beginning. Of course, I’m not shocked, and of course it’s going to get even more complicated than it is now. It’s centuries of a kind of behavior that is being exposed more now than ever. Again, things change. And I’m not a nostalgic person. I hate nostalgia. Whenever people start talking about the good old days, I don’t know any good old days. If you’re a woman or a person of color or a queer person or a sensitive white guy, there were no good old days. It wasn’t better. The only way it was better, was that there used to be more of a place for the working class and the working poor to live. Now there is a complete liquidation of the middle class and the working class. Having working class people think that Donald Trump has their best interests at heart, that’s very disappointing, but not a surprise.

Within that whole thing, like you said, it goes back centuries, when they used to club women and drag them by the hair. It’s like some crazy satire to the modern version of what’s going on now.

Well, hopefully, we’ll come to a time that women and people of color don’t have to be extraordinary to be considered ordinary because all of us have the capacity to be cruel. All of us have the capacity to abuse power, but the folks that have been in power the longest have more of a capacity to do that. What we’re seeing now is a slight crumbling away of that particular structure.

How do you decipher the difference between commercialism and art?

I don’t think there is a borderline. It’s very hard. I always tell students, “Don’t expect to sell your work right away.” Make your art as strong and as powerful as it can be. Whether there are art markets or art fairs or galleries or museums or not, the spark to make art, to make commentary, is going to be there whether something is bought or sold or not. The blurry lines are more so now, because there is a small number of very rich people who invest in art as speculation now. There are fewer collectors and more speculators and that’s how things have changed too.

Selling art has become as important as selling real estate. It’s like a commodity.

Art is now flipped in the same way too. It’s huge. It’s just the way markets work. Very few artists are lucky enough to complain about being flipped, so let’s get real about that. I have been very fortunate, but I make work about that kind of thing. My work is about the cruelties and pleasures of being alive and having or not having money and being seen or being invisible. I try to make my work about that stuff.

Where do you draw your influences from?

Every day, like right now, I have three screens going, and I have a window. You look out in the world and you see what’s going on. One of my joys, but disappointments, is that some of the work that I’ve done 30 years ago feels as necessary today as it was then. And I don’t feel like I’m flattering myself. I wish that it wasn’t. It’s just that the state of the world still hangs on these issues of abuse and power and destruction.

You bring awareness through your art. Do you ever get disappointed by people’s reactions? You’re making it clear that this is what’s going on and it doesn’t change.

No. There are so many different kinds of work and some work is so deeply coded within an art world, and some work flows within the world like mine does because it’s a reflection of how I grew up. In this country, and in Europe and Asia too, most people don’t know the name of an artist. They don’t know who the visual artists are. Most people know Andy Warhol, but if people think that people know the name of visual artists, they’re wrong. They live in a bubble or in the art worlds or Chelsea or certain parts of LA and London. The visual arts are totally marginalized in this country. The only time people think about them is when they hear about the crazy secondary auction prices or some kind of scandal or censorship. Basically, there hasn’t been any government funding for the arts in 40 or 50 years, and considering what the government is now, it’s just as well, because they would want to put you in jail for it anyway.

Does that not drive you crazy, that this beautiful outlet of communication is not so well received in the United States? I mean if you go to Riverside, California, no one is really going to tell you what artists there are.

You can walk down the streets of Los Angeles and it’s the exact same thing. People are deluded if they think that it’s any different than that. As an artist, one does what one can. You continue to make your work, and you might reach some people, maybe not. Delusion doesn’t help unless you’re Donald Trump. He’s such a good salesman and people are naive. I always say it’s nice to know who’s F-ing you when you’re being F-ed. Hopefully, some of us, as artists, are doing work to remind you who is F-ing you.

Let me ask you about what your work regiment is like.

It’s very different all the time. There’s no separation. I get up and turn on my devices and get something to eat and work. This is a light quarter for me with eight hours a week of undergraduate and five hours a week of graduate. That’s a lot of driving back and forth. I was at the grad studios late last night. Every quarter is different. I recently did a gallery show in Berlin too. I do very few gallery shows, but I felt very good about that installation. You should check it out online. Then Performa was a huge thing to do too and they were great to work with.

What about Performa? How do you relate to that and everything involved with it?

Well, I’ve known Roselee Goldberg, who created Performa, for many years. She used to run the Kitchen in New York. I think it’s a terrific event. Artists who work performatively, who don’t make objects, it’s even more difficult to sustain yourself. Performa, which itself doesn’t have a lot of money, but is incredibly ambitious, has to raise money to have all these artists do this work every few years, so I was happy to be involved with it. I don’t do too many gallery shows and it was a great opportunity for me to engage the streets and the billboards and the skatepark and the subways. I really wanted to do that because it’s an extension of the work that I’ve been doing for decades. I’m thrilled with how it worked out.

What is your goal when you go into a project like Performa?

It’s just to reach people with ideas and to promote doubt. I always say belief + doubt = sanity. Think about how we’re driven by consumption and desire and by the objects that we own or want. It’s stuff like that. Think about the subway art like, “Whose values? Whose justice? Whose hopes? Whose fears?” It’s pretty obvious. You don’t need a PHD in conceptual art to understand that.

No. I’m just curious what drives you and what satisfaction you derive from it.

It’s just to try to have a voice and meet other voices. It’s perpetually frustrating when our government and our justice system now is being taken over irrevocably. It will be generations to get back what we had. So many people don’t even vote or they vote their conscience and I can’t stand that because the world is bigger than their narcissistic conscience. We should have seen this coming and that we’d get a Supreme Court that will be abusive and punishing now because you had to vote your conscience. I’m not talking about any particular candidate, but a lot of the people that are complaining about the shit that’s going down now, should have thought about that, like the people in Michigan and Wisconsin and Illinois that voted their conscience and voted for Jill Stein who is like a Trump troll or Gary Johnson who didn’t even know the names of leaders of any foreign countries. I’m not saying fly the Clinton flag by any means, but you realize how power flows, and those votes brought us Donald Trump. About 77,000 votes in Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin brought us Donald Trump and what we’re living through now. Again, I’m not waving a flag for any candidate. I have plenty of problems when it comes to the Democratic party, but when it comes to the Supreme Court and judgeships throughout the country, if you’re a sensitive white guy or a woman or a person of color, you know your life is going to suffer because of this.

How do we get out of that?

I don’t know. It’s going to take a while now. The same thing is probably going to happen in the next election too and we’ll get another person on the right because the people on the left are going to be too pure to be spoiled by the hack ideology of what they see as a failed Democratic party. We’re going to have a split on the left, just like there is a split on the right, but the right will prevail. I can see it happening because young kids are very idealistic and naive and it’s almost like they don’t know that a judge appointment is a lifetime appointment. So those laws cutting down civil rights and cutting down voting rights and cutting down the rights around one’s body and cutting down health care, they are going to be feeling that long after you and I are gone.

How do you keep your sanity through all of this?

It’s because that’s what the world is and I’m not shocked by any of it. I’m pissed, but I’m not shocked.

Well, this has been happening for a long time. Maybe not to this degree, but it’s been going on forever, right?

Yes. Sixty-five years ago people were being put into ovens in a place where I just had a big show in Berlin. There’s been death and destruction and war and fear of difference for centuries, but it gets acted out in different ways in different times. I think that’s a good place to call it a day. It was great talking to you. I’m glad you reached out to me because the magazine is one of renown in the subcultures and I feel great about this.

It’s all good. You are who you are and, for me, that’s cool.

Hopefully, we can all continue. I’m one of these folks that wishes they could live forever with a minimum amount of pain.

When you figure that one out, please let me know.

I will. Steve, it was great talking. Thank you.

Thank you. Take care of yourself.

I will. Bye bye.

SHARE THIS POST:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)