ANDY KESSLER

interview and introduction by STEVE OLSON

As some say, and whoever they are,

the history of skateboarding has no place in skateboarding.

Well, just to correct you, it does, and like most history,

they never seem to learn from its history.

Imagine that. Enough of that history.

Now for a history lesson of

New York skateboarding’s godfather, Andy Kessler.

When it wasn’t the trendiest of trends,

And maybe a handful of cats were riding the streets of New York, Andy Kessler was right in the middle of the pack.

If New York seems wild now, you should have been

there then. You have no idea how wild, wild is.

But that’s history, isn’t it?

Now for something completely different.

Andy Kessler is still riding the same streets that were vacant then, but not now, and I don’t mean the lack of cars or people.

I mean the lack of skateboarders, and very few as mentioned

above. Take it from someone that knows, cares and still tries and makes things happen for the better of skateboarding

in and around the city of Manhattan. Read on, and learn

something that you thought didn’t matter.

Kessler.

What’s up? What are you doing over there on the West Coast?

Loving it. Let’s do this interview.

How are you going to do this?

[Laughs] We’re recording everything you say. I’m going to ask you some questions and that’s that.

[Laughs] Is it over?

Say, “Thank you.”

Thanks.

[Laughs] My first question of the day is, what is your name?

Andrew David Kessler.

Where did you grow up?

New York City.

In Manhattan?

[Laughs] I grew up in Manhattan. It wasn’t very exciting.

[Laughs] That’s one of the most boring places I’ve ever been in my life. There’s no action there. How do you stand to be in such a boring place?

It’s amazing that I’m still alive.

[Laughs] How are you still here?

I have no idea. I’ve been trying to kill myself for years. You witnessed one of my attempts.

You were lying in the bowl and we were yelling, “Get up. You can move.”

You said, “We can fix that. We can put it back into place. Just pull on his leg.” I think I said, “Don’t fucking touch me!”

[Laughs] Could you imagine that?

I’m just really glad that you guys didn’t touch me. I was happy to be left alone.

We’ll talk about that later. You grew up in Manhattan. When did you start skateboarding?

The first time I saw a skateboard was in the ‘60s, during the first explosion of skateboarding all over the country. My dad and mom would take me to the playground and I saw these kids on skateboards going down this hill beside the playground. I must have been five or six then. The older kids let me ride their boards down the hill. I could only ride on my butt back then. When I was ten, I’d found my first board in the basement of our building. It’s been all downhill from that point.

Literally.

Me and one other kid, Mark Danzig, shared that skateboard that I found in my basement. One of us would ride our bike with a rope attached to the sissy bar and we’d tow each other around the park.

What park?

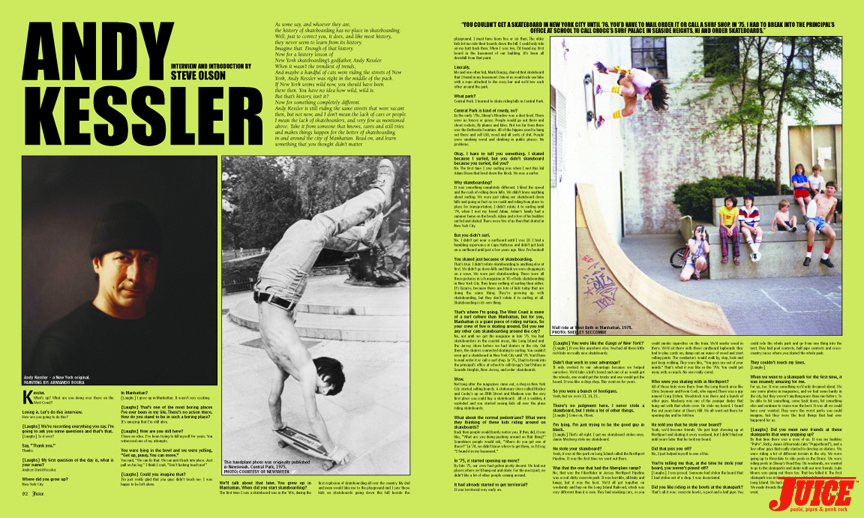

Central Park. I learned to skate riding hills in Central Park.

Central Park is kind of rowdy, no?

In the early ‘70s, Sheep’s Meadow was a dust bowl. There were no fences or grass. People would go out there and shoot rockets, fly planes and kites. Not too far from there was the Bethesda Fountain. All of the hippies used to hang out there and sell LSD, weed and all sorts of shit. People were smoking weed and drinking in public places. No problems.

Okay. I have to tell you something. I skated because I surfed, but you didn’t skateboard because you surfed, did you?

No. The first time I saw surfing was when I met this kid Adam Dison that lived down the block. He was a surfer.

Why skateboarding?

It was something completely different. I liked the speed and the rush of rolling down hills. We didn’t know anything about surfing. We were just riding our skateboard down hills and going as fast as we could and riding from place to place for transportation. I didn’t relate it to surfing until ‘74, when I met my friend Adam. Adam’s family had a summer home on the beach. Adam and a few of his buddies surfed and skated. There were five of us then that skated in New York City.

But you didn’t surf.

No. I didn’t get near a surfboard until I was 18. I had a humbling experience in Cape Hatteras and didn’t get back on a surfboard until just a few years ago. Now I’m hooked!

You skated just because of skateboarding.

That’s true. I didn’t relate skateboarding to anything else at first. We didn’t go down hills and think we were dropping in on a wave. We were just skateboarding. There were all these pictures in Life magazine in ‘65 of kids skateboarding in New York City. They knew nothing of surfing then either. It’s bizarre, because there are lots of kids today that are doing the same thing. They’re growing up with skateboarding, but they don’t relate it to surfing at all. Skateboarding is its own thing.

That’s where I’m going. The West Coast is more of a surf culture than Manhattan, but for you, Manhattan is a giant piece of riding surface. So your crew of five is skating around. Did you see any other cats skateboarding around the city?

No, not until we got the magazine in late ‘75. You had skateboarders in the coastal areas, like Long Island and the Jersey shore before we had skaters in the city. Out there, the skaters connected skating to surfing. You couldn’t even get a skateboard in New York City until ‘76. You’d have to mail order it or call a surf shop. In ‘75, I had to break into the principal’s office at school to call Grogg’s Surf Palace in Seaside Heights, New Jersey, and order skateboards.

Wow.

Not long after the magazines came out, a shop in New York City started selling boards. A stationary store called Blacker and Cooby’s up on 88th Street and Madison was the very first place you could buy a skateboard. All of a sudden, it exploded and you started seeing kids all over the place riding skateboards.

What about the normal pedestrians? What were they thinking of these kids riding around on skateboards?

Back then people would barely notice you. If they did, it was like, “What are you doing pushing around on that thing?” Sometimes people would ask, “Where do you get one of those?” In ‘74, we didn’t know where to get them, so I’d say, “I found it in my basement.”

In ‘75, it started opening up more?

By late ‘75, our crew had gotten pretty decent. We had our places where we’d hang out and skate. For the most part, we didn’t like a lot of other people coming around.

It had already started to get territorial?

It was territorial very early on.

[Laughs] You were like the Gangs of New York?

[Laughs] It was like anywhere else. You had all these little rich kids on really nice skateboards.

Didn’t that work to your advantage?

It only worked to our advantage because we helped ourselves. We’d take a kid’s board and one of us would get the wheels, one would get the trucks and one would get the board. It was like a chop shop. This went on for years.

So you were a bunch of hooligans.

Yeah, but we were 13, 14, 15…

There’s no judgment here. I never stole a skateboard, but I stole a lot of other things.

[Laughs] Come on, Olson.

I’m lying. I’m just trying to be the good guy in black.

[Laughs] That’s all right. I got my skateboard stolen once. Jamie Mosberg stole my skateboard.

He stole your skateboard?

Yeah, it was at this park on Long Island called the Northport Pipeline. It was the first time we went out there.

Was that the one that had the fiberglass ramp?

No, that was the FiberRider in Jersey. Northport Pipeline was a real shitty concrete park. It was horrible, all kinky and lumpy, but it was the best. We’d all get together on weekends and hop on the Long Island Railroad, which was very different than it is now. They had smoking cars, so you could smoke cigarettes on the train. We’d smoke weed in there. We’d sit there with these cardboard lapboards they had to play cards on, dump out an ounce of weed and start rolling joints. The conductors would walk by, stop, look and just keep walking. They were like, “You guys are out of your minds.” That’s what it was like in the ‘70s. You could get away with so much. No one really cared.

Who were you skating with in Northport?

All of these kids were there from the Long Beach area like Chris Seymour and Kevin Cook, who ripped. There was a guy named Craig Etchen. Woodstock was there and a bunch of other guys. Mosberg was one of the younger dudes that hung out with that whole crew. He stole my board. I found this out years later at Cherry Hill. We all went out there for opening day and he told me.

He told you that he stole your board?

Yeah, we’d become friends. We just kept showing up at Northport and skating it every weekend, but I didn’t find out until years later that he took my board.

Did that piss you off?

No, I just helped myself to one of his.

You’re telling me that, at the time he stole your board, you weren’t pissed off?

[Laughs] I was pissed. Someone had stolen the board that I had stolen out of a shop. I was devastated.

Did you like riding in the bowls at the skatepark?

That’s all it was: concrete bowls, a pool and a half pipe. You could ride the whole park and go from one thing into the next. They had pool contests, half pipe contests and cross-country races where you skated the whole park.

They couldn’t touch my lines.

[Laughs]

When we went to a skatepark for the first time, it was insanely amazing for me.

For us, too. It was something we’d only dreamed about. We saw some photos in magazines, and we had some banks in the city, but they weren’t anything more than one hitters. To be able to hit something, come back down, hit something else and continue to cruise was the best. It was all we could have ever wanted. They were the worst parks you could imagine, but they were the best things that had ever happened for us.

[Laughs] Did you meet new friends at these skateparks that were popping up?

By that time there was a crew of us. It was my buddies “PaPo”, Ricky, Jamie Affournado (aka “Puppethead”), and a few other guys that really started to develop as skaters. We were riding a lot of different terrain in the city. We were going up to Riverdale to ride pools in the Bronx. We were riding pools in Sheep’s Head Bay. On weekends, we wanted to go to the skateparks and skate with our new friends. Luke Moore was going out there too. That boy killed it. The first skatepark was in Huntington, Long Island, then Farmingdale, Long Island. We had a fun indoor park out on Staten Island. We made friends that we liked to skate with everywhere we went.

Did those cats inspire you?

Absolutely. It brought more energy to the whole experience. We had our crew and it multiplied from three to six to ten, and then the energy of the session was so much greater. It was good times…

If you weren’t skateboarding, you may never have met those people.

That’s right. I’ve met my best friends skating.

There’s also the element of weather on the East Coast. It’s colder. You have seasons. It’s raining and it’s snowing. It just seems like it’s a more hardcore element.

[Laughs] Well, that’s something that you might want to bring up with Jim Murphy. He’d tell you that the East Coast is way more hardcore than California, and that you guys are a bunch of sissies out your way.

[Laughs] Great. Goodbye. I’m trying to give you some props and you come back with that?

[Laughs]

[Laughs] Unbelievable.

[Laughs] That’s okay.

No, but if you’re into skating on the East Coast, it could be five degrees and snowing outside, right?

Yeah, but when we were kids, it didn’t matter. We were skating in zero degree temperatures. If there were snow on the ground, we’d clear a path and skate our ramps in Riverside Park. We’d skate them year-round. We’d skate the pools up in Riverdale year-round. It didn’t matter. We’d still ride all year-round.

Were there a lot of pools in Riverdale?

From early ‘77 through late ‘78, Riverdale was happening, but it only lasted a couple of years.

How was the whole scene when Cherry Hill opened up?

It was sick, but it was two hours away from New York City. None of us had cars. As easy as it was for us to hop on a train and get to Long Island, it was much more complicated to get out to Cherry Hill, NJ. I only made it there a handful of times. I got to see you skate there.

Why did you have to bring that shit up?

[Laughs] Bad memories?

[Laughs] No.

I thought it was great. I got to see just about everyone skate there. I saw you, Shogo, TA, Jay, Stacy, the Haut team and the Sims team. There were a bunch of those guys that ripped.

Kevin Reed ripped. Eric Halverson ripped.

When I saw you there, you were with Brad Bowman and Doug de Montmerencey. Those guys were killing it. They were snaking you all over the place that day.

[Laughs] That’s true because I was on Quaaludes that day.

[Laughs] Fuck. Here you go. This one’s for you. Those guys were rolling in the egg bowl and you were like, “Fuck this.” You went over the half pipe and rolled in. I saw the run you took and it’s still etched in my mind. It was badass. It was different from the way I’d seen anyone else skate that half pipe.

That’s okay.

It was cool.

I was still on Quaaludes.

[Laughs] I was trying to give you some props.

That’s fine, but I don’t want any props. I just want pills.

[Laughs]

Skateboarding still wasn’t banging in Manhattan, but you guys were still going.

Well, that park opened up in 1978, so, no, it wasn’t banging in Manhattan yet. After the explosion in ‘75, most of those kids stopped skateboarding, but there were a bunch of us that just kept going. That’s how it’s been over the years. You’ve seen it. Back in ‘75, the majority of skateboarders were kooks. There were only a handful of guys in New York that were hardcore and kept skating. You still see the same thing. With every new generation, there’s a ton of new skaters and then a few years later, it dwindles down.

Now New York is happening. The kids truly dig skateboarding and Manhattan is a great place to go skateboarding.

It’s a great place to roll around, for sure.

It’s my favorite place to have my skateboard. I’d much rather have my skateboard in Manhattan than anything else.

You can push down the streets through traffic, red lights and pedestrians. I don’t know of anywhere else in the world that has the same surroundings and energy as New York City. Sometimes ripping through the streets is the best thing you can do on your skateboard. There’s something really freeing about it. It makes you feel different from the rest of the world. You get a unique view on things.

Also, when you’re on your skateboard in New York, you’re in the streets. You’re part of the deal. You’re a part of everything that’s going on.

That’s true. It’s one of the most bizarre things to me now. I’ll be skating down the street and come to an intersection and…

Someone will ask you for your autograph…

[Laughs]

[Laughs] Go on.

When I come to an intersection, most of the time, I’ll see another skater coming in the opposite direction. Then I’ll skate a few more blocks and see another skater. It’s insane the amount of skateboarders that are riding the streets in New York City now. I’ve seen it go from no skateboards to almost everyone is riding a skateboard.

Did you ever venture out to the West Coast?

When I was 13 years old, I wanted to go to California and be a pro skateboarder, but I didn’t make it to California until I was 35.

[Laughs] I love that. What is wrong with you?

I’m just a retard.

[Laughs] I’m kidding. How was it going from clay wheels to urethane?

It was a whole other world, but it wasn’t the same experience here that you hear everyone in California talking about like, “It allowed us to throw harder turns or go up walls.” We didn’t have the type of terrain the West Coast had back then. It just made the ride so much smoother. You didn’t hit a pebble and go flying. It was still loose ball bearing wheels, so your bearings would still spill out, but it wasn’t long before precision bearings came along.

Loose ball bearings were a nightmare. You had to have some knowledge of maintenance.

Those were some of the best times I can remember.

How sick would it be to bring back loose ball bearing wheels? Were they faster?

I’m not sure. Were they?

Precision bearings made it easier to roll by and steal someone’s purse, silent-like.

[Laughs]

When was the first time you saw Skateboarder magazine?

1975.

Did that get you excited about the whole deal?

When the magazines came out, we were all stoked. I’d never seen anything like that. I didn’t know you could do all those things on skateboards. For us, that’s what we wanted to do. We never saw anyone ride up the wall of a pool. We just saw it in the magazines, tried it and busted our ass until we could do it. We figured it out on our own, not from videos. In some kind of weird way, we developed our own style. I’m sure it was the same with other skaters all over the country.

When you were a kid, did you think you’d be skating now?

I couldn’t think past being 16 years old. I sometimes think about it now. When I was 16, everything was right in front of me. By the time I was 25, I already had a lot of crazy shit behind me. You turn 30 and you can’t believe you’re 30. When you turn 40, you’re like, “How did that happen?” Now I’m 48. I never thought I’d still be skating. It’s been something that I’ve loved since I was 13 years old and still love today.

Do you still get the same gratification and sensation from it as you did when you were a kid?

I still get that. It depends on who I’m skating with and where. You never know where or when it’s going to hit you.

That session I had with you and Jumonji was insane. I don’t know what it was, but I had such an amazing time. I could have died and been completely satisfied with life. I had an amazing time and I just want to thank you for being alive. Now I have to go kill myself.

[Laughs] You’re one of the few people I really like skating with, and I always have a good time skating with Jumonji. There are just a few people that bring it together for me. Then there are the times when I’m skating through the streets by myself and I’ll flash back to how it felt when I was 13. I’m pushing down the street, weaving in and out of traffic and there’s nothing better.

Do people that do other activities have these same experiences? I don’t think so. They don’t get to return to that point of amazing sensation. I feel totally grateful that you get that in skateboarding.

I’m so grateful and stoked for that, too. You saw me fall that day in the bowl on Crosby Street. There was a moment, when I was in the hospital and thought, “If I never skate again, I’ll be all right.” Later, I realized it was just the drugs talking.

[Laughs] More drugs.

I’m so glad that I can skate now. I have so much fun. It doesn’t matter that I don’t skate the same way I skated when I was 16. In some ways, I feel like I skate better now.

What about how you don’t have the pressure of having to prove yourself? You can really tune in to what it’s really about.

Maybe. At the same time, I was really competitive. There were days that I’d go to Central Park early, at like six in the morning, and skate because I really just wanted to be good. I wanted to be the best. There was a time when I really loved competition, too.

Okay, let’s go back. You’re skateboarding all over Manhattan and it’s obvious that you’re a truly dedicated dude. You’re subjected to so many wild, crazy things that are going on. Did that get you into shit that maybe you wouldn’t have gotten into if you weren’t on a skateboard?

It might have, yeah. There were cats that I hung out with that were really hardcore skaters and then there were cats that were pretty good. Those cats were a little older than me and they were into all sorts of other things. That’s the group I started hanging out with. They all sold weed and acid and dabbled with other types of drugs. Eventually, most of them got into other hardcore drugs. A lot of them died. A lot of them went to jail. I got into a lot of that shit, too, at a pretty young age. It’s another one of those experiences that I feel lucky I got out of alive. I was either going to jail or someone was going to kill me for doing some stupid shit.

But you managed to pull through that.

I got real lucky. I thought I’d lost my family because I’d been out of the house for a while. They had court orders of protection against me because, the way I saw it, everything that was in the house that wasn’t nailed down was for sale, so they couldn’t have me around.

Do you think those choices interfered with your skateboarding?

Yeah, I do. I couldn’t hang on to a skateboard. I’d get a skateboard and sell it for a hit. Then I’d get another board and sell it. I skated through that whole period, but less and less. Those were the years between ‘82 and ‘86.

I didn’t meet you until much later, but I was in New York skating and I didn’t see many other people skating. There were a couple of dudes like Ian and Harry. Then I skated that ramp at the night club area with “Puppet” and Henderson.

I missed that. Those guys wouldn’t call me back then. That’s when I was bottoming out on dope and crack or just getting cleaned up. During that time, none of those dudes would call me. I was out of my mind.

Well, I’m glad you made it. You’re one of the longest standing skaters that still ride in Manhattan.

[Laughs] That’s about the only thing I’ve still got going for me. Tha and $2.50 and I can get on the subway.

Okay, settle down. I know you can’t take that to the bank either.

[Laughs] That’s for sure.

After your drug phase, when did you pick back up your skateboarding trip?

In ‘86, I could hold onto a skateboard again. At least I wasn’t selling it. At that time, I still wasn’t hanging out that much with Pup and Henderson and that whole crowd. I think my drug period really separated us all quite a bit, so it took some time to bring us back together. By the late ‘80s, we were going to different parks and ramps.

When was the first time you skated the Brooklyn Banks?

That was in ‘83 or ‘84, pre-Future Primitive. We rode it a handful of times before there were videos. I didn’t think they were all that great back then. When I started finding out that guys were going there every day, I asked myself, “Why?” It’s good for a couple of laughs and then it’s time to go. I couldn’t see hanging out there all day.

Which was the best of all the generations of skateboarders to come through New York City?

My boys were the best. It’s best when you’re young. Those were the days.

It seems like it’s better now, though.

There is a community of skaters today that are dedicated to skateboarding in New York, which is a good thing. Maybe today is better. Maybe these are the good ol’ days.

Can you say that again?

It’s better than it’s ever been, in some ways.

But now it’s trendier than ever.

Yeah. A skateboard is the most popular accessory in New York. Chicks have accessories.

[Laughs] It all depends on how you accessorize, baby. Those shoes really don’t go with that dress you’re wearing. Okay. Let’s talk about some things that piss you off.

Okay. When a group of people claim something as their own when they weren’t really a part of it and they start making money from it – that pisses me off.

Be more specific.

It’s about the Zoo York trip. They stole our name. The crew that I skated with in the ‘70s was “Zoo York.” The guys that started the company were in diapers when we were skating pools. They were never part of our crew. They made money off our name and they never gave anything back to any of the original dudes. That pisses me off.

It doesn’t sound like you’re that pissed.

[Laughs] I’ve had a lot of time to review.

I totally understand what you’re talking about.

If it had happened to anyone else, I don’t know if they’d shake it off that easily. It was part of who we were as skaters in New York City in the ‘70s. I don’t want to sound like I’m full of hate for those guys, because I’m really not, but they didn’t really do the right thing.

Maybe I can help you on this. They don’t show any respect.

None.

You know what? If you show me no respect, you get the truth.

There you go.

Not to quote A Few Good Men, but a lot of people “can’t handle the truth.” The truth is something they have no part of. You’re just calling them out on their stunts.

When those cats look at me as being bitter, fuck them. If they had it done to them, they would feel the same way.

We hear nothing but whining from them.

[Laughs]

I understand it. In this day and age, whether people dig it or want to accept it or acknowledge it, we’re almost 50 years old and we’re still skateboarding and fucking up the boundaries because we came from where we came from. They can say whatever they want, but they will never have the dedication and passion that we do because that comes from our soul and they’re just a bunch of soulless kooks.

[Laughs] That’s why I love you, Olson. I really do.

I could just be in my own little world, but I have a connection with you because of that.

It’s not always about the money. I’m not making any money off of skating and I’m still doing it.

Do you make your own skateboards?

I’ve been making them for friends and selling them here and there. I spray-paint them and make each one unique. I put a little bit of myself into every one.

You’ve built some shit to skate around New York City.

Yeah, I’ve been fortunate enough to be a part of that. I’ve built some ramps and bowls. I’ve been lucky to be at the right place at the right time to make some things happen. That’s been a real learning process for me, too. It’s been some of the best experiences, too. It’s like that park in Riverside. The making of that park was a beautiful thing.

How did it go down?

It was a project that was put together through Riverside Park, their administrator and an educational center called the Salvadori Institute. They got 20 kids together, and, over a six-week period, we took these kids to a skatepark in PA. Then we brought them up to City College over two weekends where they got to do drawings and clay models for the park. Then they met with engineers and surveyed the park, which was a derelict playground at the time. The parents wouldn’t even bring their kids to the playground because it was full of crack addicts. Then we took the kids to this retreat for conflict resolution. I got to be a part of all this with them. Then we built a half pipe and a bank in six weeks at the park. And the kids got paid to work all summer building it too. It all started with an idea. The administrators had the foresight to put it together. At the time, I had a little bit of money and wanted to build a ramp somewhere in New York, but I was getting shut down all over the place. I finally got a hold of the administrator’s office in Riverside Park, but the assistant administrator shut me down. Then the administrator called me a few weeks later and said, “I have an idea.” He put the whole thing together and we turned that derelict playground into a skatepark. It’s still going on. The crazy thing is, that area is where we used to build our ramps in the ‘70s, so it’s come full circle. It’s a beautiful, landmark park in New York City, right on the Hudson River. It’s also very close to a graffiti wall in New York that all my friends used to write on. It was the Soul Artists Wall, the hear of Zoo York. That’s the wall where they did the Wildstyle piece, right there at 108th Street.

That’s dope. So through your whole deal of living in Manhattan, you saw the graffiti thing, the punk rock thing, the skate trip and the rap trip.

I was immersed in skateboarding. As for the graffiti thing, everyone I knew growing up wrote graffiti.

Why did you write graffiti?

It was about establishing yourself, just like skateboarding was. Everyone had a tag (name). My boy SE-3, later on, became Haze. There was WAR-1, SIE-1, LSD-3, Revolt and Zephyr. There were all these cool names. You wanted a name for yourself. I wrote AK1 back in ‘73, which was early. My buddy Chris started to write Bang 137, so I started to write Fang 171. Later, I got the name KESS. We were trying to make a name for ourselves, literally. That’s what graffiti was about.

Were those graffiti guys that you mentioned in the original Zoo York crew?

Some of them were. The guys in the original Zoo York crew were PaPo whose real name is Catalino Capiello and Ricky Mujica. Those were my boys. Those are the guys I consider Zoo York. They were the guys I wanted to skate with every day. My friend Marc Edmunds wrote Ali and started Soul Artists in ‘73. He’s the guy that coined the phrase “Zoo York” in ‘76. There’s a myth that Zoo York was a graffiti crew, but it wasn’t. It was just a reference to New York City. In ‘79, Marc started to regroup the Soul Artists to put out a ‘zine called Zoo York Magazine. They did one issue, and it had a fake contest story about us taking on another crew. It was funny. The ‘zine covered everything from politics and sports to community. He had his trippy art in there. Marc died in ‘95 from drug-related problems. He was in Arizona when he died. There are a bunch of guys here in New York who know the real deal, and there are a bunch of guys that came later that don’t, and don’t really give a shit. If you know, you know. If you don’t, you don’t. I know. I was there.

That always happens, though. Let me ask you this. Do you think skateboarding gave you a life? Through your skateboard and your passion for it, do you think that turned you on to other things that might not have happened?

I’ve met some incredible people and been a part of some things that I never thought would happen. It’s brought me to different places, so I’ve been able to travel. It’s given me some memorable experiences. There was a time when I was just happy skateboarding, without all of the grandiose crap. I was just working for a living and skating. But to answer the question: yes. Skateboarding has given me a life and being clean has helped me to enjoy it.

Why do you still skateboard?

From time to time, it still turns me on.

You turn me on.

[Laughs] Okay, Olson.

[Laughs] My bad. You were just starting to sound sexy over there.

[Laughs] Stop right there.

So we’re skating that bowl down there on Crosby Street and having a blast when you took that slam. You slammed from the top onto your hip and your knee. I told you to stay off your knees and you didn’t listen.

[Laughs]

So what happened?

Well, I had a bad knee to begin with, but I knew something was wrong when I couldn’t move my leg. It turned out that I dislocated my femur and broke my kneecap from the impact. The dislocation broke the socket part of my pelvis. When they got me to the hospital, they thought it was really bad news. The doctors said, “How did you break your pelvis like that?” I said, “Skateboarding” They said, “This is the kind of injury you’d normally see in a head-on car crash.”

We were over there trying to pop it back in.

I remember that.

You were lying there, yelling, “I’m so cold. ” I felt so bad for you. There was a part of me that wanted to get into water sports at that moment.

[Laughs]

I’m just kidding. Your recovery time blew my mind. You were skating six months later.

I was in the hospital for a week. I was on crutches for three months. I was surfing eleven days before I was supposed to get off my crutches. I was skating again a month or two after that. By six months later, I was really starting to skate again. Now I feel like I’m back to where I was before. It’s incredible. People still ask me when they see me, “How’s your hip?” And then I go for a grind. I had a lot of help from a lot of people, which got me through it all. I will be saying thank you for the rest of my life.

I think you skateboard because you’re passionate about it and you really dig it. That’s really inspiring to me. When I come to New York, I can’t wait to meet up with you and just roll.

Thanks, Steve.

So what’s in your future?

Right now, I have a little gig doing some construction. I’m going to save some money and go on a surf trip.

Will you ever come to California to visit us?

No, I don’t think so.

[Laughs] Well, that’s great, because we don’t want you here anyway. We have the bitter patrol covered here.

[Laughs]

You should come and visit. You have a place to stay. It’s “go time”.

I’ll be out there soon enough. Maybe I’ll drive out there and make you drive down to Mexico with me for a surf trip.

I’m coming to New York soon, so I’m going to kidnap you and make you drive back with me.

Do that.

This was excellent. I’m stoked that you’re around. That’s the way it is.

Thanks, Olson.

R.I.P. ANDY KESSLER.

June 11, 1961- August 10, 2009

ORDER ISSUE #66 BY CLICKING HERE…

SHARE THIS POST:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

One Response