STACY PERALTA

INTRODUCTION AND INTERVIEW BY STEVE OLSON. PHOTOS BY C.R. STECYK III, J. GRANT BRITTAIN, JIM GOODRICH AND DAN LEVY.

“You’ll never amount to anything” ???

‘Wait a minute, I’m just a kid’…

Surfers and skaters from the early ‘70s,

That’s what most heard, except a few…

One, which didn’t listen so closely…

is this guy, Stacy, Peralta that is…

from one talent to the next, it all depends

on your focus, and commitment…

If you don’t know who I’m talking about, you will.

Peralta has played a lot different roles…

from Skater to Director, as they say…

the guy has got talent, that’s obvious…

Do I say more? That’d be a bore…

Read on, it’s all in Black & White…

Stacy.

Yes. Hello, Steven. [Laughs]

Hello. I’m glad you’re enthusiastic, Stacy.

I’m very enthusiastic about this. I’ve been waiting for it.

I want to talk to you about how life is as Stacy Peralta.

Okay. Check this out. Our skateboarding careers lasted pretty much three years. When I look back on that time, I think, “Our careers never even started. They were over before they even started.” When we were growing up, nobody skateboarded past the age of 21, so we didn’t think there would even be anything after 21. We didn’t realize that our best years might be from 20 to 30. Our careers ended in our early 20s. I think we finished before we even started. We were still kids. I mean look at the guys today. They’re skating really good even in their 30s. We were out so early. That’s a shock to me when I look back. At the time, we were the barometer for the future. There was nobody ahead of us.

Well, the word pioneer comes into play.

Yeah. Also what we had going against us is that we had to live through the skateboarding revolution. We had to live through wheels and boards and trucks changing under our feet constantly. We had to live through terrain changing under our feet constantly. We had terrible boards, terrible trucks, terrible wheels and terrible terrain, so we were developing at a really difficult, vulnerable time.

That’s true. We were in the developmental stages of skateboarding and learning how to take it to the next level in that evolution.

Exactly. We were doing all that while we were being undermined with all of this change. We had to constantly adapt to the terrain and the products while we were trying to learn all the advanced moves that hadn’t been invented yet.

Right. In the beginning, the skateboard was looked at as a toy.

Totally. At that time, you had to buy it at the toy store.

That’s how it was. I think it has advanced itself out of the toy thing now.

Yes. Now it’s whatever you choose it to be.

How was it for you when you first got on a skateboard?

I have been asked that question many times in my life and I never had an answer that seemed satisfactory so, about five years ago, I really had to think about what it was that originally got me and I finally remembered it. There was a drug store down the street from my house on Venice Boulevard and it had a double-wide sidewalk that went completely around the perimeter of the drugstore. It was that kind of cement that they poured back in the day that was just perfectly groomed with the slightest bit of sanding on the top of it. Remember concrete like that? It was just perfect. It had just a touch of sandpaper scrape on the top of it.

Yeah. It had a little traction.

It had a little bit of traction but, otherwise, it was just a perfect sheet of glass. We used to skate down there when we were little kids. Before I go on, I have to say something about bicycles because bikes were the only thing we had to hold up to skateboards back then. When you ride a bicycle, you’re sitting down on a seat. It’s passive. You’re holding on to handlebars and your feet are on pedals. A bicycle offers a form of security that a skateboard can’t. On a skateboard, you’re standing on top of something very small that is moving and you become the center of the balance. There’s nothing passive about it. In fact, it’s a very insecure experience. Anyway, I remember skating one day in front of the drug store. I was zooming around and I could feel the rumble of the sidewalk and the hard clay wheels coming up through my feet. I could feel the vibrations in my legs and the wind at my face and the whole time I was trying to find balance. I was leaning this way and that way, forward then a bit backward, and left then right. I kept shifting my weight to compensate for the changes in speed and the rock hard terrain and rock hard wheels. The entire time I was looking for equilibrium and trying to balance all of these forces. I was this seven-year-old kid in the middle of all this chaos. I was going down the sidewalk on this little board very fast with all this activity swirling around me. There were cars and people. There was the rumble of the sidewalk coming up through my feet and the terror of falling face first onto concrete and, all of a sudden, in the midst of all of this, I started to relax. Suddenly, I was feeling this sense of stillness within me. I found my equilibrium and I was totally at peace. I was totally still inside and I was flying down this sidewalk. Every time I get on a skateboard, I relax and I’m at peace within myself. That’s what attracted me to it. It was the search for that perfect glide when suddenly everything becomes quiet and everything becomes still.

Yeah. It’s its own little zone.

Exactly. I was seven years old, and I couldn’t articulate that. I only knew that’s what I was feeling. It wasn’t until years later that I figured out what it was. What about you? When did it happen for you?

When I was six years old, I got a board under the Christmas tree. It was like, “Look at this contraption with four wheels.” I was just lying down on it and feeling the speed and flying down the sidewalk. It had nothing to do with surfing. It had to do with the fact that I had an older brother. I was flying down the street and I would usually lay on my stomach, so I could brake with my hands. Then I learned how to stand up on it. That was the very beginning with my first skateboard.

I just found something out that I didn’t know when I had dinner with my mom last night. My mom is a really crafty person and she could make things. If I needed my bicycle repaired, I never went to my dad. I went to my mom because she could fix stuff. She figured stuff out. She told me last night that she made me a box scooter skateboard. She cut a pair of roller-skates in half and put them on a board and put the box as the handlebars on the board for me. I was four or five years old and I don’t even remember that. I remember we had one, but I didn’t realize that she made it. I didn’t know that she saw other kids doing it and decided to make it for me. I had no idea. I just found out.

She made a box pushcart skateboard?

Yeah. It was a skateboard scooter. I have a memory of riding one as a kid, but I didn’t realize that it came from her and I didn’t realize that she thought of it, like, “Hey, I’m going to make this.” That’s just the stuff that she would do. I remember one time I wanted to repaint my Schwinn bicycle and she helped me take it apart and hang it and paint it and do the whole deal. She was really good at stuff like that. If she and my dad ever had to fix something in the house, she would usually figure it out. She’s just good at figuring stuff out mechanically. Her dad was a tool maker, so she was really clever like that. Let me ask you this. When you look back on your skate career, are you satisfied with it or do you have regrets?

I can’t say I have regrets. It happened so fast. We were in and then it died.

Exactly. It happened so fast.

Also, there was a point where I got injured and everything was happening at that point. I think I was at the top of my game when I got injured. When I rolled my left ankle at Big Bob’s skate demo in Texas, that took me out for a good four or five months.

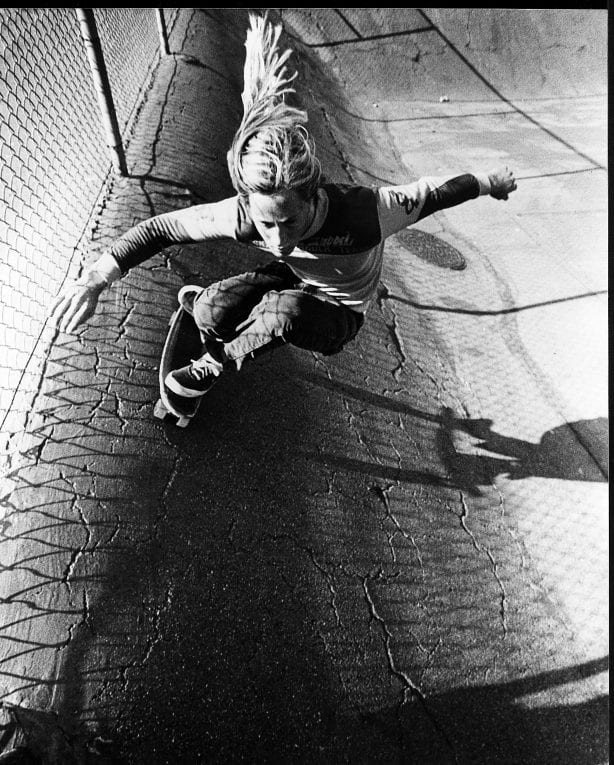

Wow. I remember the first time I saw you and I realized that you were going to be a really great skater. You and I were skating that Spring Valley park where Steve Cathey worked. It was me and you and Gregg Ayres and some other guys skating that pool at Spring Valley and I hated that pool. Nonetheless, we had to skate it to practice for the first Hester contest and I remember watching you and you had a really nice backside carve. You always hung at the top and you had beautiful control. I remember watching you and you were just going after it really methodically. You’d do it again and again and a little better each time. You were getting higher each time and you were always grinding the coping. You hit it with such accuracy and I was thinking, “This guy is good!” You were just coming on then and you were younger than us, so it was a bigger threat. We were like, “Wait a minute. He’s younger than us.” I had seen you around and I knew who you were, but that was the point where I looked at you and thought, “This guy is really good.” There was just an accuracy of how you skated, and I could see that you were really thinking like, “Oh, I have to do this better. I have to try this differently.” And then you’d take another run and do it better. That day stands out so vividly in my mind. The other memories I have of you were just the amazing competitor that you were. I remember you would come to the Hester contests and you wouldn’t practice. You never practiced. I don’t know if that was a psych you were laying on people, but you rarely showed what you had. As soon as the contest started, you were absolutely on fire. It was an amazing strategy and I gave that strategy to Tony Hawk years later when Tony came to me and said, “I want to stop competing. I’ve had it with competition.” He was just burned out and really bummed out because people were coming up to him and saying, “I know all I’m trying to do is get second place because I know you’re going to win.” He needed to take some time off and, when he came back, I urged him to go to contests and challenge himself by not showing anything to anybody. I said, “Just go in and take a couple of easy practice runs, but don’t show anybody anything. Run a psych on them. As soon as the contest starts, really give it to them and show them what they weren’t expecting.” I got that from you.

That’s nice. Thank you. Let me ask you this. Do you think it helped him?

I think it did because he came back stronger than ever. Do you remember not practicing a lot?

Yeah, but I think I had already practiced at those places.

Everybody had been there a week or two before, but there was something about you. You just hung back and didn’t show anything. I was like, “Wow.” It was really ballsy, because you were taking a huge chance and it could have failed. If you would have failed, it could have hurt you because it would have thrown you out. Instead, it had the opposite effect. When people saw you skating your routines, it was fresh, so it got them even more excited and it got the judges excited and they were more focused on you. You drew such good lines and that’s what the Hester series required. That’s why you did so damn well. The lines you drew at those pools won you most of those contests. You were putting in all your maneuvers and your style and you attacked.

Yeah, but before pool contests, there were freestyle routines, so lines were extremely important in connecting tricks and making it flow and look effortless. I’d see other cats doing that and I’d think, “Oh, that’s how it’s done in competition.” I think I translated that into pool riding.

Also there were a lot of people back then that did repetitive set-up kickturns into a trick. You would throw in a backside carve into a frontside carve into a frontside air and it seemed like you did fewer set up kickturns. You were really using a lot of the pool and trying to get in as much as you could in a short amount of time.

Maybe I was using my carve as my set up.

Carves are much more powerful than a kickturn, especially when you were grinding coping on it. You get so much more speed out of a carve and you keep your momentum moving.

The momentum will definitely keep going. If you were carving into something, it gave you that much more speed and possible power to go higher.

Let me ask you this question. When you tried to do your company SOS and it wasn’t working and you decided to go into something else like selling bonds, was it hard for you to make that transition?

That’s when skateboarding died and I was selling futures and commodities.

When you did that, was that a hard thing for you, identity-wise, to do?

No, because there was no identity left in skateboarding really. What did you do after your competitive skateboarding?

I started a business with George [Powell] because that was the only way I could stay in skateboarding. I couldn’t make a living as a pro skater, but I could make a living if I was working as a pro skater at a company that I was part of.

What year did you hook up with George and start Powell Peralta?

It was mid-1979. We were still tailing on the boom. It didn’t really end until the beginning of ‘81, so we had about a year to get established. I was making about $6,000 a month through Gordon & Smith and, when I started with George, I was only making $1,000 a month. It was literally just enough to pay my bills. I made $1,000 a month for the next five years. With that amount of money, I could pay all my bills and I didn’t have to get a job as a bartender or something.

How was that to go from getting paid pretty well for skateboarding to just having to scrape by?

I didn’t mind it at all because I had so much fun starting the company. It was such a fun thing conceiving ads with Stecyk. I had no problem putting away my career and putting my attention on Caballero, Lance, McGill and those guys. I never had an issue with those guys becoming great and me behind them. In fact, I think I might have gotten more gratification out of it than from my career. It was just more gratifying. When you’re doing it for yourself, you have to deal with all of the insecurities of, “Am I good enough?” With those guys, I just got to focus and help them achieve what they wanted to achieve and it suited me better.

You got gratification from helping others.

Yep. It was super fun, and I liked being in a position where I could be more involved in what products we were going to make and the strategy. It gave me a chance to really expand. I liked the mental involvement of constantly solving problems and looking down the road at what we had to do to stay on top. I really enjoyed that.

Did you guys have some foresight that, if you hung in, it would come back?

Well, that’s the thing that kept us going, but I don’t know if I really believed it. There was a time where the only reason we stayed in business was because we were selling roller-skate wheels as well. I can’t tell you how many conversations I had with Fausto going, “Man, is this ever going to come back?” It was really slim pickin’s. There was a time where we didn’t even have a skateboarding magazine supporting skateboarding. We were a sport without a magazine to document it, but I remember the day it changed. We kept doubling down, and the one thing I credit George with is that he never gave up. He was on it, pedal to the metal, going full throttle. He approved the budget for the very first Bones Brigade Video Show, which was a ballsy move because it cost us a lot of money at the time. That video is what turned everything around for us. I remember, at that time, we had gone to this ramp contest in Tahoe where Lance lit his board on fire and won. I went back to Santa Barbara after that contest and George pulled me into his office and he said, “Sit down, I have to share something with you. Our videos are making such a big splash in skateboarding. They seem to be lifting the whole tide in skateboarding and the sport is coming back.” Then he handed me an envelope and said, “Go ahead and open that.” I opened it and inside was a check for $15,000.

No way!

This was in late 1984. I hadn’t seen money like that in years. He said, “The sport is really coming back. We’re going to really ramp things up and you’re going to need to make an hour-long skateboard video every year from now on, so you need to get busy on that right now.” That was it right there. That was a turning point where it was like, “Wow. Skateboarding is really coming back.” And that’s exactly what happened.

So the video lifted it up so other people could see what was possible on a skateboard?

What we found out, Steve, is that our distributors that carried our product all over the world were saying, “Look, what you don’t realize is that the magazines, as great as they are, they don’t show you how to do these tricks. They only show you a freeze frame at the top of the trick. They don’t show you how to get there or how to get out of there, but these videos do.” The videos were allowing these kids to sit in their living room and figure out how to do a handplant or an ollie or a finger flip or whatever it may be. They said, “For every kid that buys one of these videos, 50 kids see them. You’ve got to come out with another one.” There was this crazy demand for these videos. Where we thought we’d only sell a handful of them that would play in skateboard shops, we didn’t realize, when we were making these things, that 70% of the country would have VCRs. It was just one of those things that coincided, like when the pool revolution coincided with the drought to make it possible for more pools to be empty and the urethane wheel to be invented at the same time. The cheap video cameras and the VCR revolution and skateboarding all came together and created an explosion.

It all happened at once.

Yeah. Fortunately, we got to own that market for about three years, until Vision started doing videos and then Santa Cruz started doing videos. After ‘89, every skateboard company, surf company, BMX company and snowboard company suddenly had their own in-house productions and were making their own videos. It was something you had to do.

How did you come up with the idea?

Well, D. David had gone to film school and he came up to me one day and said, “My partner, Dan, and I think we can make you a skateboard video for $5,000.” So I went and proposed it to George and he said, “Shoot, well, for $5,000, why don’t we try it?” So we had it all set up to go. The day that we were first set up to shoot it, D. David got his first commercial part as an actor, so he couldn’t be there to direct it. It fell in my lap to direct it, and I didn’t get along well with his friend, Dan, at the time, so after the first day of shooting, I just decided that I would do it myself, even though I didn’t know what I was doing.

How did you approach the filming?

I just got a video camera and started shooting ramp skating and pool skating. I’d arrange these sessions, like a Gonzales pool session or a ramp jam at Lance’s house. I would go down and shoot Tony Hawk and Steve Steadham at Del Mar. We found a ditch and I would bring Tony, Mike and Steve to ride this ditch and I’d shoot them. I’d see these guys playing with fingerboards in empty sinks, and think, “That’s a cool thing. Let’s shoot that.” Whatever dumb things I saw, I shot, and I amassed all this footage. Then I started cutting the footage into edits. Then Stecyk and George and I would look at the various edits and say, “Why don’t we open up the video with this piece and transition to that piece?” It was kind of like that. I made the first three Bones Brigade videos in my Hollywood apartment editing on my kitchen table.

What were you editing on at the time?

It was a tape-to-tape system called the Sony 5850. It was two three-quarter-inch tape machines with a little controller. That’s what I used for the first three or four years before we started doing Super 8 and 16mm and branching out and getting to use more lenses and stuff like that.

Then you went from your apartment to a place over off Glendale Blvd, right?

I went to a studio in Silverlake on Glendale Blvd, but it was still three-quarter inch, tape-to-tape. You came over there a bunch of times with your projects and I made copies of your rock videos for you and things you were doing at the time.

Yeah. Before the Bones Brigade, what was it like within the whole Zephyr scene?

Let me throw this at you. I’ll tell you three times that Tony Alva stopped my heart and made my heart skip a beat. One of them was at Bellagio. We were all skating there one day, and the sessions we had in those days were so incredibly magical. There would be 50 or 100 kids and most of them weren’t skating. Most of them were just sitting at the top of the banked wall and watching. That’s just the way it was back then. It was a scene. On this one day, I saw Alva drop down the giant Bellagio wall and come up to the very top of the wall in the middle section and get into this beautiful arch and right before he was about to make the drop back down the bank after he passed the building that was below the bank, he did this quick little top turn with his ankles and then he dropped into this flat out crouch. It was the same kind of stylistic maneuver we had seen done by the famous surfers of the day at Sunset Beach in Hawaii. Tony then took the transition from the bank to the flat bottom in that completely tucked position which was mind-blowing because he did it perfectly with perfect style and absolute force. He didn’t miss a beat. I remember seeing him do that and it just flat out blew my mind. Of course, I followed him a second later and did the same thing. I had to. He gave me no choice. The next thing he did that blew me away was at the second pool that we all skated called the Rabbit Hole in Santa Monica. The very first pool we skated was called the Barrington Pool. We called it the Birdbath and it was on a giant Bel-Air or Brentwood estate. It was an old-fashioned pool from the ‘20s. It didn’t have coping and it wasn’t even vertical. It looked like a giant birdbath. That was the first pool we rode. The second pool we rode was the Rabbit Hole on Marguerita Street in Santa Monica and it was a house remodel. It was a tiny tight little pool that was super claustrophobic. Jim Muir used to call the Rabbit Hole a health hazard because it was so tight. It was so small that you couldn’t make it over the light because it was so vertical, but I saw Tony do a completely vertical Bertlemann turn in that pool. To this day, I’ve never seen any skater do anything like that again. I don’t know how he did it, but he did it and it was shocking. He was completely vertical doing this Bertlemann turn, completely laid out and his wheels skidded on the tiles and, as his board came down, somehow he managed to tuck it back under his body. I don’t know how he did it. The third time he blew my mind was when he and Biniak and I were skateboarding this pool in the San Fernando Valley called the Devonshire pool. It was the best pool I’ve ever ridden in my life. It was a giant peanut kidney combination and you could carve both ways. It had a huge shallow end and it had perfect transition and perfect coping. We used to go to this pool a lot. It was at a house that had a double piece of property and the pool was on the second piece of property and there was nothing surrounding it. An old woman lived in the house and she could never hear us. Anyway, Biniak and I were in the shallow end waiting our turn and Tony was skateboarding and, suddenly, he did a backside edger on one of the walls and his outside wheel went up out and over the back of the coping and then back into the pool. I’ve seen skaters do this by mistake and come close to destroying themselves, but somehow Tony pulled it off. It was so radical that Biniak looked at me as if he had seen a ghost. I’ll never forget Biniak’s expression as long as I live. Tony continued his run and then Biniak turned to me and said, “Don’t say anything to him about the fact that we saw that or else he will never stop talking about it on the drive home.”

[Laughs] Biniak didn’t want to hear him talk about it all the way home?

Oh no. Biniak said, “Don’t mention it because you’ll never get him to stop talking about it.” Those sessions were so raw and it was so fresh and we were still riding Zephyr boards and wooden boards. Then we were riding the Keyhole in Beverly Hills and then the Canyon pool. It was before pool riding became popular. It was so early in the whole mix. I remember learning a frontside kickturn. Check this out, Steve. Back then people didn’t think frontside kickturns were possible. They didn’t think you could get your body in that position, with your back exposed to the pool. I remember arguing with Biniak one day about the possibility of doing a frontside kickturn, because he didn’t think it was possible and I said, “Yes, it is possible. You can do it.” Then he said, “Well, then why don’t you do it?” I said, “I can’t, but you can.” This is the absolute truth. I looked at Bob and told him he could. So then I got out of the Keyhole and I went to the top of the deep end and I was like, “Okay, Bob, try it.” He dropped in and did a frontside kickturn about three feet up the deep end and he made it. Then I said, “You got it. Do it again but a bit higher.” He then tried again and went halfway up and he made it and, by the end of that session, Biniak was doing frontside kickturns on tiles. From that point forward, we all did them. That’s how it worked back then.

It was all possible.

Exactly. Cut back to the Devonshire pool a few weeks later and there was a session with all of us – Jay, Tony, Muir, myself and Paul Constantineau – and Stecyk was shooting photos and it was an absolutely wild session. I go to drop in and, by now, I’m doing forever kickturns frontside, you know back to back tile to tile frontside kickturns. No one, at that point, was doing that yet. They could do one offs, but that’s it. So I’m doing forever kickturns frontside back and forth. I finish my ride and return to the shallow end and Muir looks at me and says, “You’re an asshole.”

[Laughs] Yes!

One thing that most people don’t know is that Jay Adams was not a great pool rider at first. He and Paul Constantineau were three years younger than the rest of us, and I don’t know if it was just that they didn’t have the strength yet, or what, but those two guys didn’t take to pools immediately with what they would eventually do. Jay became an amazing pool rider but, in those days at that Devonshire session, there’s a shot of Jay that Stecyk took and he’s doing an aerial barefoot off the hip. Jay wasn’t making a lot of stuff that day at all, but he was going all over the place like a monkey doing all sorts of crazy things. He wasn’t making anything and he wasn’t really going that high, but he was going everywhere. He was doing every run differently. It was like watching an electron bouncing off walls.

He had quite a bit of energy.

Oh yeah. One of the funnest things about all of those early pool sessions was the drive to the pool from Santa Monica. I was the only one with a car. Jay would usually sit in the front seat of my car with Tony and Biniak and Muir in the back and Jay would spend the entire drive hanging out the window. I don’t say this with any exaggeration. He would literally scream insults at every human being that came within shouting distance of my car. He insulted everyone. It was so funny that he would have us howling everywhere we went. I was always worried that someone was going to notice my car and some day they would see me driving alone and pull me over and kill me for something that Jay had screamed at them.

You worked at the Spaghetti Factory too?

I worked at the Old Venice Noodle Company that was on Main Street in Santa Monica between Ocean Park and Rose. That’s when Main Street Santa Monica was pretty much a boarded up ghetto. The Old Venice Noodle Company was the third business to open up in that area and that began its renaissance. It was also the first restaurant in Santa Monica that allowed teenage boys to work there without having to cut their hair or put their hair in a hairnet. That was a big deal back then. That was a crazy fun place to work. There were 15 bus boys and 15 waiters and waitresses every night, so there was constant mayhem. I remember one night we wrapped a waitress in cellophane and carried her out to one of her tables and left her there stuck in front of her customers.

Yes! You were working as a waiter?

I was working as a bus boy. I was only 16 years old, so I couldn’t be a waiter. I was cleaning tables and stuff. I always had jobs when I was a kid. If I wasn’t delivering newspapers or slicing vegetables in a restaurant, I got a job as a bus boy. When I quit that job at the old Venice Noodle Company, that was the last “job” I ever had in my life. From then on, it was all about skateboarding. How about you? What was your first job?

When I was 13, I had a job as a dishwasher at a restaurant by my house. I saw a skateboard at a bike shop and there was no way I could con anybody into buying me the skateboard because it was expensive, so I got a job as a dishwasher so that I could buy the skateboard. I bought it and it was a piece of shit. I was like, “I can’t believe I just worked that long and this board I bought is just a hunk of shit.” We were making our own boards then and this board was just lame and I was working for this guy that just yelled at us constantly at the restaurant.

[Laughs] Yes! When you were with Santa Cruz, what was the most money you ever made per month? Do you remember?

The most I made was $1,000 a month.

That’s it? $1,000 a month?

Yeah. I was getting a salary, but they couldn’t make my boards when it was happening. When they finally got it together, it was over. I skated for Independent and I didn’t make that much money, but I was like, “Wow, I’m actually getting paid to skateboard? That’s insane.”

What people don’t realize is that we had the black cloud of 1964 and 1965 hanging over us when we were pro. Everyone thought skateboarding was going to end any second. It was like, “How long is this going to last?” It had already come and gone once in the mid ‘60s. I think a lot of people thought it would come and go again. There was that big fear always in the background. When it happened, people were like, “Oh, you were right. It really did crash again.” It really did disappear again. That was terrible.

It crashes constantly still. It hits plateaus and then levels off and has its decline and then it grows again.

Yeah. I have a question. Were you an artistic kid or did you become an artist later on?

I would say later on. I liked painting and all of that, but my brother was the artist.

How did you get into art? What happened? What made you wake up and start taking canvases and throwing images and paint on them?

There was a time when Ned Evans was doing a fundraiser for Surfrider like 15 years ago. Ned said, “Here is this miniature balsa wood surfboard thing. Do whatever you want with it.” So I wrapped some leopard skin around a canvas and then I elevated the board and I had an old car emblem from a Ford Futura and I mounted that on top of the board. A couple of renowned artists, like Laddie Dill, were like, “Wow. That was our favorite piece in the exhibition.”

No kidding.

It was cool. This guy Norton Wisdom owns it now. I was like, “Interesting.” So I did some more and then I just started going.

So you started liking doing it?

Yeah. I like doing it. You can say things through your art. I played music too. We also made flyers, films and videos. It was all within that world. At Santa Cruz, when I was doing SOS, I was doing the ad campaign and I had written up my concepts and I brought in my proposal on a yellow piece of paper. It wasn’t typed or written with any type of structure. It was just ideas of what I wanted to do and Novak was like, “There is no way.” I was like, “What do you mean?” He’s like, “There’s no way we can pull this off. It’s too much too soon.” I was thinking, “Why not? You have the money.” He was always complaining that he didn’t have any money, but he did. I wanted to do clothing. I was borrowing a little bit from Malcolm McLaren and his whole scene. I also wanted to make a film. This guy I knew was a friend of a friend of the director of Rebel Without A Cause, Nicholas Ray. He wanted to do a skateboard film and I told him he should watch Skaterdater. I wanted to do this film called Going Down and I wanted to shoot it in black and white on Super 8. The story was set in San Francisco. There are two kids skating this hill and getting chased by the cops and the cops go after one of the kids and that kid happened to be black. That was the concept, but Novak didn’t dig it. I wanted to make posters of it and slap them all over, but he said no.

Let me ask you something. You got into filmmaking and you’re an actor and an artist and a musician. Is it skateboarding that opened the door to make you realize you could do this stuff or would you have done this stuff anyway?

I think skateboarding was the gateway for sure, without a doubt. It introduced me to all of these things. I remember doing a handstand on my cul de sac on a Wayne Brown skateboard, and I couldn’t do a handstand, but the picture made it look like I could do a handstand. Then I learned how to do a handstand.

[Laughs] Yes!

I was like, “That’s cool. That’s some trickery. That’s interesting.” Then I had a brother who was an artist and he made surfboards and he made cartoons and I would flip the pages for him because he would have to draw 5,400+ pictures to get a frame for an animation cartoon. It was influenced by the guy that did Five Summer Stories with the guy sitting on the toilet. I had my older brother, who was my best friend, and that was monumental for me. He could do anything. I was like, “That’s cool. I’m just the athlete.”

I was curious about the skateboarding question, if that is what opened the door for you as well, because it was for me. It’s not just about skateboarding, but skateboarding as a professional, and being able to be someone in the sport, I experienced that and went, “I can’t go backwards now. I can’t just leave this and go sell cars or life insurance. I’ve got to make something of my life. I can’t let skateboarding in backyard pools be the highlight of my life.” It made me realize that I could do more with my life even though I had an inferiority complex because I hadn’t done well in school. I hadn’t done too well in school, so as a result of that I always thought I was a dummy.

I didn’t do good in school either. I was just excited to pass a class so I could keep going.

Did it give you a complex like you weren’t smart?

A little bit, but then skateboarding gave me a boost of confidence that I was way smarter than I thought.

See I didn’t interpret smart when I skateboarded. We were always told that we were wrong for skateboarding because we were kicked out of everywhere we tried to skate, so I got my self-esteem kind of beaten out of me because of that. It was like, “Why would you choose to skateboard, you dummy?” No one wanted us around and everyone hated us and no one respected it. If I had played tennis, I might have gotten some self-esteem out of it, but you couldn’t with skateboarding, other than what you got from your friends, which, of course, was super valuable. I never got it from the “establishment.”

The establishment looked down on it.

Totally. It was that and a combination of doing poorly in school and having everyone look down on skateboarding that I was like, “Man, I don’t have much of a future for myself.” I figured, when I was in high school, that I was going to be a plumber. That’s what I was aiming for. The reason I say that was because I figured I could do it. That’s no reflection on the trade of plumbing. I just thought that was probably what I was going to do.

Wow. I didn’t even think about what I was going to be doing after high school. It was happening in high school for me in my skateboarding career. I was 16 when it started to fly.

Yeah. See I was already out of high school when it was happening for me. I was on the Zephyr surf team in high school and it wasn’t until after graduation that it really started happening for me. The Bahne contest happened when I was in 12th grade. Here’s a piece of information that people don’t know about the Zephyr team, since you asked about that. Tony Alva, Jay Adams, myself, Allen Sarlo and Nathan Pratt were on the Zephyr surf team. We were the junior Zephyr surf team. The older guys were Ronnie Jay, Bill Urbany, Wayne Inouye and Wayne Saunders. The Zephyr surf team was the absolute dream team to be on if you lived in Venice or Santa Monica. The only reason the Zephyr skateboard team happened was we had a surf team meeting one night at the Zephyr shop and we were all sitting around there. Matt Warshaw was on the team too. Tony Alva suddenly said, “We have all these great skateboarders on the surf team. We have myself, Jay, Stacy… Why don’t we start a Zephyr skateboard team?” It was one of those random things where Jeff and Skip looked at each other and said, “Well, yeah, why not?” After that meeting, they brought on Muir, Biniak, Shogo, PC and Wentzle.

I want to talk about when the urethane wheel came on the scene.

I remember the first time I saw the urethane wheel. I heard it was coming out, but I didn’t believe it. We had a skate scene in my neighborhood and there was a kid down the street named Kevin Farley, who would eventually become one of the very first computer programmers. He was a super bright kid. He told me, “I’m going to buy a set of these wheels.” I said, “How much are they?” He said, “They are 50 cents each.” I said, “Are you out of your mind? You’re going to pay $2.00 for a full set of wheels? That’s ridiculous!” There was no way I was going to pay that much for skateboard wheels, so he went out and got them and put them on his board and came to my house one day and said, “You’ve got to try these.” I got on his board and I pushed down my driveway and did a really hard turn out of the driveway and onto the sidewalk and the wheels didn’t skid out. Then I went up to the corner and hit a hard turn and they still didn’t skid out. I swear to you, from that day forward, he came to my house every day after school and he would sit on the lawn, and I would ride his skateboard with those wheels until I got my own. I remember his board was homemade and he had painted an American flag on the bottom of the board. Fifty cents a wheel was like extortion back then.

That’s nuts. Boards were not cheap either.

Yeah. You couldn’t buy a board back then. We were still riding homemade boards. In fact, I still have the board that I transitioned from clay to urethane wheels on.

Oh, you saved it?

I saved all my boards, Steve. I have my very first board that I rode as a kid. It’s so old that it’s composting and rotting. I’ve saved all of them. I’m trying to put my entire collection together to give away to a museum or something. I hate the fact that these great boards just sit in my garage in total darkness. I want to have people see this stuff.

Right. When you started skating in contests, how was that for you as a kid competing on this toy? I mean we didn’t look at it as a toy, but other people did.

Yeah. We never looked at it as a toy. Actually, I loved contests. When we were skating prior to contests, what we were really doing in our imagination was surfing. It wasn’t skateboarding, it was surfing. Whether I was on a sidewalk or riding the banked playgrounds, it was always surfing. Everything was a surfing maneuver. In my head, I was either Gerry Lopez, Larry Bertlemann, Barry Kanaiaupuni or Terry Fitzgerald. It was like, “Who am I going to be today?” If I was going into a tube, I was Lopez. If I was going to do a cutback, I was Bertlemann. If I was going to do some crazy bottom turn, I was Kanaiaupuni. If I was going to do something with beautiful style, I was going to be Terry Fitzgerald. Here is another piece of trivia for you. I remember the very first time I saw Tony Alva skateboard. I didn’t even know who he was. I was probably 13 years old and I was at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium standing in line to go in and watch a surf film. There were probably 300 surfers there in line to get tickets and there was a little roped off area. Tony was just a little kid riding this Hobie board and he was jumping the rope and landing on his board and then going back and forth. He had such a beautiful style and it was so clean. I remember standing there in line watching him and going, “Wow! There’s somebody else that skateboards in this world!” We didn’t know that other people skated besides the kids in our neighborhood because we hadn’t seen them. From day one, we had a skate scene in our neighborhood and I don’t know why we did but we did. Whenever we’d go to Paul Revere, we’d see evidence that other skateboarders had been there, but we never saw them there. We had Mar Vista School that was right by my house. We’d go to Brentwood and Kenter and skate there. At that time, we didn’t even know that Bellagio existed. When we got our parents to do a good favor for us, they’d take us to Paul Revere and drop us off and we’d skate all day there on Saturday.

You never got chased away?

No. Nobody tried to chase us away because no one was there. We were always trying to hustle a ride to get to these places. When we went to Mar Vista, we could skate there, but so often we got kicked out by this janitor. He kicked us out so many times that we actually had to start skating Mar Vista School at nighttime because it was the only time the janitor wasn’t there. It was tricky skating it at night because you’d hit rocks or cracks on clay wheels and it was pretty hairy. We’d go there at nighttime and we had our little PF Flyers, the deck shoes. We didn’t even have Vans then. We had Pendleton shirts and Levi’s. We were 13 years old and, as far as we were concerned, we were the only skateboarders on planet earth.

You had no idea that there were other guys skateboarding anywhere.

No clue. We were serious about it too. We would have our own little competitions and we took it really seriously. It was a big deal. We had a whole scene in my neighborhood and every kid had a board. When the urethane wheel developed and then the Bahne flexible board developed, that’s when you suddenly started seeing people ride skateboards. We were like, “Wait a minute. There’s more people doing it now.” By that time, I had become a good enough surfer to get on the Zephyr team, which then introduced me to Jay and Tony and all the other guys. That’s when we all started mixing together.

You guys started the team and you started competing, so the competition team started before the contest at Del Mar.

Yeah. We were already the Zephyr competition team before that. We started on the Zephyr surf team and we were doing that for about a year and then we became the Zephyr skateboard team, in addition to the surf team. Then that competition came up and Jeff and Skip decided we were going to go down to that. It was the first time most of us had ever seen a skateboard contest.

That’s what I’m saying. That was your first contest.

Yes. It was our first contest. I remember getting out of the car at the Del Mar Fairgrounds and I had never seen more skateboarders in my life. It was like, “Wait! What? How is this possible?” It was like going to another planet and suddenly you’re seeing all these other humans that you had never seen before. It was such an eye-opening experience. From then on, there was a contest every other month somewhere like Ventura, South Bay and Huntington Beach. There was something going on everywhere.

Did you dig competing when you were on the Zephyr team?

Yeah. I started to get my bearings and I liked it. I liked the whole mix of it. I liked meeting everybody and getting challenged. I liked seeing all the tricks people were bringing to these events. I just liked the whole experience.

You had surfed in surf competitions prior to that though, right?

Yeah, not too many, but I liked that as well. The Zephyr surf team challenged the E.T. Surf Team in the South Bay to a surf contest and they agreed to do it, but only if we came down and rode their beach. The judges were Stecyk, one person from our team, and one person from their team, and Kurt Ledterman of Surfer Magazine. They had Mike Purpus on their team and we beat them.

Oh, you did?

Yeah! I remember being in the water that morning and it was kind of a big day and I dropped into this big close-out and I had a really good backside re-entry on this gnarly wave and Mike Purpus looked at me and goes, “That’s the best thing I’ve seen all day.” That was a compliment that I carried with me for months. After my heat, I remember seeing Tony compete. Tony was never a “ripper” surfer, but he was a great surfer with perfect style. I remember seeing him drop in on a wave that morning and his finesse and his timing and his style were just impeccable. He was never a ripper like he was going to thrash and get grinds and stuff like that, but he surfed beautifully. Jay was a ripper. Jay was a real surfing terror and Allen Sarlo was a terror in the water as well. Muir, Biniak, Shogo, Paul Constantineau and Wentzle were not on the surf team. Those guys came on later, on the skateboarding team. When the skateboarding team was formed, those guys were brought on. We eventually brought on Baby Paul and some other kids as well. Those guys didn’t make the surf team.

Did you guys keep surfing or did the skateboarding thing just take off for you?

Well, we always kept surfing but, in the height of skateboarding, I was doing it so much that surfing took a backseat. I was enjoying skateboarding so much that I didn’t need to surf for a while. Then there would come a time where I’d be away from the ocean for such a long time that I would start dreaming about it and thinking I have to get back in the water and I eventually would. I would realize how important it is to me. That’s happened throughout my whole life. I will go away from it for a year or two and then I just can’t take it any longer and I have to get back to the water. With kiteboarding, today, I never thought I’d be having this much fun in the water at my age. The other day I got out of the water after a long session of kiteboarding and the only reason I got out is because I was so tired that I thought, “If I don’t get out, I’m going to hurt myself.” I must have done 50 aerials and 100 Bertlemanns turns. It is so much fun. You of all people would go ballistic on a kiteboard. It would be your most favorite thing guaranteed, because I know the way you skate. You’re one of the few skaters that never does anything twice. Every run you take, it’s like the first time you’ve taken it and that’s what is so great about kiteboarding. You’re getting hit with so many obstacles and you never know where they’re coming at you and you’re bouncing off everything and the ride out is as fun as the ride in. Your style is tailor made for it. Consider it something you have to do.

Interesting. Yeah, but you have to get the rig and everything.

Don’t worry about that. Just learn it first. I’ll take you up to the California delta, and get my teacher to teach you. You’ll really dig it. It’s so much fun. To me, it’s all the same, whether it’s surfing or skateboarding or kiting. It’s that same experience of looking for stillness in the middle of all this chaos. You’re trying to push something as hard as you can and, at the same time, you want to be still inside while it’s all going on.

And you achieve that?

Yeah. I try. When did you learn frontside aerials?

I saw Orton doing them at Skatopia when he rode for California Pro Am before Sims. He would just carve down and then do some weird giant crazy air into the Skatopia halfpipe. Then I saw the picture of T.A. Then the Hester stuff started and I didn’t know how to do an air. I skated Spring Valley and then I skated Upland and I got good enough in those two contests to where I was in front in the point standings.

You weren’t doing aerials by then?

Krisik who was my team manager was like, “You need to put an air in and then no one can touch you.” I was like “Okay.” So I went to the Winchester washboard and I learned frontside airs there.

The washboard was where I learned to do backside airs. It was the perfect place.

Yeah. I also learned rock n’ rolls in that little egg bowl thing in between the washboard and the pool. I learned airs, and then we went to Newark, and it was happening. It was like, “Okay, I’ve got my frontside air and my arsenal of tricks.” I remember there was a point in that contest, going from the top eight into the top four, and Valdez is showing the invert and Blackhart had rolled in over the flat coping, and I remember there was a tie going into the top four.

Who was the tie between?

It was between me and Bobby Valdez. Bobby had done the handplant and there was a tie. With the rules that they had, they would take your two previous run points and add them together and whoever had the higher score would advance, but they went against that and took just one score instead. They had the rules written out, but they didn’t go with those rules and so he advanced and I was pissed. I was like, “This is not cool. If they had followed the rules, I would have advanced into the semi-finals.” I was pissed. I was like, “That’s rude. It’s right here in the rules written out, but whatever.”

Wow. Even though you didn’t get in the finals on that one, you still won the overall series.

Yeah. I didn’t even win a contest. I got 3rd at Spring Valley, which was the first one. That was the first big pool contest, which was dicey, and they had no idea what was going on. Then we went to Upland.

What did you get at Upland?

Mike Weed never showed up and I got fourth at Upland. Dunlap got 4th at Spring Valley and 3rd at Upland. Then Dunlap and I were in a tie for first overall. We weren’t even thinking about that, until then, and then we realized it was about the overall scores.

What did Steve Alba get at the first Upland?

I think he got 12th. He blew it.

Okay. Just a quick note. I actually thought that Scott Dunlap was going to be a great skateboarder. I thought he was going to be someone to really contend with but, after Upland, that guy just disappeared. He was doing all sorts of crazy things and learning so many tricks and, all of a sudden, he was gone. That was weird. I did frontside airs pretty early. I think I learned them around the same time that Tony did. I learned them at Paramount. I tried to do another form of aerial at Upland way earlier and I actually pulled it off a couple of times, but it was more like a backside air crossed with a bunny hop air. I tried to do it for Bolster one day in the big pool at Upland because I had made it a couple of times. When I say aerial, I mean that I was just bouncing off the top. I wasn’t really getting any higher, but I could do it. I tried to do it for Bolster and I couldn’t, so I lost that moment. It was one of those things. I did learn the frontside air at Winchester at that contest and then I remember learning the backside air and it came so naturally on that washboard. It was so much easier to do it there.

That washboard was a great place to learn things.

It was super good because you’d get the rhythm of those bumps and then you’d hit the halfpipe.

I learned a couple of things there. Then Newark was like a turning point for me because Terry Nails showed up in his clothing regalia and punk rock was starting to be introduced into skateboarding.

Was it Terry Nails that started it for you? You hadn’t gone to see punk rock bands before that?

Well, we had gone to a couple of clubs because my brother was 21 and I was 17, so I could use his ID to get in, but Terry Nails was a huge influence on me.

I had no idea. How was he dressed?

He was dressed in all black with a cowboy hat on and a cow skin vest. He had on some kind of sunglasses and I was like, “Look at that. That looks really dope.”

[Laughs] Yes! Steve, do you know what’s amazing about that? That look was completely anti-surfing at that time. Surfing was sunny and colors. All of a sudden, there was this really dark gloomy dramatic look. It was so different that I can see where that would be really attractive.

It was an introduction to fashion and consciously saying, “That looks like an interesting way to present yourself through what you choose to wear.”

A lot of it was loud with the leopard skin and those dog bracelets and stuff.

Yeah. You had all sorts of things like that. It seemed like a lot of it was coming from art school students and stuff.

Remember those contests at Upland and all those punks that would show up with the mohawks and what a big part of the scene that was back then? At those contests, it was all punk rock music back in those days. Everything was punk rock.

It came in and took over by storm. It was a crazy onslaught of, “Here is this new movement and it’s definitely involved in skateboarding.” It became part of skateboarding and skateboarding adapted to it.

To me there’s a transition song off the first Van Halen record, “Runnin’ With The Devil” and that song was the theme song during the Hester/Upland contest. I was like, “Wow. What is this band?” Van Halen was pretty new at the time. After that, it was all punk. It was as if Van Halen was the last gasp of rock n’ roll and then everything turned punk after that.

Really? That early you think?

It seemed that way. I’m not saying it happened exactly at that time, but it seemed like that was the demarcation point. We had been listening to the same rock n’ roll music for a long time and then Van Halen came in and our attention was on that and, boom, it changed rock n roll, and then skateboarding was embracing punk.

Embracing it hugely.

Yes. I just thought of something I have to share with you. There can’t be any joking. This is serious.

Okay. Share. Go on.

Larry Gordon passed away recently and that guy gave me the most amazing opportunity of my life and, over the years I had a few chances to thank him and, during the last few months of his life, I knew he was getting close to death because of information I was getting from Dave MacIntyre. I was in the process of writing something to Larry, but I didn’t get it to him in time. The reason I bring that up is because it made me think of other things I wanted to say. It made me think of how lucky we, as a group on the Zephyr team, were to have Stecyk, and that he was a part of that scene. It’s not that Craig could just shoot pictures. He was a really good photographer and he was a really good writer and he was really subversive and well-educated and he was paying top quality attention to what we were doing and then processing it inside himself and putting it into his articles. Stecyk was a really rare person in the surf world at that time. He was as odd as a human being could possibly be with all of his various talents and eccentricities. When we used to go on photo shoots back in the day, Craig always insisted we shoot in the morning or the evening. He never explained why. At the time, I just figured we were doing it because he liked being in the cool air. Of course, it was because he wanted the good light, the morning light and the evening golden hour and so many of his iconic photos have the beautiful exploding back light. He was the kind of guy that never explained himself. You either got what was going with him or you didn’t, but he wasn’t going to take the time to explain it. When I look back on the photography that he did of all of us, we were so lucky. It wouldn’t have existed without him documenting it. He had a tremendous effect on all of our careers and on the skateboard world itself.

He created the myth behind it with the subject matter that was real.

Oh, without a doubt. He created the whole fiction, the whole narrative and the whole mythology. He gave it a name. He was noticing something. He’s an incredibly astute guy. The other thing is we all came from an area where we all had chips on our shoulders. We all lived either in Santa Monica or the Venice area and our local beach break was Bay Street. To the north of us was Malibu, which can be a world class surf break, so we were looked down upon as having nothing but garbage to surf. To the south of us was Orange County where the magazine was, so we were looked at if we were living in a no man’s land. Stecyk had a major axe to grind to prove to the world that there was talent where we we lived. It was important to him to prove to the world that they didn’t realize what kind of skating was happening in this hell hole. There’s a lot of talent here and he knew it. Even though we didn’t have much going for us, there was a helluva lot of talent and he drove that home through his photographs and articles. Contrary to what Craig would lead one to believe, he was dead serious about what he was doing at the time. He took his photography and the conception of his ideas very seriously. “We” as the Dogtown crew are so overwhelmingly fortunate that he was there and that he documented all that happened in that very short amount of time.

Yeah. He’s such a good writer as well.

He’s an amazing writer, but what he really is, is an amazing observer and he also saw skateboarding in a bigger context. I think Craig is the first person I ever heard use the word “culture.” I didn’t even know what that word meant when I was in high school. I heard Craig say it all the time, the surf culture and the skate culture, and I didn’t know what he was talking about. He was just a really strange hybrid of human; surfer, skater, artist, photographer, post hippie and street person, but also a marketing whiz and market strategist with a very strong political mind. He was so ahead of his time in how he fused art and surfing and skating and the street. There weren’t a whole lot of surfer artists or skateboarder artists at that time. He was a real outlier and trailblazer.

I think Craig has always been ahead of his time.

Yes. On another note, I’m curious to get your take on something that’s been on my mind. I have always thought of our generation as the purest generation of skateboarders because we started when there was nothing and skateboarding didn’t even exist yet. We had the blankest canvas of any generation perhaps. You couldn’t even call yourself a skateboarder back when we were skateboarding as kids because it didn’t exist. Now I’ve come to realize that maybe we weren’t the purest generation because when I look at Rodney Mullen and Tony Hawk and how long those guys have skateboarded and the fact that they know nothing else other than skateboarding. They’re not surfers. They were never surfers. They are pure skateboarders. That’s all they do and that’s all they know and they don’t leave their skateboards anywhere. They travel with them everywhere. I think maybe they are the purest skateboarders. Maybe nobody is the purest. I don’t know. I’ve wondered that at times. We had surfing. To us, it was surfing and a broader expression and form of movement. To them, it was a whole different deal of just skating that was influenced by nothing else.

I think even more so for Rodney.

Yeah. Rodney is like Jimi Hendrix in that Hendrix was never without his guitar. If you go to dinner with Rodney, he carries his skateboard with him to the table. It’s literally with him all the time. When we were looking at the rough cuts of the Bones Brigade film, we would meet at Josh Altman’s house in Venice. When Rodney would drive over there from Redondo Beach, he would get out of his car and grab his skateboard and have it next to him the whole time in the editing room, watch the film, take his skateboard and go back to his car and leave. His skateboard never left his side. I’ve never seen that kind of attachment and connection. He’s in his 40’s and skating multiple hours every day is still a huge part of his life. When we told him we were going to go to Sundance with the Bones Brigade film, as excited as he was, the first question out of his mouth was, “There’s snow up there, right?” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “Well, is there a place I can skate?” I said, “There are probably some underground parking garages under the hotels we can find.” He said, “Well, can you make sure we can find those?” He needed to know that there was a place up there to skate. Every night at 11pm, he would pack food in a blue box and he would disappear for three or four hours by himself. After a few days, we were wondering where he was going, so we went looking for him one night and we found him skateboarding. It was heavy. He wasn’t just skateboarding. It was like looking at a monk going to his cave. This was a ritual with an intention behind it. He was focused and he had his game face on, and he didn’t like us being there. There were a few laughs, but then it was like, “Okay, you’ve had your laughs, now get out of here and leave me alone so I can do my thing.” Here’s another thing I wanted to talk to you about. I have always wondered if we had the right skateboards at the time we were coming up. At that time, we couldn’t buy them. You had to make them out of roller-skates and boards. If you did it, you did it for the pure joy of it because there was zero to get out of it. There were no contests. There were no parks or shops or anything.

What you would get out of it is your creation though. You’re creating a piece that you would attach to the wheels and trucks and there was this connection of, “I made this!” It’s like making a spear.

It was very personal and you’d keep that board and ride that same board for a year or two.

I used to make wide boards intentionally, so I could knee paddle it and then jump up like I was riding a longboard.

Wow. How wide were they, like 8 inches?

No, wider. One of the pieces of wood that I used had a natural concave to it because it had warped. I surfed for Wayne Brown Surfboards and I got some laminates and I put round little bits of sandpaper on it for griptape. I would kneeboard on that skateboard, so I could spring up to my feet like I was catching a wave.

That’s amazing. There again, in your mind, you were surfing. Here’s something that’s weird and I’m curious if you experienced this. When we were on the Zephyr surf team, it was only the junior surfers that skateboarded. Allen Sarlo, myself, Tony, Jay and Nathan skateboarded, but the guys that were older than us, like Ronnie Jay, Wayne Inouye, Bill Urbany and Wayne Saunders, didn’t ride skateboards. I don’t know why it was that our generation picked it up and theirs didn’t. We were serious about it from day one and they didn’t even think about it. It almost would have been weird if they did, at the time, because it was considered a young person’s thing to do, if you did it at all. It’s such a strange thing. Maybe they didn’t do it because they were older in the ‘64-’65 downturn and they were over it by that time. I don’t know.

Maybe they saw a skateboard as just a toy.

Yeah. When we were at Sundance, I got a chance to hang out with Rodney, Lance and Tommy. We all stayed in the same house for a while, and we hadn’t been together in a really long time, and those guys started asking questions about the old days and what it was like. They wanted to know about Jay and was he really that good and what was he like. I was explaining to them that Jay wasn’t great, but there is no way to describe how good he was. He wasn’t a champion in anything, but I’ve always considered him the essence of the whole thing. He was the most fun skateboarder I’ve ever seen compete in my life because he would just go out and create a disaster. Somehow, out of the disaster, he pulled things off that were impossible that he’d never done before and that he would never do again. It was like seeing a constant series of explosions go off. You never knew what was going to happen, but even though he would fall many times, he always had incredible style and force.

You never knew what was going to happen on or off the skateboard.

Exactly. When we went to the Del Mar contest, we were down there about four days and we used to go to breakfast every morning, either to Denny’s or to this place in Leucadia called Captain Keno’s. One morning at Denny’s, Jay left the table. We were all sitting at the table, eating. It was Stecyk, Skip, Jeff and every team rider, and you can only imagine how crazy that scene was. Anyway, Jay left the table and he disappears and then he comes back and he urges everyone to go into the bathroom, so we all went to see what he’d done now. He had taken a shit in a napkin and then he wiped it all over the bathroom walls. It was everywhere. He had covered the entire Denny’s bathroom with it. That is the kind of stuff that he did all the time without let up. It never stopped. He was like a lightbulb that had too much electricity coming through it and he had to let off some of that excess.

He was like a 110 bulb charged by a 220.

Totally. I will say one thing. He had such beautiful form. In the days we used to ride banks and bowls and stuff like that, his form and how he carried himself when he skateboarded, even when he was 13 or 14 years old, he understood how to hold his body in the correct posture. It was amazing with his hand positioning and his back knee tucked into his front knee. His understanding of style, at such a young age, was really astounding.

I thought so too.

Jay was really amazing, but nobody could walk cross-foot on a board like Tony Alva. He did it so masterly. He had grown up watching Phil Edwards and all these guys surf, and back then the big thing was the crossover walk. He did that so well at Paul Revere on the banked walls and stuff. It wasn’t a big trick and a lot of guys didn’t do that, but he did it so beautifully.

Right. To jump forward, I’m curious about the transition to G&S for you and how that evolved for everyone from that point as kids. All of a sudden, you all grew up and you and your Zephyr dudes were getting separated. What was that like?

It was the most amazing disappointment I ever had in my life up to that point. You know what’s weird? I was a young kid. I wasn’t a well-educated kid at the time I was on the Zephyr team, but I was smart enough to know how special it was. It was like I had one foot in and one foot out. The one foot in was being a skateboarder/surfer. The one foot out was kind of like being the future filmmaker observer, watching what was going on, and I could tell how valuable and unusual this thing was. When it ended, it didn’t make any sense to me whatsoever. One day we’re all hanging out and we’re all friends. The next day, it was just me, Biniak and Muir left on the Zephyr team. Wentzle, Shogo, Tony, Jay and Baby Paul were suddenly on another team. I remember going to a contest and they were wearing different clothes and they were in a whole different scene. We weren’t hanging out with them. There was no animosity, but it was like, “It’s over. You’re there and we’re over here.” Slowly, Biniak left and went to Sims and then Jim Muir left and I was the last skateboarder left on the Zephyr team. By that time, Skip had left too and the Zephyr shop was not open very often. It was dark a lot of the time and they had very little stock in the shop. It became a ghost town. It was really weird and it was really sad. It was no longer the hangout. You never knew when it was going to be open. With Skip not there, Jeff wasn’t the kind of guy that opened up the shop and hung out all day. That was Skip’s job. He ran the shop and opened up in the morning and he would be behind the counter all the time. Jeff came and went. He was kind of an eccentric character. He shaped boards at nighttime and a lot of times Jeff was out doing stuff. There were rumors that he was hanging out in Hollywood with rock stars, so he just wasn’t around that much. When the whole thing collapsed, he started being around more because he was trying to save his business. I remember going in there one day and having to confront him and say that I had gotten an opportunity that I had to take. I wasn’t going to be like the others and just leave. The other guys just left. They never went to Jeff and said, “Hey, I have another opportunity. I have to leave.” I knew I had to do that and go man to man with him. I did that and it was really hard. I made peace with him and he didn’t yell at me. He was very kind about it. He was very disappointed, but he wasn’t mean about it. He was just really disappointed. I remember one day, around that time, I went to the shop and parked my car in back of the shop. There wasn’t much going on and I was just about to take off to Australia on my first skateboarding trip. I was one of the first American skateboarders to get to go to Australia. Back then, going to Australia was a bigger deal than going to Hawaii or the North Shore. I remember Ronnie Jay confronted me in the parking lot of the Zephyr shop, he got in my face and said, “Man, if I didn’t like you, I’d kick your ass. I’m so jealous that you get to go to Australia. Do you know how bad we wanted a trip like that? Do you know how bad we wanted to get to the North Shore? I’m telling you right now, you better not be an asshole about this. You better go over there and represent us. I don’t want you trashing hotels and making us look bad. You go over there and show them what we’re made of.” He really read me the riot act and put the fear of God in me. When he left, I was shaking in my boots. In my whole life, I’ve never forgotten that talk. He was in my face saying, “You have no idea how lucky you are. We wanted this and you’re getting it, so you better do something with it.” It was really heavy. I carried that with me my whole career. Ronnie Jay and Wayne Saunders were really talented surfers and, in today’s world, they all would have had million dollar sponsorships, but back then, unless you were Gerry Lopez or Reno Abellira, you weren’t going to get anything. Those guys never got what they deserved. You know. You saw a million guys like that. Even Mike Purpus never got what he deserved. They never got anything, but we were the next generation and it started to happen for us. They saw that and it killed them. They were happy for us but, at the same time, they were wondering, “Why didn’t this happen for us?” A few years later, I’m at the Skateboarder magazine awards, I think it was the one that you won, and Shaun Tomson was there and some of the other famous surfers of the time. Shaun Tomson came up to me and said, “Man, you guys are the ones making all the money! We’re trying to make this happen in surfing, but you’re the ones making all the money. There’s not enough money where we are in surfing.” And there wasn’t at that time. Those guys saw what we were doing and they wanted the same thing to happen for them, but their time hadn’t come yet. They tried to do the Bronzed Aussies and all that stuff, but it just didn’t happen. They had the right idea, but the timing was off. It wouldn’t happen until ten years later. They were the first ones and they saw what we were doing and they were like, “Wait a minute. These young skateboarders are traveling all around the world and they’ve got their names on product and they’re making money. Why aren’t we doing that? We are making just as much of an influence in surfing as they are in skateboarding, so why isn’t this happening for us?” I think they had their minds set on that. It was pretty heavy.

That’s interesting. Okay, I want to know about the transition from the Bones Brigade into making films? How did that happen for you?

You mean, why did I leave skateboarding?

Well, yeah. Why did you leave skateboarding and how did you make the transition into being a filmmaker?

Well, I made the first Bones Brigade Video Show and George said it was a huge success and I had to start making another one, so I started making more. What happened is, because I was a skateboarder I was able to hold the camera while I skated and get a lot of shots that had previously been impossible to get. I could skate and hold the camera backwards, or forwards, or upside down and I could skate backwards and have somebody skate towards me. There were producers in Hollywood whose kids rode skateboards and their kids were watching my skate videos, and these producers saw all of these weird shots in my skateboard videos and they couldn’t understand how I was getting them, so they started contacting me and saying, “Hey, how did you do this?” I said, “I shoot these shots from my skateboard.” They didn’t believe me, so I would show them, and then they started hiring me on motion pictures to do what’s called Second Unit work, so I was shooting a lot of the action. I did Thrashin’, which you were in, and then I did Police Academy 4 and then I did Gleaming The Cube, and then I did Hook with Steven Spielberg. I kept getting all of these opportunities as a director and then I did Sk8-TV for Nickelodeon. Then it got to the point where I was either going to stay in skateboarding or I was going into filmmaking and I just decided that it was time to make a change. I had enough knowledge to start moving forward as a filmmaker and I wanted to learn how to tell stories. I didn’t think I could continue making skateboard videos. It was hard making a brand new one every single year. I didn’t feel right taking that much from the well, and I needed more time in between. Then it started getting so busy that George started asking for two films per year and that’s when I started going, “It’s too much.” Then he and I started seeing things differently and we had a different idea of where we wanted to take the company. Tony was moving on and Lance was moving on. I didn’t have it in me to start the whole thing back up again with a new group of guys. I couldn’t duplicate what I’d done and it was time to go. I’d had the best run that I could have possibly had and it was time to give someone else a chance. I’d had enough, so I moved on. That was a big move because I was newly married and filmmaking was no guarantee and my identity was wrapped up in skateboarding. I didn’t even know who I would be if I didn’t walk down the street and see some 14-year-old kid with my name on his chest on a t-shirt. I didn’t know if I was going to have some crisis of confidence or an identity crisis when I left the sport, but I was ready to leave because the sport was changing and it didn’t need me anymore. It was time for other people to have their say.

How was the transition for you after you left skateboarding?

It was fairly easy at first. I started working right away. I didn’t do the things I wanted to do right away, but I was working and making a living. After four or five years of directing television, I started getting really bored and I didn’t like doing it any longer. It was the first time in my adult life that I felt like I was going to work, and I was not liking it. At that time, I was also developing my own projects and I was writing screenplays and creating my own television pilots. I had an editing bay at my house and I was doing my own stuff. I went through seven years of supporting myself through TV and doing my own projects on the side and, in that entire seven year period, I never got one of my projects sold. Every single original project I did at that time eventually ended up in a landfill. It was really disheartening. It was just failure after failure after failure. In 1999, I was like, “I’ve got to make something happen. I can’t keep directing the same kind of TV shows I have been directing. It’s killing me.” That’s when I finally got Dogtown and Z-Boys made. I was able to do something without having a network breathing down my neck and stopping me from everything I wanted to do. Vans produced it and they’re not a production company, they’re a shoe company, so they didn’t know how to get in our way. They gave us the freedom to make the film and let the film be what it wanted to be. Jay Wilson who worked at Vans at the time was the brains behind it and he gave us the money to do it and allowed us to make the film it wanted to be. That reopened the doors for me and let me start doing projects that I wanted to do again. Those seven years before that were hard; very hard.

Once Dogtown and Z-Boys hit, it helped your career, no?

Oh yeah. It didn’t necessarily help me get films approved, but it allowed me to get doors open to meet people and say this is what I want to do. It was easier for me to get Riding Giants approved and get a budget behind it because I had a track record that I could make a documentary film and it could make money. Riding Giants did the same thing. Riding Giants was the very first documentary film that the Sundance Film Festival chose to be the premiere opening night film. Robert Redford chose it to be the opening night film and he actually introduced me when it opened that night. That being the premiere film helped me. Once again I had another film in the theaters and it made money. I had a good track record. I was somebody that people could count on to make a film that made money.

Which is not easy to do.

It’s not easy to do. I’d like to say I own my films, but I don’t. They are all owned by somebody else. When people see my films, they always think I’m making money off the royalties from them, but I don’t make any royalties off of them. I don’t get any points or anything. To make Dogtown and Z-Boys, I worked on it for three years. Craig Stecyk and Agi Orsi and myself were the three principles on that film and I think we each made $40,000 for three years work. That was including Craig giving his photographs to the film and me giving my footage to the film. It was not a money maker for us at all. We are certainly glad we did it though.

Me too. So how do you keep coming up with ideas?