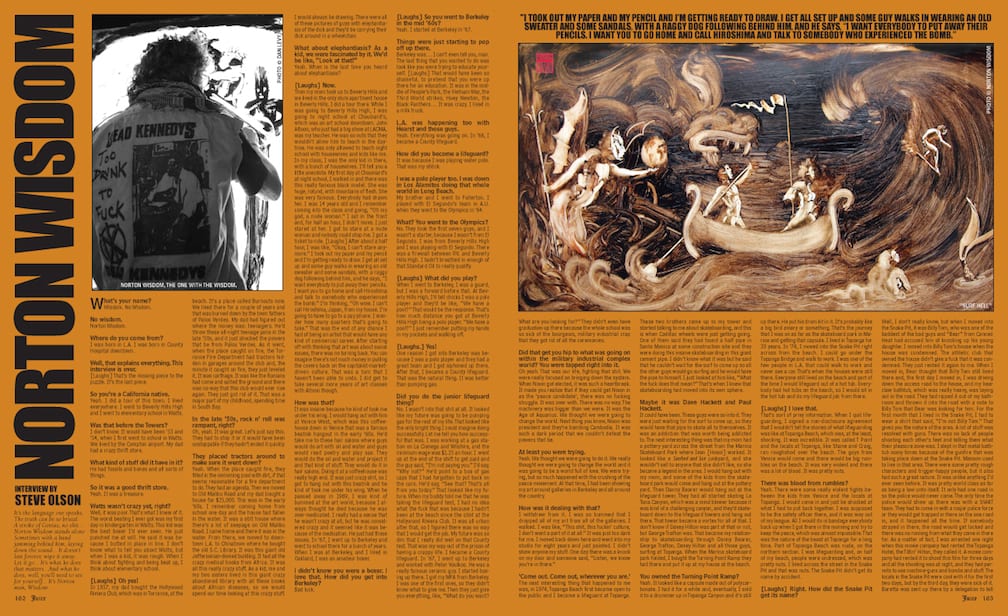

NORTON WISDOM

INTERVIEW & INTRO by STEVE OLSON

PHOTO BY DAN LEVY

ARTWORK BY NORTON WISDOM

It’s the language one speaks,

The truth can be so brutal

A stroke of Genius, no shit…

Norton Wisdom stands alone

Sometimes with a band

jamming behind him, laying down the sound…

It doesn’t last forever, wipe it away…

Let it go… It’s what he does that matters…

And what he does, well, you’ll need to see for yourself…

It’s Norton man, Wisdom …

What’s your name?

Wisdom. No Wisdom.

No wisdom.

Norton Wisdom.

Where do you come from?

I was born in L.A. I was born in County Hospital downtown.

Well, that explains everything. This interview is over.

[Laughs] That’s the missing piece to the puzzle. It’s the last piece.

So you’re a California native.

Yeah. I did a tour of this town. I lived everywhere. I went to Beverly Hills High and I went to elementary school in Watts.

Was that before the Towers?

I don’t know. It would have been ’53 and ’54, when I first went to school in Watts. We lived by the Compton airport. My dad had a crazy thrift store.

What kind of stuff did it have in it?

He had fossils and bones and all sorts of things.

So it was a good thrift store.

Yeah. It was a treasure.

Watts wasn’t crazy yet, right?

Well, it was poor. That’s what I knew of it. The worst beating I ever got was my first day in kindergarten in Watts. This kid was the best boxer I’d ever seen. He just punched me at will. He said it was because I butted in place in line. I don’t know what to tell you about Watts, but when I was a kid, it was rough. When I think about fighting and being beat up, I think about elementary school.

[Laughs] Oh yes!

In 1957, my dad bought the Hollywood Riviera Club, which was in Torrance, at the beach. It’s a place called Burnouts now. We lived there for a couple of years and that was burned down by the town fathers of Palos Verdes. My dad had figured out where the money was: teenagers. He’d throw these all-night teenage jams in the late ‘50s, and it just shocked the powers that be from Palos Verdes. As it went, when the place caught on fire, the Torrance Fire Department had tractors hidden in garages around the club and, the minute it caught on fire, they just leveled it. It was Carthage. It was like the Romans had come and salted the ground and there was no way that this club would ever rise again. They just got rid of it. That was a major part of my childhood, spending time in South Bay.

In the late ‘50s, rock n’ roll was rampant, right?

Oh, yeah. It was great. Let’s just say this. They had to stop it or it would have been unstoppable if they hadn’t ended it quickly.

They placed tractors around to make sure it went down?

Yeah. When the place caught fire, they filled in the swimming pool with dirt, if that seems reasonable for a fire department to do. They had an agenda. Then we moved to Old Malibu Road and my dad bought a house for $25,000. This was in the early ‘60s. I remember coming home from school one day and the house had fallen in the water. It was a stilt house where there’s a lot of seepage on Old Malibu Road. I came home and there it was in the water. From there, we moved to downtown L.A. to Chinatown where he bought the old S.C. Library. It was this giant old Jeffersonian-domed building. It had all the crazy medical books from Africa. It was all this really crazy stuff. As a kid, me and my two sisters lived in this giant crazy abandoned library with all these books about African diseases, so we would spend our time looking at this crazy stuff. I would always be drawing. There were all of these pictures of guys with elephantiasis of the dick and they’d be carrying their dick around in a wheelchair.

What about elephantiasis? As a kid, we were fascinated by it. We’d be like, “Look at that!”

Yeah. When is the last time you heard about elephantiasis?

[Laughs] Now.

Then my mom took us to Beverly Hills and we lived in the only slum apartment house in Beverly Hills. I did a tour there. While I was going to Beverly Hills High, I was going to night school at Chouinard’s, which was an art school downtown. John Altoon, who just had a big show at LACMA, was my teacher. He was so nuts that they wouldn’t allow him to teach in the daytime. He was only allowed to teach night school with housewives and kids like me. In my class, I was the only kid in there, with a bunch of housewives. I’ll tell you a little anecdote. My first day at Chouinard’s at night school, I walked in and there was this really famous black model. She was huge, rotund, with mountains of flesh. She was very famous. Everybody had drawn her. I was 14 years old and I remember coming into the class and going, “Oh my god, a nude woman.” I sat in the front and, for half an hour, I didn’t move. I just stared at her. I got to stare at a nude woman and nobody could stop me. I got a ticket to ride. [Laughs] After about a half hour, I was like, “Okay, I can’t stare anymore.” I took out my paper and my pencil and I’m getting ready to draw. I get all set up and some guy walks in wearing an old sweater and some sandals, with a raggy dog following behind him, and he says, “I want everybody to put away their pencils. I want you to go home and call Hiroshima and talk to somebody who experienced the bomb.” I’m thinking, “Oh wow. I can’t call Hiroshima, Japan, from my house. I’m going to have to go to a pay phone. I wonder how many quarters that’s going to take.” That was the end of any chance I had of being an artist that would have any kind of commercial career. After starting off with thinking that art was about social issues, there was no turning back. You can imagine there’s not much money in pulling the covers back on the capitalist-market-driven culture. That was a turn that I haven’t been able to undo. I did get to take several more years of art classes with Altoon though.

How was that?

It was insane because he kind of took me under his wing. I would hang out with him at Venice West, which was this coffeehouse down in Venice that was a famous beatnik hangout in the early ‘60s. He’d take me to these hair salons where guys would do art with oil and water and guys would read poetry and play sax. They would do the oil and water and project it and that kind of stuff. They would do it in hair salons. Doing it at a coffeehouse was really high end. It was just crazy shit, so I got to hang out with this beatnik and he kind of took me under his wing. When he passed away in 1969, I was kind of bummed at the art world, because I always thought he died because he was over-medicated. I really had a sense that he wasn’t crazy at all, but he was considered crazy and it seemed like it was because of the medication. He just had those issues. In ’67, I went up to Berkeley and went to school there for a bunch of years. When I was at Berkeley, and I lived in Oakland, I was an amateur boxer.

I didn’t know you were a boxer. I love that. How did you get into Berkeley?

Bad luck.

[Laughs] So you went to Berkeley in the mid ‘60s?

Yeah. I started at Berkeley in ’67.

Things were just starting to pop off up there.

Berkeley was… I can’t even tell you, man. The last thing that you wanted to do was look like you were trying to educate yourself. [Laughs] That would have been so shameful, to pretend that you were up there for an education. It was in the middle of People’s Park, the Vietnam War, the Third World strikes, Huey Newton, the Black Panthers… It was crazy. I lived in a milk truck.

L.A. was happening too with Hearst and those guys.

Yeah. Everything was going on. In ’66, I became a County lifeguard.

How did you become a lifeguard?

It was because I was playing water polo. That was my shtick.

I was a polo player too. I was down in Los Alamitos doing that whole world in Long Beach.

My brother and I went to Fullerton. I played with El Segundo’s team in A.U. when they went to the Olympics in ’64.

What? You went to the Olympics?

No. They took the first seven guys, and I wasn’t a starter, because I wasn’t from El Segundo. I was from Beverly Hills High and I was playing with El Segundo. There was a firewall between P.V. and Beverly Hills High. I hadn’t breathed in enough of that Standard Oil to really qualify.

[Laughs] What did you play?

When I went to Berkeley, I was a guard, but I was a forward before that. At Beverly Hills High, I’d tell chicks I was a polo player and they’d be like, “We have a pool?” That would be the response. That’s how much distance you got at Beverly Hills High being a polo player. “We have a pool?” I just remember putting my hands in my pockets and walking off.

[Laughs.] Yes!

One reason I got into Berkeley was because I was a polo player and they had a great team and I got siphoned up there. After that, I became a County lifeguard. That was the natural thing. It was better than pumping gas.

Did you do the junior lifeguard thing?

No. I wasn’t into that shit at all. It looked like my future was going to be pumping gas for the rest of my life. That looked like the only bright thing I could imagine doing successfully. Let me tell you how successful that was. I was working at a gas station on La Cienega and Wilshire, and the minimum wage was $1.25 an hour. I went up at the end of the shift to get paid and the guy said, “I’m not paying you.” I’d say, “Why not?” He’d point to a box of gas caps that I had forgotten to put back on the cars. He’d say, “See that? That’s all from you today.” That looked like my future. When my buddy told me that he was taking the lifeguard test, I had no idea what the fuck that was because I hadn’t been at the beach since the stint at the Hollywood Riviera Club. It was all urban after that, so I figured there was no way that I would get the job. My future was so dim that I really did well on that County test. That was my way out of the prison of having a crappy life. I became a County lifeguard. In ’67, I went up to Berkeley and worked with Peter Voulkos. He was a really famous ceramic guy. I started boxing up there. I got my MFA from Berkeley. I was one of the first ones, so they didn’t know what to give me. Then they just give you everything, like, “What do you want? What are you looking for?” They didn’t even have graduation up there because the whole school was so sick of the bourgeois, military industrial crap that they got rid of all the ceremonies.

Did that get you hip to what was going on within the military industrial complex world? You were tapped right into it.

Oh yeah. That was our life, fighting that shit. We were really focused on bringing down the system. When Nixon got elected, it was such a heartbreak. It made you realize that if they could get Nixon in as the ‘peace candidate’, there was no fucking struggle. It was over with. There was no way. The machinery was bigger than we were. It was the Age of Aquarius. We thought we were going to change the world. Next thing you know, Nixon was president and they’re bombing Cambodia. It was such a dark period that we couldn’t defeat the powers that be.

At least you were trying.

Yeah. We thought we were going to do it. We really thought we were going to change the world and it was going to be a world full of love. We were trying, but so much happened with the crushing of the peace movement. At that time, I had been showing my art around galleries in Berkeley and all around the country.

How was it dealing with that?

I withdrew from it. I was so bummed that I dropped all of my art from all of the galleries. I walked. I was like, “This shit, this fuckin’ culture, I don’t want a part of it at all.” It was just too dark for me. I moved back down here and went into my studio for eight years and just painted. I didn’t show anyone my stuff. One day there was a knock on my door and someone said, “Listen, we know you’re in there.”

‘Come out. Come out, wherever you are.’

The next interesting thing that happened to me was, in 1974, Topanga Beach first became open to the public and I became a lifeguard at Topanga. These two brothers came up to my tower and started talking to me about skateboarding, and this is when Cadillac wheels were just getting going. One of them said they had found a half pipe in Santa Monica at some construction site and they were doing this insane skateboarding in this giant cement pipe. I didn’t know what it was but he said that he couldn’t wait for the surf to come up so all the other guys would go surfing and he would have the pipe to himself. I just looked at him like, “What the fuck does that mean?” That’s when I knew that skateboarding had moved into its own sphere.

Maybe it was Dave Hackett and Paul Hackett.

It could have been. These guys were so into it. They were just waiting for the surf to come up, so they would have that pipe to skate all to themselves. It was an addiction that was worth being addicted to. The next interesting thing was that my mom had a pottery yard across the street from the Marina Skateboard Park where Ivan [Hosoi] worked. It looked like a Sanford and Son junkyard, and she wouldn’t sell to anyone that she didn’t like, so she became a legend in the area. I would hang out with my mom, and some of the kids from the skateboard park would come and hang out at the pottery yard. Then Danny Bearer would hang out at the lifeguard tower. They had all started skating La Tuna Canyon, which was a mind blower because it was kind of a challenging canyon, and they’d skateboard down to the lifeguard towers and hang out there. That tower became a vortex for all of that. I don’t know if Davey Hilton was part of that or not, but George Trafton was. That became my relationship to skateboarding through Danny Bearer, George Trafton, Davey Hilton and all those guys, surfing at Topanga. When the Marina skateboard park folded, I bought the Turning Point Ramp they had there and put it up at my house at the beach.

You owned the Turning Point Ramp?

Yeah. It looked like a capsule made out of polycarbonate. I had it for a while and, eventually, I sold it to a drummer up in Topanga Canyon and it’s still up there. He put his drum kit in it. It’s probably like a big bird aviary or something. That’s the journey that I was on as far as the skateboard park in Marina and getting that capsule. I lived in Topanga for 30 years. In ’74, I moved into the Snake Pit right across from the beach. I could go under the Topanga Bridge and walk to work. I was one of the few people in L.A. that could walk to work and never see a car. That’s when the houses were still there. Everyone still lived on the beach and part of the time I would lifeguard out of a hot tub. Everybody had hot tubs on the beach, so I would sit in the hot tub and do my lifeguard job from there.

[Laughs] I love that.

That’s sort of privy information. When I quit lifeguarding, I signed a non-disclosure agreement that I wouldn’t tell the stories of what lifeguarding was like at Topanga Beach, which was, at the least, shocking. It was incredible. It was called T Point and the locals at Topanga, like Shane and Craig, ran roughshod over the beach. The guys from Venice would come and there would be big rumbles on the beach. It was very violent and there was a lot of blood. It was pretty nuts.

There was blood from rumbles?

Yeah. There were some really violent fights between the kids from Venice and the locals at Topanga. I would come in and just be shocked at what I had to put back together. I was supposed to be the safety officer there, and it was way out of my league. All I would do is bandage everybody back up when I got there in the morning and try to keep the peace, which was almost impossible. That was the nature of the beast at Topanga for a long time. Part of Topanga Beach was nude, on the northern section. I was lifeguarding and, on half of my beach, people were undressed, which was pretty nuts. I lived across the street in the Snake Pit and that was nuts. The Snake Pit didn’t get its name by accident.

[Laughs] Right. How did the Snake Pit get its name?

Well, I don’t really know, but when I moved into the Snake Pit, it was Billy Tom, who was one of the baddest of the bad guys and “Bear” from Canned Heat had accused him of knocking up his young daughter. I moved into Billy Tom’s house when the house was condemned. The athletic club that owned the house didn’t give a fuck that it was condemned. They just rented it again to me. When I moved in, Bear thought that Billy Tom still lived there and, the first day I moved in, I was driving down the access road to the house, and my bear claw bathtub, which was really heavy, was laying out in the road. They had ripped it out of my bathroom and thrown it into the road with a note to Billy Tom that Bear was looking for him. For the first month that I lived in the Snake Pit, I had to wear a shirt that said, “I’m not Billy Tom.” That gives you the nature of the area. A lot of stuff was resolved with guns. There was no lack of people shooting each other’s feet and telling them what their pleasure zone was. I slept in that metal bathtub many times because of the gunfire that was taking place down at the Snake Pit. Manson used to live in that area. There were some pretty rough characters and trigger-happy people, but it also had such a great nature. It was unlike anything I’d ever seen before. It was pretty world class as far as being a law unto itself. It only had one road in so the police would never come. The only time the police would show up there was with a SWAT team. They had to come in with a major police force or they would get trapped in there on the one road in, and it happened all the time. If somebody strayed in there, the road would get locked and there was no running from what they came in there for. As a matter of fact, I was arrested one night when this movie company had rented the Topanga Hotel, the Tiltin’ Hilton, they called it. A movie company had rented it to shoot this film for three days and all the shooting was at night, and they had permits to use machine-guns and bombs and stuff. The locals in the Snake Pit were cool with it for the first two days, but by the third day, they were sick of it. Baretta was sent up there by a delegation to tell the director of the film that the locals couldn’t sleep, so maybe if you gave them $300 and bought everyone some booze, they could have their own party, and you could shoot your film. The lady said, “Okay, come back in an hour and we’ll have your money for you.” When we came back, the cops were there, and they were like, “That’s extortion, so if we see you around here again, we’re going to put you in jail. Get the fuck out of here.” Baretta went back and told the locals and they said, “Oh, really?” That night when the movie company started filming and shooting off their weapons, the local people put their car alarms up in trees where you couldn’t get to them. Then they started shooting tomatoes at them with those huge rubber band launchers that shoot 100-feet and they just shut down the movie production crew. Then the sheriffs came. I wanted to participate in this, but I had a gig that night. I felt embarrassed that I wasn’t going to be part of the team dealing with this movie issue, so I gave them $50. I said, “Go buy some tomatoes to use as missiles.” I threw some money into the pot and then I went to my gig. I didn’t think too much of it. When I came back, I heard that all the locals had their stereos up loud, so the movie crew couldn’t do any audio recording. I was just returning to the scene of the crime after doing my gig in Hollywood, so I decided to join the fun. I had this 300-watt amp and these huge 15-inch bass speakers, and I lived right beside the Reel Inn where they were shooting the movie, so I put my speaker out on my patio and I played the only song that I’ve ever written that I was proud of, “I Hate The Rich!” I started singing it with this huge amp and, the next thing I know, there’s a sheriff on my patio. He stuck his head into the speaker just as I was screaming “Hate!” and it knocked him back on the ground. He was flat on the ground and then he got up and ran away. I was feeling pretty invincible by then and, the next thing I know, two other sheriffs came into the yard and threw me on the ground and handcuffed me and put me in the back of the squad car. Larry Payne, one of my crazy neighbors, was also arrested for trying to tell them that I had been in Hollywood and I wasn’t a big part of this event, and then he was in handcuffs, too. They charged me with the crime of “assault on an officer with sound beyond the threshold of pain.” It was kind of a serious charge. Because I was a County lifeguard, the D.A. threw it out, but it was brought right up to the edge of trial. I was put in jail for the night, and of course, I knew everyone in the holding tank. That’s what the Snake Pit was about. It was a law unto itself and I lived there for 30 years.

Nice. What happened in the ‘80s? Tell me about your Berlin Wall project.

In the early ‘80s, I started being offered all these shows. All of a sudden, I had these big shows in L.A. In 1981, I went to Germany and I was showing in Germany too. Reagan was just elected and Reagan decided he was going to save Germany from the Russians by neutron bombing them. The Germans got all upset about this because, even though none of the buildings would be destroyed by a neutron bomb, everybody would be dead, so they had this huge march. It was like 300,000 people, which then was as big as it got. I was there, in Munich, with Werner Herzog, one of your German artists. I was having dinner with him and this great German sculptor, Nicoli Tragor. We decided that we couldn’t just sit on the sidelines as erudite artists and watch this big mass movement against American imperialism and militarism, so we decided we were going to go to Berlin when they were marching. I was going to paint on the Berlin Wall and this German sculptor was going to do a bas-relief carve on it and Werner Herzog was going to auction it off on cable TV. He had just made some big film and he was the celebrate independent filmmaker. He was being lauded as saving cinema. We’re having dinner and we were talking about doing this big project on the Berlin Wall to make our statement as artists. We weren’t going to sit on the sidelines. Werner had just come back from Aspen where his film had won the Aspen Film Festival and he was top of his game. The film was with Mick Jagger.

Was it Performance?

No. It was the one about the opera house in Brazil, Fitzcarraldo. Werner was all puffed up and he was with his Italian girlfriend and we were eating dinner, and she was so fucked up on heroin that she couldn’t even keep her face out of the pasta. I was trying to talk to him and keep an airway for his girlfriend, while we made plans to go to Berlin the next day. Then he goes, “You know, my favorite American is this guy, Dirty Harry.” Dirty Harry was this guy that would sit in the alleys of New York, in a trench coat and, when chicks would walk by, he would expose himself and then he would interview them, right?

Yeah.

He just thought this Dirty Harry guy was amazing. I thought the guy was kind of a jerk, but no big deal. I just said, “I don’t really know a lot about him.” Werner got so pissed off at me. He just started yelling, “You’re stupid! You don’t know anything about your people, or American culture!” He just went off the deep end. He was leaning on me and I was like, “What the fuck, man?” I looked at him as he’s yelling at me and I said, “Nice belt.” He had this big cowboy belt on with a big buckle. He goes, “Yeah. They gave this to me in Aspen. This is real cowboy shit.” I’m looking at it and it had an engraving of this guy Heinrich Kley, who was a very famous German academic drawer at the turn of the 20th Century. I said, “Wow. That’s pretty interesting that they would put a German artist on your cowboy belt.” He goes, “You pig! This is real cowboy!” He went nuts and I couldn’t bring him back down, so that whole plan fell apart…

[Laughs.] Over the cowboy belt and Dirty Harry.

Yeah. Then I had a mural I was going to do at this castle in the Black Forest, so I went there to do it, and I had taken some L, and I went for this big five-hour run with the elves and the toadstools in the Black Forest. At the end of it, I had this Gestalt kind of flash of, “Do what you do best, but do it on the Sistine Chapel.” I was coming out of the light and the trees and the sun, and I’m thinking, “What the fuck does that mean? Do what you do best. I’m an abstract painter, that’s what I do, but what’s the Sistine Chapel?” The Sistine Chapel was the division between the Renaissance and the Middle Ages and also between the Christian world and the Pagan world. Michelangelo had put a lot of pagan gods in “The Last Judgment” with Christ and the gods, so it was a wall between good and evil and the two big worlds of dark and light. I was like, “Okay, that’s the Berlin Wall.” So I’m back on the project. I went by myself to Berlin and you couldn’t even touch the wall on the West side of the Berlin Wall in 1981, so I had to jump over into the East Side. I had to stay there for three days because once I left the wall, I couldn’t get back over. It was a funny part of the wall in a place called Wedding. It was in the Turkish slums, so they didn’t really care. I did this 150-meter mural of these trapezoids on the Berlin wall, and when I jumped back over, I was arrested by the West Berlin police for leaving without a visa, and I was flown out of Berlin. When I came back to L.A., I couldn’t go back in my studio after that, when the world was so volatile. At that time, the drummer from Iron Butterfly was hanging out in my studio and he’d bring his drums and he’d play while I was painting. This was at my studio on Crenshaw and La Brea. I had a big studio there. He’d come by with some other musicians and hang out and then we were like, “Let’s bring this to the rest of the world.” So we started a band called Panic and we’d play in all the punk clubs. In ’81, we were playing at Cathay de Grande, Helen’s and Madame Wong’s… In the art world, at this time, we were doing the New Wave Theatre…

I remember the conspiracy of the murder.

Exactly. Peter Ivers. Out of all the bands and musicians I’ve performed with, Panic was the craziest shit ever. The art world, and the captains of culture pulled me aside and said, “This is stupid. If you do this, we are going to turn our back on you.” I was like, “Yeah. Right. This has nothing to do with you.” And then I was dropped immediately. I couldn’t believe it. I went from being an artist that would give stuff to benefits and then they would sell your stuff and let you go to the party. From then on, I couldn’t even give my stuff to the benefits. If I said, “Oh, hey, are you having a benefit and a party?” They’d say, “Well, you have to submit your work to a jury and they’re going to decide if we will even take your stuff to auction it off. You get nothing of course, but you can’t just give it to us.” That’s how gnarly the cold shoulder I got was, in the early ‘80s, because I was painting in this punk band. It was bizarre how angry they got about it. Llyn Foulkes, with his one-man-band, experienced the same thing. They just couldn’t stand it. They can’t stand anyone having a dual commitment to aesthetics. They wanted it all to be pigeon-holed. Plus, music… To them, it was like, “How disgusting.”

That’s lame.

I was shocked. I couldn’t believe that they were really serious about it. That was the end of my thing for another ten years. Then another gallery knocked on my door and said, “Who’s in there?” And I started showing again.

Isn’t it just about the process anyway?

That’s what it was, yes, but I didn’t just want to be a famous painter, I wanted to be a great painter. I figured it would take me at least ten years to learn how to paint oil paintings. Oil was such a crazy mysterious material that I thought it was going to take a long time to figure out how to paint with it.

You were a lifeguard at the same time.

Yeah. I didn’t need the art world. I had my own world. I was totally indifferent to their indifference, and to society itself. I had my little shtick with the lifeguards, which was all I needed. I had the beach and I had my studio. My life was full and I was really content. The tough stuff is when you kind of get involved with the art world and the stupidity of it and the childishness of it. It’s these people that are all about the People Magazine photo ops at the openings with their back turned to the art. When you look at that, it’s such childish shit, that you can’t really get too worked up about it.

You can’t give a fuck about that.

You get sucked up a little bit, like, “I should be involved. I should participate.” But when you look at it, it seems so shallow.

I did a thing with Shepard Fairey in New York, and I did a thing kind of against their whole world and he showed up and said, “Your presentation is kind of weak. You should probably work on that.” I told him, “Oh, you’re missing the point, again.” It was the best.

[Laughs] It’s amazing. You threatened the status quo, and he’s part of the status quo now. They have an army of critics and writers to protect them. Their job is to protect the status quo and the market. It’s like Mark Ryden. Did you see his show?

No.

He had a big show in L.A. and the L.A. Times so viciously attacked it that art critics that I respect, who don’t particularly like Mark Ryden because he’s popular and he doesn’t need the art world at all, said, “These vicious dogs don’t need to be so mean about Mark Ryden. You shouldn’t be that mean about any human being.” The art world is so threatened by people that don’t need them or can go around them that their wrath is furious.

You experienced it firsthand.

Yeah. I’m sure you have. I’m sure you’ve seen the indifference and how they marginalize people that aren’t part of the marketplace. It’s ruthless and relentless.

Recently, I’ve come to agree completely with everything that you’ve said. You don’t need the art world. If you’re making art, you’re making art. If you’re making art to be accepted by these people, you have a problem already. You make the art for yourself and because you want to make it or you have to make it. Then you have succeeded.

They can only cheat you out of the passion that you have for making art. They can only make you lose the real desire to make it by looking over your shoulder and saying what they think of it. It just drains the blood out of it.

Unless you say, “Who gives a fuck what they think?” That really makes them mad.

There was a really great statement about art critics by Barnett Newman. “Artists need critics like birds need ornithologists.” To me, I’m the bird and they’re like ornithologists. They’re staring at me and I’m just wondering, “Who are these people with their clipboards?” I just look at them, kind of baffled, and then I just fly away. They just mean nothing. You can call them idiots because you look at what they write. I’m calling them idiots.

Well, I’ll continue to call them idiots, but they’re not dumb.

They are dumb. If you look what they write, it’s absolutely valueless. They say nothing of value. It’s all about how many paintings are in the show and whether they are hung well and who the director is and the curator was. When you look at the ideas behind the art, there’s nothing in there. If you follow the art criticism that we are given in this town, there is no depth to it. It’s so superficial on things that don’t really unlock the works of art to the public. They don’t give anybody a portal to what the artist is trying to do or what its value is or inspire anybody to make art. I can’t imagine these people inspiring anybody to make art.

I don’t hang out with those people.

I feel sorry for young kids that are trying to navigate their way and find out how they should live their life. It’s a dangerous thing.

I find it absurd that they’d go against you doing painting and music in a punk band. Punk was a great movement on its own.

Now punk is being realized as one of the really authentic movements in culture. It saved us from disco. If it wasn’t for the punk movement, we’d be doing the hustle right now at the Factory. Life would have been pretty grim if punk rock hadn’t brought back sincerity and gotten rid of the commodities. [Laughs]

[Laughs] Yeah.

I’m lucky enough to have hooked up to the punk world in the early ‘80s with guys like Nels Cline. We used to play at the Tourist Tavern, which was a dike biker bar across from the Comeback Inn. That was on Washington, which is now called Abbott Kinney. There was a hippie bar there and a dike biker bar. Nels is a god in the free music world. He’s a guitarist in a band called Wilco now. As a kid, he would come to this dike biker bar and sit outside the door. We had Baretta, who was kind of a thickster, kind of a thug, and he was at the door to collect $5 from anyone that came in to listen to us. We’d say, “Okay, Baretta, how much did we make?” And he’d say, “I was afraid to ask anyone for money.” We’d go, “What?” He’d point at the bar, and everyone at the bar looked like they had just stepped out of a Dick Tracy magazine. Every Dick Tracy character was in the bar.

Do you remember that band Crime from S.F. in the late ‘70s? They looked like Dick Tracy, but in leather.

I’m sure I knew them because I knew Spyder Mittleman who was in the Whirling Butt Cherries. He was part of that whole scene, and I used to hang with him and do stuff with him and James Mathers. He was another guy that was pretty thick in that crowd. I’m sure I know Crime.

They were great.

You probably wouldn’t ask them to pay at the door to get in either, huh?

No. You would think, “They might kill us for that.”

We were right across from Brandelli’s Brig, which, at that time, wasn’t a yuppie hang out. It was Brandelli’s Brig, and you had that crowd and these dike bikers. I made a lot of good music connections there. That’s where I eventually hooked up with Mike Watt and Banyan. I went from that and then I started performing with Nels Cline who had New Music Mondays with all the free jazz musicians that couldn’t get gigs anywhere else. He had this place at the Alligator Lounge in Santa Monica where they could play, so I started playing with Nels and his band. Then he started playing in a band called Banyan with Steve Perkins and Mike Watt, and he brought me into that. In the late ‘90s, I started playing with Banyan and then we started touring.

How was that?

It was great. My first tour with Banyan, they showed me the bench seats in the van. They said, “This is our car.” I didn’t know any athlete that could get into that car. They’d just load it up and go for weeks riding the bench seats with all their musical instruments. It was a slave ship. It was basically the middle passage. It was no problem for those guys. Musicians are the toughest. There are no pussies there.

When you’re traveling, that’s a hard road.

Yeah. You play until 2:00am. By the time you’re loaded out, it’s 3:30am. At 4 o’clock in the morning, you’d get to go to the hotel. The “grand poobah” would get a room and the rest of us would sleep on the floor in the other room. Watt insisted on the floor. You’d think that his stature would give him a bed and he’d be like, “I sleep on the floor.” I’m like, “What? People are going to walk over you.” He’d be like, “I sleep on the floor.” There is nobody tougher than Mike Watt. There is no water boarding or anything you could do to this guy to impress him. At six o’clock in the morning, you’d be in the van driving all day to get to the next gig. It went on for weeks. It made a man out of you. The music was brilliant. It was all improv and tough as nails. Perkins is one of the great drummers. Willie Waldman was the trumpet player out of Memphis. I used to carry mace with me to protect me from the band. I’m not talking about the mace you buy at the supermarket. I’m talking about the heavy duty mace I could buy as a lifeguard. This was for bear, and still it was shaky. It wasn’t like I never pulled it out. My finger was on the flip-switch most of the time. The music was brilliant and I got to see this country. I got to tour the country and see the South. We went to crazy places and I got to go to Fargo, North Dakota and Jackson, Mississippi. We went places that you just can’t get to. These people are like out of a museum in some of these places. In the middle of it, there’s an amazing heart beating. Outside of it, there’s this craziness. You can’t get there unless you’re touring with a band. There’s just no access to it.

Do you prefer what you’re doing now to when you were doing the gallery scene?

Absolutely. My dealer right now is Robert Berman, who has a great heart and he’s socially committed. He’s probably not loved by the art world. He’s probably kind of a black sheep. At best, they put up with Robert Berman, but I really like where he stands politically. He’s really progressive and he fights the fight. I love Berman. I was in this show downtown in Chinatown that you were at with the California Locos with John Van Hamersveld, who is the coolest, along with Dave Tourje, Gary Wong and Chaz Bojorquez, the grandfather of street art. I’m running with guys like you, and that makes it really wonderful. It’s not the People Magazine art world, where you’re trying to give your recipe for blueberry pancakes to the art critic. There’s a great thing to be said about that. As far as being a commercial avenue, there is nothing there. There is no money. The real wealth in this town is not involved with that. We’re not creating commodities that we can push back and forth and push the price up and not ever have to see them. They just have their agent bring it to the warehouse and then they put it up for auction and they never even have to see the stuff they are trading. It’s better that they don’t, because then they would have to be responsible for the stuff they’re trading. You look at Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst and you have to say that they are really hanging crap and shit on their museum walls and, hopefully, Damien and Jeff are hip enough to laugh about what they’re doing.

I think they both are. They’ve got to be.

They’ve played it to the hilt and these people have followed blindly. First of all, the only really bad thing about it is what it’s teaching young artists. It’s teaching young artists that this is what art is all about. It’s just making ideas without your soul in it or any stamp of your personality in it, without any latch onto the world you live in. What these captains of culture are presenting as art has nothing to do with the world we live in. You couldn’t extract the every day world that we live in from these works of art. There’s just nothing in there. It’s an idea and concepts and commodity. It’s sad to do to young artists. We’ve lived through it and we see the folly and we’ve survived. We don’t need it. Our world is independent of that kind of crap. It’s like the bird watching the ornithologist. We can just look at it and see these people with their clipboards. When you go to an art show, you can tell who the real power brokers are because they have their back to the art. That’s how you can really size up people at an art opening, and who the real power is.

Wouldn’t it be really great to actually do a show and then handpick people that you wanted kicked out? Have a guy like Baretta who isn’t afraid to ask for the $5 at the door, but would really like to throw people out anyway.

Yeah. The thing about it is those people wouldn’t come to art shows. The ones we’d want to kick out, won’t come to our art shows. That’s the riddle. If they did, it would be great to kick them out.

Oh, it would be so great to say, “Oh, no. You can’t look at this.”

Well, we’ve already done it symbolically with what we make. We already kicked them out by putting the humanity in our pieces. They can’t get past the velvet rope because inside there is an indictment of who they are and the games they’ve played. We’ve done it. We’ve already kicked them out in the best way possible. Our art will remain and will always be an indictment against them. Not only have they already been kicked out, but our art will always follow them like, “You didn’t get in.” No matter how much money they have or how isolated they can make themselves in their gated community, there are people out there making art that holds them accountable for their crimes.

That’s a weird one though because you deal with people that don’t know or just don’t understand. I like when people say, “You had a show. Did you sell anything?” They don’t ask how the art looked or how the response was to it.” They just want to know if you sold out the show. It’s a joke. It’s like, “Did you look at it at all?”

It’s baffling. I have a work for Juice and it was this piece of art that Mike Watt had signed. I showed it to an art critic, and she didn’t even look at the piece. She just said, “How much?” I was baffled. This is a person that you would think would look at it at least. That idea of “How much did you sell?” Immediately, you know what you’re dealing with. They have exposed themselves. You own them because you know who they are and you can just push them out of the way.

Someone asked me how much a piece of mine was selling for and I said, “$250,000.” They said, “What?” I said, “Yeah. If I dropped a zero, it would be half of your financial security.”

That’s the only thing they understand. “You’re not rich enough.”

That’s so bitchin’. That is the best thing to ever pull off. “You can’t afford it.”

Yeah. You’re out of the loop. You had your one shot at it. It’s a great victory in being yourself.

I just said that to a guy that really liked one of my pieces. You could tell his passion for it. He thought it was the greatest thing and he got the passion behind it. Everything he liked about it was spot on, so I just gave it to him. He got the intrinsic value of it and it was bitchin.

The piece lives now. It’s great when it finds the right home.

It’s perfect. Okay. Wait. Was Ivan Hosoi at Berkeley when you were at Berkeley?

Yes. One of the biggest influences on my art in my life was Ivan Hosoi, Christian’s father. I didn’t know him that well when I was going to Chouinard, but he went up to Berkeley and he was already up there when I got there. He became a real inspiration. He brought this sort of Japanese sensibility and concentration to art and aesthetics and how every aspect and every element of art was something that had to be considered. When he would draw on paper, he would paint the white paper white first. It wasn’t just that he was drawing on white. He was drawing on his white. Every aspect was essential to him. That blew my mind. I had no idea that every aspect of what you make creatively, you’re responsible for. To me, Ivan was probably the most influential guy in my art, and the most elegant and well-spoken. Without him, I can’t imagine finding much value in art. He was a turning point to realizing how significant every little aspect is. Ivan moved back to L.A. after the Berkeley years, and I would visit him when Christian was a kid. I used to hang out with the family when they lived in this big Victorian house in central L.A. I got to know Christian as a kid pretty well. Ivan’s wife’s name was Bonnie, and she was a beautiful lady. Eventually, Ivan and I went on our different paths. Then one day I ran into Ivan and I said, “What’s going on in the art world? What are you making?” He said that he had stopped making art. He found what was more important than making art. He was one of the first ones to see that art had gone in this foolish direction, so he was devoting his life to his son and skateboarding. He had gotten a job in the Marina Skateboard Park and was totally focused on his son and his son’s expression as an artist in skateboarding. I still have never heard of anything like it. He and his son had become sort of a single work of art using skateboarding as the vehicle for this expression. At the time, it was baffling. There’s not many instances when a father and son become a force in an expression of art. He realized that the most important thing in life is not your own personal fame or celebrity, but getting behind something that was truly beautiful.

The fact that he did that for his kid is amazing. So you did 30 years in the Snake Pit in Topanga. What happened then?

Well, Gray Davis had received a huge bankroll from the athletic club to run his gubernatorial campaign and his payback was that he was going to buy all the property around the Snake Pit, because they couldn’t sell it. Most of the property was condemned and nobody could build on it. They were stuck with it because it was located in a flood zone. They came up with this phony scam that the state was going to buy it and turn it into a park. The state had no money to put in a park, but that was how they paid back the athletic club for financing Gray Davis’ campaign. They gave us huge bags of money to move out. I lived down there for free, basically. By the time I moved in, all the meters had been pulled and bypassed, so all the utilities were free. We had our own TV station down there. It was pretty much like the frontier. After 30 years of paying a couple of hundred dollars rent for as much property as one could fence in, we got a big bag of money to move out. It just shows you how stupid government is. If you do live on the fringe, the system is a joke. It defeats itself. The system is actually quite stupid. I can’t really go on to what else I do to defeat the system, and to not pay for wars, but I’m pretty devoted to not paying for anything that goes into the military. I refuse to pay for anything that this country does militarily. It’s a shame and a crime and I’m not part of it. To me, art is also a very moral thing and you can’t really be an artist without being committed to stopping the insanity that goes on in the world. That’s kind of it. So they gave me this huge bag of money and I moved to the greatest place in L.A., Mar Vista, where I have my own freeway offramp, which is very important to live in this town. I have two beautiful kids that drive me nuts, and a beautiful wife, and I live my beautiful little fairytale existence.

Perfect.

As far as my life with surfing, I bought into the Ranch in 1978 and surfed the Ranch until about five years ago. It’s funny living in Topanga, surfing in Topanga and being a lifeguard in Topanga, I learned how important it was to protect your local surf spot. I’m not into taking it to a point of violence, but the Ranch had a covenant when you bought in that you couldn’t take photos of the surf there. They didn’t want any pictures of what was going on surf-wise at the Ranch. At Topanga, Shane and Craig. were holding it down. In the late ‘70s, I would go surf Mexico a lot at a place called Scorpion Bay. The whole thing was that you couldn’t tell anybody and you couldn’t take anybody. If you were allowed to be part of these special places, it was world class in its own way. It was like Baja, California. If you burned it, you burned it for everybody and yourself. You paid the price because not only did you fuck everyone else’s trip, you fucked your own trip. I was very privileged to learn how special these places are and how you have to protect them. The bragging and your own ego comes back to bite you. Not only is it bad taste, but it comes back to bite you. By burning a place, you burn your own chance of enjoying it. That was my induction to being educated about what was valuable in surfing. I think that’s true of everything. The more you keep your own self private, the more you enjoy the privacy and the world. It’s a celebrity-driven culture, but there’s a big price to pay for that kind of notoriety. Topanga really showed me that sometimes it’s better to just act and not be recognized for your actions. I try to apply that to the art world, but it’s hard to find that in our world because you’re showing your art and if they don’t know who you are, they’re not going to give you a chance to show it. It’s very much driven by being known. If you’re not known, your chances of showing other people your art is pretty problematic. To paint a painting and never show it to anybody is a hard one because there is a certain aspect of art that does demand an audience. How big does the audience have to be? I don’t know. You could show it to one person and I think that’s good. It’s not really what we think about art. Maybe not even showing it to one person is better. When I’m doing a performance on stage, if you’re there, you see it, but then I erase it. If you weren’t there, well, then you didn’t see it. It’s like a musician. When a musician performs on stage, if you weren’t there, you didn’t get to see it. That’s it. It’s gone.

There’s an old Chinese proverb that says, “If you think of the idea, that is enough.”

I think so. Ideas give you pleasure. When we end up at the end of our life, what is the accumulation of our experiences and knowledge worth? Why do we have to die? Why do we accumulate all of this experience? All your fame and everything really adds up to nothing. It can’t be genetically passed on. I think that the joy of learning and having that thought is really very special. For people that enjoy doing and thinking, I think that’s the real reward, just having the idea. I do enjoy painting and surfing and all these other things that we all do and that is enough. Getting the experience is really the only thing we can be sure of. Doing this is really about the journey and the concept. Those are the rewards. I think the thing is to realize that the value in something is doing it and not sitting back on our haunches and waiting for recognition. It might come despite ourselves. I think the people that got the recognition they deserved didn’t seek the recognition. I think it’s a lot of being at the right place at the right time that’s a big part of being a celebrity. Nothing is really lost in the art world. If one person sees a painting and enjoys it, it’s a universal event. If one person sees it, it’s like the universe seeing it. It’s like a fractal in math. It’s Mandelbrot. It’s a beautiful mathematical realization that everything is based on seashells and water swirls and it’s a powerful force that’s made up of little tiny mathematical equations. It’s not a big equation. It’s made up of all these tiny equations put together. If you consider flowers and seashells beautiful, which I think we all do, they’re all made up of tiny fractals, these tiny elements that are linked together. I think if we all just stopped worrying about what other people are doing and just did our own thing, and enjoyed what we do and didn’t worry about being recognized for anything, I think it would change the world and the direction it’s going.

FOR THE REST OF THE STORY, ORDER ISSUE #73 AT THE JUICE SHOP…

SHARE THIS POST:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

One Response

To get this much information out of Norton might be the one of the great feats of all time. And he has so much more info in there. One of a kind.