SKATEISTAN

Interview with OLIVER PERCOVICH. Interview by JIM MURPHY. Photos by CHAD FOREMAN, HAMDULLAH HAMDARD, and JAKE SIMKIN, Courtesy of SKATEISTAN.

A skater goes to Afghanistan and shares his love for skateboarding with the local kids, many of whom have never seen a skateboard before. As he sees the youth expressing themselves through the freedom of skateboarding, with limited resources, he decides he needs to build them an indoor skatepark and school, and Skateistan is born! Once I heard Oliver Percovich was from Australia, it all made complete sense to me! Australians are the real deal and, when it comes to skateboarding, it makes sense that a skater like Oliver would find a way to make this impossible vision happen in a war zone! This is an incredible story and vision that is expanding beyond Kabul and helping at-risk youth around the world! Oliver Percovich – international skateboarding advocate speaks!

Hey, Oliver, what’s up? It’s Murf.

Hey, Murf, it’s great to hear from you.

Okay, first things first. Name, rank and serial number.

[Laughs] Well, I haven’t been tattooed with a serial number yet but, until then, my name is Oliver Percovich and I’m the Founder and Executive Director of Skateistan.

When were you born?

I was born in 1974 in Melbourne, Australia.

What was it like growing up in Australia and when did you start skateboarding?

I first skateboarded when my cousin lent me his board when I was five years old. He was a skateboarder in the ‘70s and he had a 1973 Lightning Bolt with SGI trucks and Slick Stoker wheels. I borrowed that and I was having so much fun on it that he gave it to me. He was probably 13 at the time and it was just before my sixth birthday. After a month or two, we moved to Papua New Guinea. I brought that skateboard with me and one of the most amazing things was that the hotel that we were staying in had an empty pool! I’d seen photos in Skateboarder magazine of people riding in pools and I thought, “I’m going to try this.” Basically, I rode straight into the wall and fell off my board. I couldn’t really work out how to get up the wall.

That’s so sick. Did the management yell at you or was it was just wide open?

Nobody tried to stop me but, after awhile, I gave up because I was just slamming into the wall. It was way harder than I thought. All I worked out how to do was tic tac and roll down. The board I had was a skinny fiberglass board and it didn’t have any grip on it, so I had to work out how to actually stay on it as well. We didn’t have loads of places in Papua New Guinea that were smooth enough for skateboarding, but I brought the skateboard with me to both schools that I went to and I started skateboard crazes in both. Within a few days, both schools banned skateboarding.

That was when the skatepark craze was dying and everything went underground. Before you left Australia, had they started building concrete parks there?

There was a wave of skateparks built in the late ‘70s, like Melton and a couple of others, but I never rode them because I was too young. We came back to Australia at the end of 1984 and I remember Back To The Future came out and that was the first movie I had ever seen that made me really excited. It reinvigorated the whole idea of skateboarding. In 1985, the Variflex team did a demo at a local shopping center. They had a little competition at the shopping center, and I entered into it. I did a sess slide and tic tac-ed around some cones and I did a little flip thing where I flipped the board from standing to standing on it. I won a deck and that was the only skateboarding competition I’ve ever won. My mom helped me get some trucks and wheels for it, and that was my first wide board.

Nice. I remember when we did an Australian tour in ‘88 and ‘89 with Alva, there were still old concrete parks there. Did Australia doze their parks after the ‘70s?

They dozed Melton, but other ones survived. The first one that I skated in Melbourne was Bulleen bowl, which was also built in the ‘70s. It was a downhill snake run and it was pretty rough concrete. That was our skatepark in 1985. There was this wave of skateparks that got built in the late ‘70s and that’s what we had. Prahran was there and then the Prahran Ramp got built in ‘87. In ‘87, there was quite a lot of stuff and there was the Torquay Ramp Riot. That’s when Cab came out and did the highest air at the time. I think he did 13 foot. We had loads of really rad demos in ‘87, ‘88 and ‘89. That was such a peak for skateboarding and that was a really exciting time for me.

Were you riding vert too?

No, not really, unfortunately. My really good friend, Tim Bartold, was skating vert, and quite a few other friends, but I was skating eight-foot ramps. I built a ramp myself, me and my brother, Chris. I got my brother into skateboarding in 1985. He’s four years younger than me. In ‘86, I built a ramp as a 12-year-old, that was 8-foot trannys cut off at 6 foot, so that’s what we were skating. I also skated other ramps that were up to about 8-foot.

Were you into reading skate magazines and did you have pros that you idolized?

My first skate magazine was a TransWorld with Tod Swank on the cover pushing. I had some Thrasher magazines, but it was expensive for us. We had to pay like $16 for a skate mag from the U.S. As a 12-year-old, that was big bucks. Any money that I had went towards skateboards. I remember the whole line of boards that I had. It was the Lightning Bolt, and then a Variflex and then I had a second-hand Local Motion, made by Santa Cruz. I had a Jeff Phillips, two different Caballeros, a Ron Allen and a Tommy Guerrero board. That was up until ‘88.

Then skateboarding started to go more to street skating. What was going on with you around ‘89 and ‘90?

I was just concentrating on school. In ‘91, I had a friend in school and we’d skate every day. I was mostly street skating. In ‘91 and ‘92, we were just skateboarding, studying and listening to Metallica. I moved out of home when I was 16, because my dad died when I was 14, and then it was kind of tricky with my mom. She wouldn’t really let me do anything and I was a very independent person. I wanted to look after her and do things, but she wouldn’t let me do stuff. We lived quite far out of the city, so I was already hitchhiking a lot just to get about. In ‘91, I moved to the city into a student hostel and I was just skateboarding and studying. In ‘93, I went to live with my grandma in Germany. There was a real resurgence in the skate scene in Germany in ‘93 and it was all about street skating. I was really into skateboarding and I was learning a lot of tricks. It was a year of not going to school and just hanging out.

So you spent a year in Germany before going back to Australia to go to college?

Yes. My grandmother bought a car for 400 Euros and I drove 50,000 kilometers in six months, and went all over Europe, going on skateboarding trips and hanging out with friends. I went to Prague a lot and I was going to Holland and I ended up living in Slovenia. I got a girlfriend that was five years older than me, and I was pretty excited about that. That was a cool time. There was a lot of people joining up together – skateboarders, punk people and straight edge people – and creating an underground nightclub scene. Italians would come over the border and go to it and it was a real DIY scene. The Italians were just coming out of communism, so they were pretty stoked on it. 1993 was a cool year for me. I was 18 years old and I just traveled around Europe and then I went back to Australia and went to university.

What were you studying?

I studied environmental science. At the start, it was biology and chemistry, and I ended up taking on the chemistry. I failed some first year subjects because I started snowboarding a lot and missed a lot of classes. Renton Millar went to my university, so I got to know him. One of the only times I skated vert was with Renton. There was a 13’ ramp in Cranbourne, one of the biggest ramps in Melbourne, and Renton convinced me to drop in on it.

Did you pull it?

I slammed pretty hard the first try and then I did it the second time and I did a rock n’ roll first shot.

Were you stoked that you dropped in on a vert ramp?

I actually hit my head when I dropped in the first time, so I was kind of dazed. I knew I had to do it again right then or I wasn’t going to do it. I made the drop in, but that was it.

Did Renton give you a high five or what?

Yeah. He was pretty hyped on that. I actually took Renton snowboarding for the first time. I taught him snowboarding and he taught me how to drop in on a vert ramp. Then I got into street skating quite hard. At that time, I could ollie over a tractor tire, so I was pretty decent street skater.

That’s cool. What was your goal of going to university? What was your vision for that education?

I was really interested in environmental causes and I saw myself getting a PHD in chemistry so I could maybe go work for Greenpeace or something like that. I was into protesting about environmental injustice, so that was the emphasis behind studying chemistry.

What did you do when you graduated? Did you get a degree in chemistry?

Up to the end of the environmental management degree was the third year, and then you can do an honors year and I chose to do the honors year in chemistry, so that was an applied chemistry degree in the end. The thing that I worked on was removing heavy metals from waste water. We put waste water onto crops and then heavy metals stay in the root zones and then we eat those crops and then the heavy metals accumulate in our body, so I was trying to work out a way of removing the heavy metals from waste water before it gets put onto crops, so it’s not accumulating in humans and causing damage. That was the idea. After that, I worked at a friends dad’s butcher shop. I was in the back mincing meat and making sausages and I was a vegetarian at the time. [Laughs] I just wanted to prove to myself that I could do anything. After that, I got a job at a university in the social science field. I was working with a professor that was an expert on flooding. It was all emergency management and how to deal with natural disasters, like floods and fires. I started working as a researcher and I couldn’t believe that I could sit there and earn twice as much money as I was mincing meat and carrying around hams.

Were you wanting to do something more hands on and out of doors?

Well, the first year, I was okay with it and we won some national research awards. The professor that I was working for really left me alone and I’m a really independent person, so he was just letting me do my thing. He was a super cool boss and it was a super cool job. At the same time, I got myself into a pretty bad place, just working in an office. Growing up, we never had a television so I never watched TV, and I was into reading books and that sort of thing. After I got the office job, I was just going home and watching television and starting to drink more and getting depressed. At the same time, I created a business selling bread and making food and selling it at a market.

You were working a 9 to 5 job and then you’d go home and make bread?

Yeah. I had this market store on Saturday and I would sell bread and quiches and different things I made up. I did it together with my girlfriend at the time. She was Swiss, and she had a lot of really cool recipes, so we made baked goods and sold them at the market. It was a pretty successful business. At one point, I was earning twice as much in one day at the market as I was working two weeks as a scientist, so I left the job at university and started to just do the market. The rest of the time I was just skateboarding, surfing and traveling. I got myself into a pretty cool place that, in a way, wasn’t so cool because I didn’t have a real purpose.

It’s around 2000 by this point?

It was 2001, and I knew that I had more to offer than running a bread store once a week and just hanging out. I was actually partying quite a lot. I never got into drugs, but I was starting to drink a lot. It got to the point where my brother, who is my best friend, didn’t want to talk to me or hang out. I really got in a bad place. That was a bit of a wake up call. At some point, I tried to turn things around and I moved to Alice Springs in central Australia to work in health services with indigenous people that had mental disabilities and had been charged with serious cases. I didn’t know before I started the job that the two guys that I was working with had both been charged with murder. I guess my job was like a glorified jailer, in a way.

No way.

They had a house that was given to them and we did these 12-hour shifts. During the day, we would take them to hang out with their family or drive them around and then take them back to the house. It was an alternative to them being in the system and being institutionalized.

So you go from making bread and skating and surfing to working in a halfway house. Was that a transition you liked?

That was kind of exciting for me because I had this job that other people looked at as an impossible job and they had a really high turn-over in staff. They put me with the hardest cases that other people didn’t want to touch. I ended up getting heaps of hours and I was ready for it. It was pretty cool. I had a skatepark out there in Alice Springs and I would go to the skatepark and skate. I had a dirt bike that was lent to me, so I would ride out early in the morning into the desert by myself. I had this super interesting job and we would go out on these desert trips to visit the original families of the guys. We would do these one-week camping trips and I was getting paid 24 hours a day to be the minder. It was really interesting and it piqued my interest for working with indigenous communities and what the challenges are for them in Australia. I learned a lot about them and how big these communities were. In the camps that I went to, the people were sniffing petrol and the kids were sniffing solvents from spray cans. They were huffing that stuff. The adults were bringing back five liter castes of white wine, 12 at a time, which was 60 liters of wine and they’d finish it in an hour and a half. They were breaking windows on cars and houses and just going crazy. It was interesting to realize that this is Australia as well.

These were the Aboriginals?

Exactly. This is a huge issue and it was something that I was very passionate about and interested in from a pretty young age. In 1988, we had our Bicentennial and everybody in school in Australia got this medallion for the 200 years of the colonization of Australia. I got my medallion and hacksawed it into pieces and wrote on everyone’s cars that the Bicentennial sucks. I made a lot of girls in my class cry at that time because I wrecked my memento.

So you were in tune with what the government had done to the Aboriginal people of Australia and that affected you?

Yeah. It was something I had been pissed off about for quite some time. Being out in Alice Springs and seeing the magnitude of the problems, made me think that I wanted to work on how I could do something positive there, but I really felt at a loss because I saw how deep the problems were. I really saw it as a lack of trust between indigenous Australia and white Australia. There was a very good reason that the indigenous population didn’t trust the white population because they had screwed them over for so long. They had taken kids out of their families and done all sorts of crazy stuff over generations. The solution that the Australian government came up with was just to throw lots of money at the problem. When you’ve got no trust, and then you’ve got money, you’re not going to have a solution. You need both social capital and financial capital to solve a problem. You can’t just throw financial capital at a problem where trust doesn’t exist. That was my conclusion. From there, my girlfriend at the time got a scholarship in Hungary, so I moved to Hungary and lived in Budapest for a couple of months while she was there, and then we moved to Morocco. While we were in Morocco, she applied for a job in Afghanistan.

What was the job in Afghanistan?

The job was with the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. They were a think tank and research organization in Afghanistan. Because I had a background in research working in a university, I tried to get a research job in Afghanistan too.

The military was active in Afghanistan then, so what was the social climate there? In Morocco, were you looking at Afghanistan as an active war zone?

Yeah. This was 2006. In 2001, the U.S. and a couple of other countries basically invaded Afghanistan, and together with the mujahideen, they drove out the Taliban and propped up the Afghan government. The Taliban and the Afghan government and the international forces were still fighting in a lot of places in the country, but Kabul was relatively safe. My girlfriend went there in September of 2006. At the time, I was staying at a friend’s house in Germany and one of those guys was a pro skater. Just before I left to go to Afghanistan, he gave me a couple of boards to take with me.

Cool. What was your friend’s name that was a pro skater?

It was Benni Dittrich. He rode for Santa Cruz for a little while. My girlfriend, Sharna, was already in Afghanistan, but I kept working in Germany and I was basically just surviving. In February of 2007, I went to Afghanistan to join Sharna there.

Describe what Afghanistan was like when you got there.

Well, I got this super cheap flight from Germany to Dubai for $200. Then I figured I would be able to get a flight from Dubai to Afghanistan because it was pretty close, but I ended up having to pay another $200 just to get that one-way ticket. I had done loads of reading for the three months before that to find out everything about Afghanistan, so I had a good background in terms of what I had read. On the plane flying in, I was pretty nervous. I kept saying to myself, “If worse comes to worse, maybe I’ll die or something bad will happen to me, but I’m ready for this.” When I arrived at the airport, everything was way gnarlier than what I imagined, in terms of how bleak and difficult it was there and what the city looked like.

Well, the first thing that I would think would be hard would be the language barrier. How did you figure that out?

Yeah. There are two main languages there, Dari and Pashto, and I didn’t know either. I made my way through the airport, and my first impressions were seeing a dude with a wheelbarrow and another guy on a donkey. The roads were a mess too. They were coming out of winter and it gets really cold there, way below freezing, and the roads aren’t sealed, so they have these muddy roads and the taxi is going through these massive potholes that are just filled up with water. I was scared the taxi was going to come off the road. I was really expecting a city that was more modern, but it was just a messed up place.

What was the vibe being a white person in Afghanistan? What was the general vibe towards people coming in from outside of Afghanistan?

Well, right at the start, I was pretty nervous. I was just trying to feel my way and find out what the people were like. By this time, I had traveled to 42 different countries and I was ready to work out what was going on. Within the first week, I was walking around to different places and everybody was so friendly. When I got over my initial fear, which only took a day or two, I started to feel more comfortable and I started going to the market by myself and catching taxis around and working out how to say a few things in Dari. I started to explore the city and I bought myself some local clothes. I was just driving around with a camera around my neck and then the most fucked up thing happened to me. We were going past this U.S. military base and this soldier came out on the street and he saw me sitting in the taxi with the camera around my neck and he freaked out. He came up to me and said, “Give me that camera!” I said, “No!” I wouldn’t open the window and he was rapping on it with his gun. I was like, “Oh god, this is really getting bad.” He yanked me out of the taxi and pushed me down to the ground and held a gun to my head and pulled me onto the base. They took my phone and my notebook that I had in my bag and they put me in a room. I was like, “What the hell is going on?”

Were they interrogating you or what?

Yeah. They were asking me questions and then they went out and left me there for four hours. I was absolutely shitting myself at this stage. I thought I was going to be sent to Guantanamo or something. I had a diary in my notebook and I was thinking, “Have I got any sort of anti-American things written in my diary?” I was getting really scared. I was really against the military and I didn’t know what I’d actually written in there.

What were they asking you?

They were like, “What are you doing here? Why are you filming? What is going on?” They thought I was trying to plan some attack on the base because I had local clothes on and I was a foreigner. I was like, “I’m an Australian and I’m basically a tourist.” They just didn’t believe it. In the end, they let me go, but they kept my camera. They told me to come back the next day and pick it up again. The next day I turned up in a baseball cap, looking as American as I possibly could, hoping I could get my camera back and not get locked up again. I was pretty scared going back there. That was the start of it. The local people were super friendly wherever I went and they were asking me in for a cup of tea. Even if we couldn’t communicate, they were very friendly. I was just this white guy walking around the streets and exploring the city. I’m a calculated risk-taker, so I felt comfortable.

You would think the locals would be the ones to grab you and throw you in a room and start questioning you, because you’re a foreigner wearing local garb, but it was the opposite.

Exactly. It happened again and again. We were going around the streets and some military vehicle would come up behind us and you’d get the laser beams from their laser sites coming in on your dashboard. You’d be like, “Oh my god!” You’d get off the road really quick then. I was more scared of the international military than anybody else. They were the main threat. I was living in this guesthouse where there were other people that were working for the U.N. and places like where my girlfriend worked. I was applying for jobs in Kabul and I didn’t really find anything and then somebody asked me if I wanted to do a job on the military base, running a bar for a night. I decided to give that a go, so I went onto the base and it was really interesting to see what was going there with these 16 different countries and 1,500 soldiers.

What was the attitude of the people there and the soldiers?

Well, I just had this one-night job and they were so impressed with what I was doing that they asked if I wanted to come back and take over this coffee bar. During the day, they were serving coffee and tea and, at nighttime, they served drinks, so I took on that job and I built it up pretty fast. They were doing $200 a day when I took it on and I grew it to $2,000 a day, but then I got fired from that job.

Why did you get fired?

I had some Filipino staff working for me and one night we were running this event and this Polish general got pretty drunk and he was saying racist stuff towards my staff and I got him kicked out. His payback was to get me fired because I was sort of smuggling girls onto the base to work behind the bar. These were women that normally worked at the U.N. They were earning like $10,000 a month in these really high-powered jobs, so they were really hyped on the job, and they saw it as a thrill to go on the base. On this base, you have 1,500 dudes and 80 women, so it’s just all men. I worked out that if you put pretty girls behind the bar, then you sell loads of drinks. [Laughs] I was sort of breaking the rules of the base by smuggling these women in to work behind the bar because you were supposed to go through this whole process of getting them passes. I was breaking the rules a bit, because I was just escorting them on and off, so there was that. The Polish general got me back by blocking that because his guards were on the gate. The Afghans didn’t like me either because I was breaking all of their rackets, because I knew the price of everything in the markets. I knew how much milk and bread cost and there were certain Afghan people on the base that were ripping off the company that I was working for by charging them double the amount. I cut off all of their business and went out onto the street myself and sourced all of the stuff, so they were pissed with me because I had broken their little racket. I just made too many enemies there, so they fired me. Around that time, the weather started to get better. We were coming out of winter in 2007 and I started to skateboard with some Afghan friends and a couple of other ex-pats that were there.

Where were you skating?

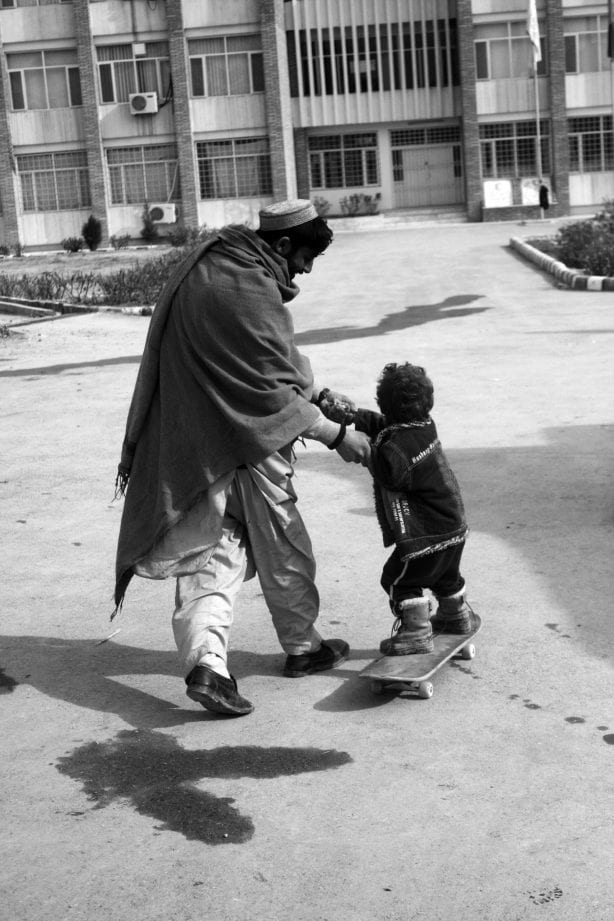

We were skating Amani High School, which was just flat ground. There was a basketball ring on the ground, so I was skating that pole and we had these goal posts that we were able to flip down and skate. Then there were some kids getting interested in skating and we took a couple of photos of them. They were riding my skateboards that I brought to Afghanistan. I had three skateboards – one of mine and two from that pro skater in Germany. One of my Australian friends there was a photographer and he was taking those photos. He got those photos in Vice in 2007, and there was interest around skateboarding. What really tripped me out was that there were these really poor kids wanting to skate and there were girls as well and that was really amazing to me.

Did you know the differences of how boys and girls are treated in Afghan society?

That was apparent straight away and, from all the reading I had done, I knew. There were no women driving cars. There were no girls riding bicycles or playing sports. When the girls were trying skateboarding, they saw me as potentially someone that was going to give them money because I was a white guy on the street. I was like, “I’m not going to give you any money, but here, ride my skateboard. Try this out.” So they started to skate and they were getting into it and I thought, “This is amazing. Girls are doing a sport and no one is really saying anything about it.”

How stoked were they when they got to ride your boards?

They were crazy about it. They wanted to take the skateboard. I was like, “No. You can’t take the skateboard. It’s the only one I’ve got, but come back and we’ll skateboard again.” The Afghan friends that I had made, some 20-year-old guys, had really gotten into skateboarding too, and I was teaching them little tricks, doing bonelesses and whatever we could do with whatever we had. Then I had the idea that maybe we could build a mini ramp somewhere. There was no big idea besides the fact that it was really amazing that the Afghan kids were skateboarding. Then I thought, “Why don’t we bring some more skateboards here? It could be a really cool thing.” Then I got offered a research job in Kabul. Just before taking that job, I went to India for a break. I also broke up with Sharna, my girlfriend, who was the reason that I had gone to Afghanistan in the first place. So I was in India and I rented this really cool old school motorbike and I rode from Delhi to Calcutta in a couple of days. That was crazy. It was 700 miles and I did it in three days. You can only go about 20 miles an hour most of the time, because you’re going through cities. It was a really heavy motorcycle as well, and it’s a lot of stop and start going through towns and just riding 12 hours a day, but I was on a mission to make it to Calcutta.

What was Calcutta all about?

I just picked a point on the map and decided to go there. It was a little bit of soul searching I guess.

Did you have your skateboard with you?

No. I left all my skateboards in Afghanistan with the older Afghan kids that I was friends with that were into skateboarding. After I got to Calcutta, I rode north and a cow walked out onto the road in front of me and I swerved to miss the cow and the bike went over and I slid a really long way off the bike and smashed my shoulder to pieces. It was super gnarly. I was on the ground knocked out and a bunch of people ran over and poured water over me and brought me to a hospital. The doctor in the hospital told me it wasn’t broken, but I was in such pain that I got myself out of the hospital because there was blood on the walls and I didn’t really trust the diagnosis. I checked myself into a hotel and I was in super pain, so I took heaps of painkillers and the next morning, I self-medicated with some whiskey as well. Then I got my motorcycle out of the police compound because it was a rental bike, and it was pretty thrashed up. I rented a little truck and put the motorcycle onto the truck and I went with my broken shoulder on this truck back to Delhi. I was just trying to get back there, so I could get to a better hospital. It was like a 13-hour trip and I was in such pain by that stage. I checked myself into a private hospital and they did a scan of my shoulder and said, “It’s totally smashed up.” I was trying to get a flight back to Australia, and that was not working, so I unplugged all my drips and walked out of the hospital and went to a travel agent and booked the flight myself. I got back to Australia and I couldn’t get ahold of anyone in my family, so I checked myself into a hospital. Luckily, I got a good surgeon, and he fixed me up. While my shoulder healed, I started writing proposals for the idea of Skateistan. From there, I was trying to get back to Afghanistan.

Wow. Was it that trip in India where the idea for Skateistan came to you?

No. It was just me thinking it would be really cool to do something with skateboarding in Afghanistan. The other two people that I was doing it with, my ex-girlfriend, Sharna, and this guy, Travis, an Australian guy, were still in Afghanistan and they came up with the name Skateistan and I was like, “Hey, what is going on guys? Let me know about what you’re doing.” It was me that introduced them to skateboarding and brought the skateboards over and was driving the whole thing. I guess Travis was a photographer and he was trying to make something of it. I think Sharna saw it as a way of staying involved and doing something with me. I was like, “Hey, what are these ideas that you’ve got?” So they showed me what they had, which were a couple of ideas on a page and I fleshed that out into a larger proposal. From that point, because I knew some people in Australia to do with skateboarding, I gave it to the Globe people. They were like, “It’s a really interesting idea, but I don’t know if we can help you with anything like that.” Then an old skater friend from the early ‘90s, Barnaby Lawrenson, was working at Black Box Distribution and I got a hold of him and asked him if he could help us out with some skateboards and shoes and he was into it. He was in the U.S. at the time and he asked Jamie Thomas and Jamie said yes, so he agreed to give us this skateboarding equipment. I was like, “Rad! Wow! We can really do something now!” They gave me all this gear, so I was ready to get back to Afghanistan and get skateboarding with it all.

Were you telling them you were starting a non-profit or were you just asking them to flow you stuff?

I was telling them this idea and asking them to flow us stuff. It wasn’t developed into a non-profit yet. The proposals to the skateboarding companies were just, “Hey, can you give us boards?” Then I had a friend that was running a bar in Melbourne, so we asked if we could do a fundraiser there. We did this fundraiser and, as soon as my shoulder was a little bit better, I started to work on a building site helping to build this mud brick house. It was a crazy thing to do for someone recovering from shoulder surgery, but I really wanted to get some money together and get back to Afghanistan. So I saved $1,500 working on this building site and my mum gave me $2,000. My mum doesn’t have that much money, but she knew that I really wanted to go back, so she lent me some money. I had money to buy a ticket back to Afghanistan, but I could only carry a couple of skateboards back with me, so the skateboards from Black Box were stuck in Melbourne. I was trying to work out how to get the boards over and a friend told me about the Mekroyan Fountain in Afghanistan, which was this place that looked pretty good to skateboard in. He told me I should go there and skate it so, when I got back to Afghanistan, I went there and it was rad. It was an old fish pond in front of a hat factory that was built a long time ago and it had skateable transitions with coping block on the top, so we started these skate sessions there. For the first few weeks, it was just boys, but soon enough the girls were coming closer, and then they tried it and they loved it, so I’d go back to the Fountain every day. At the same time, I was being warned by foreigners not to go there because it was dangerous to skateboard with the kids and they told me I shouldn’t be doing anything with girls.

When the locals were walking by, was there anyone saying anything to you?

Yeah. They were like, “What is going on?” I always had some Afghan volunteers, guys in their 20s, that were translating and helping with the sessions, so I tried to stay in the background as much as possible. I brought the skateboards and put the skateboards down and I would make sure that the boys and girls were skateboarding separately. I did three times as much time for the girls to skate as for the boys because I was so much more stoked for the girls to be doing it because I knew that they couldn’t do other sports. For me, it was like being transported back into time when no one had seen a skateboard before. I didn’t want to show them how to skate because I wanted to watch how they would try to learn to skate.

How did they adapt to it?

Well, the first thing they would do was put their foot on the nose and try to pivot off the nose. They were trying to tic tac backwards. They were standing on the board looking backwards and they would try to propel themselves in the way that they were looking off the nose, but it doesn’t work. You just go backwards and forwards and stay in the same spot if you do that.

Is that when you would step in and help?

Yeah. I would skateboard a little bit and some of the other older Afghan boys were skating as well, so they started to get it. On the whole, I wanted them to just experiment with it and interact with the skateboard. I didn’t want to have too much interaction with the kids either in terms of if that got seen badly by the community. I was just letting the kids play on these things, so they developed their own thing. They never really learned how to push much because they had these transitions where they could roll up and down. The Fountain is like this dish, so they were learning how to stand on the board and then they’d get each other to push them around in a circle. They knew how to turn the board, so they could skate pretty well until they ran out of speed or the person didn’t want to push them around anymore. They learned how to tic tac and then they learned to get speed from that and then they started carving up the dish and carving back down again. They were riding it like a wave and going around in circles. They learned how to do that frontside and backside and then they were dropping in on it.

Seeing that transformation, did you see the happiness in their faces about what they were doing?

Oh yeah. They were ecstatic about it. They were crazy for the skateboards. By that time, I had eight skateboards because I had brought a couple with me on the plane and some other people had brought skateboards from Melbourne from Black Box. I had this stack of eight boards on the back of my motorcycle and the kids would just swarm the motorcycle as soon as I turned up the road. They started running after me and grabbing the boards off the back. They were crazy for it. They would skateboard for hours until it would get dark. The next day I would come back and we’d do it all again. The really cool thing was getting to know the kids better. For me, I was so stoked seeing that there were kids that lived in the flats around there that were more middle class Afghan, and the really poor kids that lived on the streets, were all skateboarding together. Normally, they wouldn’t mix. I was like, “This is amazing.” The different ethnicities in Afghanistan really hate each other, but on the skateboard, they were skateboarding together. I was like, “This is so cool!” There was potential there. Then I started to get to know the kids better and they told me how they wanted to go to school, but a lot of the time they couldn’t. The poorer kids weren’t going to school, so I tried to work on a way to get some of the kids back into school. I got one of the girls back into school through our Afghan friends. They talked to the parents and told them, “If she is a skateboard instructor for two hours every afternoon, we can give her $1 or $2, so can she then be allowed to go back to school?” The parents had pulled her out of school so she could beg on the streets. She could only make $1 or $2 begging every day, so I was like, “Hey, I can employ her as a skateboard instructor.” There needed to be girls teaching the other girls, and it worked out perfectly. She was stoked on her job and she got back into school and she was really happy and she got heaps of girls involved, and it started to grow. First, there were 10 skaters and then there 20 and then there were 40 and then there were 80 kids at the Fountain every day. I would have these eight skateboards and each kid would have to put down their name and they could skate for 10 minutes and then it was the next kid’s turn. It was easy to give double time to the girls, consequently, the girls got better than the boys at skateboarding.

So you have girls teaching other girls and you’ve got more girls skating. At what point did you start thinking that you needed a facility with an indoor spot?

That was really from doing little competitions where I saw the girls were beating the boys, after the age of 12, but I couldn’t skate with the girls over the age of 12 outdoors, because girls over the age of 12 can’t mix with males at all. Girls and boys can’t mix with each other after the age of 12 at all, in the street, at school or anywhere. It’s just how the society is segregated. They want to basically protect the girls from the boys. People will say that it’s a Muslim thing, but I think it’s more of a tribal thing in that area. That’s just the way it is. Boys and girls are separated from puberty onwards. Girls are also married off at that age as well. I found out that half of the population in Afghanistan was under the age of 15, and I really wanted to offer skateboarding to girls between the ages of 12 and 17 as well. What we needed to do then was to have an indoor facility. We had a couple of girls that were 11 or 12, and some of them were dropping off. I was like, “Why can’t she stay involved?” They were like, “The parents are stopping her being involved.”

So these girls would just fall off the radar and you would never see them again?

Exactly. They would just disappear. If we built an indoor facility, I thought maybe we could combine skateboarding with educational opportunities because I saw school as just so bad there. School in Afghanistan only goes for two hours a day and the teachers hardly ever turn up, so the kids are just doing rogue learning. They’re learning by memorization and I thought that was not going to solve problems in Afghanistan. You’re never going to have foreigners coming here with their Harvard degrees and solving the problems in Afghanistan. Only the Afghans are going to solve Afghan problems. If they go to school and just do rogue learning, they are not going to learn to solve their own problems. They need real problem solving skills and they need a quality education. They need a creative place in their education, so I developed the idea to build a school that would have a skatepark in it and we would have separate boys days and girls days. I started to shop this idea around and I was knocking on doors to find out who the donors were in Afghanistan. I was really lucky because I got an Afghan building company to agree to build the facility, and I got the Afghan Olympic Committee to donate land by bringing the president out to the sessions at the Fountain. He was amazed. He was like, “Wow! What’s this? I’ve never seen skateboarding before. This is amazing! I can give you land.” I then convinced the Canadian government to give me $5,000. I was just scraping by and I was really questioning my sanity. I was living on nothing and trying to do something in a war zone so far away from my family. Everyone was telling me I was totally crazy and it was way too dangerous to be doing this. To me, it just made sense because the kids were so stoked on it, and I saw that as a solution for Afghanistan. The kids need higher quality education and connections around the world. The trust needed to be built and this went back to my experience working with the Aboriginals in Australia and my background in social science. After natural disasters, one of the things that helps a community bounce back is how much social capital there is and how much trust there is and how many links they have in that community. The more links they have in a community, the quicker they bounce back after a disaster.

In that very beginning stage, when you’re asking around, did you find that the Afghan parents were into what you wanted to do?

They thought it was really weird. Anyone that really saw what was going on didn’t understand it. In a way, every parent in the world wants to see their child happy and these kids would come back beaming. We would take photos of them and print the photos out and give them the photos and they would bring them home to their parents. They introduced their parents to what skateboarding was and they were so happy skateboarding that the parents were like, “Well, my kid is happy. I guess this is alright.” They didn’t know what to think of it. They just wanted to see their kids happy. The donors really got into it too. I explained that half of the population is under 15, so you’ve got to engage with them right now. If you don’t engage with them now, you’re in a lot of trouble. Into the future, they need a high quality, creative-based education. They can’t just rely on rogue learning. In these skateboarding sessions, we’ve got rich and poor kids mixing together and all different ethnicities mixing together. There has been $5,000,000,000 pumped into Afghanistan and you don’t have any results, because you don’t have any social capital. Nobody trusts each other. In these skateboarding sessions, this is a small way, person by person, that trust is being built. Skateboarding is such a big hook that people are coming together and they don’t care what background the other people come from. They just want to skate and they’re having a good time together. I never went to Afghanistan with the idea of starting a NGO (non-governmental organization). I never went to Afghanistan with this big vision of doing something. It was just step-by-step that these things made sense. It was this feeling that kids were so excited about skateboarding, so I couldn’t just pack up my boards and go back to Australia and leave all of these kids behind that were so excited about what was going on. I convinced the donors and we built the biggest indoor sports and education facility for kids in the country. People were buying into the vision and it only took four or five months to build the whole thing.

When you were talking to donors, were they like, “You’re going to have to start some sort of non-profit.” Were you like, “What is that?”

Exactly. I knew I needed to learn step-by-step how to make a non-profit. I found somebody else that had a non-profit and I looked at their bylaws and copied those and inserted Skateistan. It was funny because I had always had a real skepticism about lawyers and accountants. All of a sudden, lawyers and accountants were some of my best friends.

What countries stepped up to finance it?

Canada put in $15,000 and the next donor was the Norwegian Embassy and they put in $36,000. Then the Danes got involved and they put in $100,000. As soon as one saw one get involved, they all wanted to get involved. When you’re just starting something out, no one wants to back the crazy idea, but as soon as you crack the ice and get some money involved, I was amazed at all of the people that got behind it. My wildest idea was to build a facility that was 800 square meters, and the Afghan Olympic guy said, “I can give you land for 2,400 square meters. Can you build something that big?” I said, “Well, I don’t know. I guess I can.” We didn’t have any money yet, but the plans just kept on growing and we kept on adding more stuff in there as we could. The funny thing with the donors was that they got competitive with each other and they all wanted to be the biggest donor on the project. I kept on adding donors, but something that was quite lucky that I did right then was when the Norwegian ambassador wanted to get behind the project in a big way and bankroll the whole thing, I said, “I’d rather you not do that. I’d rather you help me get other donors on board as well.” So he organized a dinner and that’s how we got the Germans and the Danes involved as well.

How did you come up with that strategy?

That was actually from my bread dealing days. I always had three bakeries that I would buy bread from to sell at my store. If one supplier would drop off, I would have other suppliers to support the business. I just thought the same thing would work with the donors. That way if one donor dropped off, there would be other donors to rely on. It was a good idea because, as soon as the first Norwegian ambassador left, the next Norwegian ambassador didn’t want to support it anymore. Then the Danes doubled again what they wanted to do, so that strategy actually paid off and worked. I was making sure that I had a couple of legs to stand on to back it up. We opened the facility in October 2009 and Andreas Schutzenberger, who built the World Cup Skateboarding ramps in Munster, came over and built the whole park for us together with the kids that were skating at the Mekroyan Fountain. Then we opened up the skatepark.

What was opening day like?

It was really a struggle and such hard work up to that point, that it was unbelievable. What I was really excited about was watching those Mekroyan kids, that had only known this tiny little concrete fountain with all of its cracks and horrible cement, be able to skate this massive skatepark. We have 7-foot quarter pipes and it’s huge and perfect. I just wanted to see the kids skate it, because they hadn’t seen it before opening day. Everyone was there for the ribbon cutting and then the kids went into the park and I had goosebumps. It was crazy.

How did they adapt?

They were going for it and going way too fast and falling all over the place, because they were so excited. They had learned a couple of lip tricks and they were trying to do them on the coping and they were doing rock to fakes without lifting their front wheels and they were just hanging up all over the place, just going for it. It was crazy. It was so cool.

Sick! What about the first drop ins?

They got it pretty fast. They weren’t really good at getting their front wheels down, so dropping in, they were not landing forward enough, so they were doing lots of manuals down the transition. They worked it out pretty fast that you had to just lean way further forward.

You had to scream, “Lean in!” [Laughs]

Yeah! It was so exciting! We skated really late and there were quite a few pros there. Maysem Faraj, a Syrian skater based in Dubai, came for that. Kenny Reed came back out and Louisa Menke was there, which was cool. It was cool for them too because they had come there earlier, so they knew all the kids and they helped finish the park. That was the start of it and we had way too many kids. We had 400 kids registered and we had a massive waiting list of boys. We held half of the places for girls and half of the places for boys, and we had 200 boys and 170 girls. The 200 boys places were taken, so there was this waiting list. We started to hire our first employees and we had to build up the staff and I had to work out how to manage people. We had some international volunteers and then we worked out that it doesn’t really make sense to have international volunteers because it’s an Afghan project, so we should have Afghan volunteers. We were like, “Why do we have foreigners in the classrooms teaching kids English? They should be learning local subjects and doing it all.” We started to train teachers and young Afghans to be part of the scene and then we had 15 staff.

How did you come up with a curriculum?

We sort of made it up as we went along. I went to a Rudolf Steiner school for a couple of years, so I was interested in a creativity-based curriculum, with math and sciences, so kids can really pursue what their interests are and the teachers try to teach them one-on-one as much as possible. It had similarities with Montessori, but it’s not really the same thing. We developed a curriculum that street kids and other kids could also do. My background was science, so I saw that as a way of developing the type of skills that they needed to have. We did photography projects, drawing and painting. I was trying to find out what all of the kids would be able to do straight away and the main focus was just on fun. When they went to school in Afghanistan, they would get beaten and hit all the time, and they just had to memorize things for two hours a day when the teachers actually turned up. I wanted to create something that was completely different. Over time, we got more experienced people and we developed our curriculum more. At the start, the idea was one hour of skateboarding and one hour of creative arts in the classroom. Then it was trying to develop the Afghan staff and having the foreigners as much in the background as possible.

What were the parents reactions?

Well, our theory was that if we could win the kids over, the kids could win the parents over. At the opening, we invited a really prominent mullah and he told a story to all of the parents and everyone there about how the prophet Muhammad encouraged his wife Aisha to take part in a running race, so we had a prominent cleric that everybody listens to saying it was okay for girls to do sports. You don’t actually see girls doing sports in Afghanistan because it became a cultural rule of what boys can do and what girls can do. It wasn’t really a religious thing. So that was a really good move to try to win over the parents with someone from their local community that they really respected saying what we were doing was okay. The other thing was doing home visits. We would send our staff to the homes of the students and they’d ask the parents how they were doing and sit down and have a cup of tea with them and talk to them about it.

What was the feedback?

Well, we focused on the parents of girls. With the boys, we weren’t so worried if they dropped out because there were other boys that could get involved. We wanted to give the girls the best chance because some of the girls would be allowed to do it for a while and then they wouldn’t be allowed to anymore. There was pushback from the families. Usually, it was an older brother or sister that was jealous that their younger sister or brother was having fun. There is a real social pecking order. If you’re older, you get to push around the younger kids. A lot of times, these are just young kids having fun and then they’d be told that they couldn’t have fun anymore. We tried to develop relationships with the parents and then we tried to get those parents to convince other parents as well. I knew that I was the last person that was going to be able to sell this idea to people. It had to be Afghan staff or volunteers doing that sort of stuff. After that, it was like, “How can we engage the kids and the parents to push what we are doing and talk about what the benefits are?

Were the parents convinced and were you seeing a positive relationship develop?

Yeah. A really big reason it was working was that we had separate days for boys and girls. We had female instructors for the girls and that was something that they accepted. The other really big thing was that I didn’t introduce any Western culture with skateboarding whatsoever. I didn’t show them any videos or magazines or fashion or music. I knew that if there seemed to be any sort of Western influence on the kids, the parents would say, “Hell no! You’re trying to Westernize my child!” I was really sensitive to that right from the start, so I went out of my way to make sure it was just about a board with four wheels, and they were interpreting it in their own way and creating their own culture with it, so that it wouldn’t be seen as negative or as taking away their culture. It was really important that they developed their own culture around it and they did. They listen to Bollywood soundtracks on their little MP3 players and they wear Afghan fashion, which is influenced a bit by Iran and Pakistan.

So the girls skating the park would be wearing the traditional garb?

Yeah. They’d wear whatever they normally would wear.

That must have been so rad to see.

Yeah. It was really exciting for me to see this thing start to blossom in its own way. It was really important to me that these kids started to develop a new identity for themselves, because that’s something that all skateboarders feel. They’ve got a shared identity in skateboarding. These kids wanted to have some sort of new identity and the skateboarding community allowed them to do that. They started to develop their own stuff and their own slang and their own subculture. It wasn’t from America or Australia or anywhere else. It was just what was possible through this board with four wheels that is so much fun.

How does that mesh with the traditional Afghan people? Are they stoked because the kids are happy or are they mad that the kids are not following the same path as everyone else? Now those kids are skaters and all the other kids around them are not skaters. How is that seen from the parents?

I think it’s seen quite positively by the parents because we mix education with skateboarding from a very early stage. A lot of the parents see their kids going to school and learning stuff. We are pretty strict in terms of what sort of behavior is acceptable and what is not, so they are probably seeing their kids becoming more polite and more helpful and more civic-minded. The kids are getting educated on stuff that they didn’t know through just coming to Skateistan, so the parents associate skateboarding with their children gaining skills and becoming better adults. It’s more than just skateboarding. Skateboarding is just the big hook because we have this amazing skateboard park with brand new skateboards. We have marble floors, which is the best thing to skate on. It’s an amazingly fun thing to skate. That’s the big draw that gets the kids in there, but they are also learning other things at the same time. I think the parents see the change in the kids and they associate Skateistan with education.

Does anyone from the local government come by your place to see this representation of how kids are learning in Kabul?

Yeah. Whenever people have visited, they are super impressed with what’s going on there. There are not that many positive projects that work over all. When they see that the project is working and they see the smiles on the kids’ faces, they are won over straight away. They see it as something that is progressive and cool. Skateboarding didn’t have any baggage in Afghanistan, because it didn’t exist there before, so people didn’t know anything about skateboarding at all. It was this strange thing where people were just sort of gliding along the floor and they’re like, “What’s going on there? That’s pretty amazing.” You’ll never come across so many police that are down with skateboarding as in Afghanistan. Anywhere you go, and there’s a policeman, they’re not telling you not to skateboard. They’re trying to take your skateboard away from you so that they can try to skate themselves. Anyone that sees a skateboard is like, “Wow. That’s amazing. Can I try it?” There is no bad association with it all.

It’s all new to them and it just looks like fun. What’s the next project that you did?

The next town we went to was Phnom Penh in Cambodia. There was a guy, Benji, working there in an NGO and he wanted to build some ramps and we gave him $5,000 to build ramps. We helped him get skateboards and we gave him our curriculum for what we were doing in Kabul. Next, the German government wanted us to build something in the north of Afghanistan, in Mazar-I-Sharif, so we built a facility three times the size of the one in Kabul. That facility has a capacity for 1,000 kids weekly. It’s a skatepark and a multi-sports hall, so it has a climbing wall and kids can play soccer, cricket and volleyball. We’ve built this really cool thing out of shipping containers. We have 42 recycled shipping containers and we stacked them in all different ways and put this roof over the top and that holds our education facility and classrooms. We have a room with sewing machines so they can do sewing. We have a wood working shop so they can build chairs and fix skateboards. There’s all sorts of stuff in the Mazar facility.

What kind of skatepark is it? Did you build any roundwall or vert ramps or is mostly street stuff?

It’s pretty similar to Kabul. We’ve got a really high wall ride that’s 20-foot tall. That’s the Great Wall of Afghanistan, but no one has dropped in on it yet. It’s pretty big. There is no actual vert. It has tranny at the bottom and it’s this really big angle that just goes up at 75 degrees, but then it goes really high. On the other side, we have a really big roll in that’s about 13 feet high. Then there are different street obstacles and flat banks and a back to back mini ramp, so they can do roll overs and go really fast over that. The skateparks are based around making it really fun for a beginner. We want them to be able to get into it and roll around. We built an outdoor skatepark in Mazar-I-Sharif as well. It’s a plaza type thing that goes all around. We don’t really have any big round wall or vert ramp. I think we’ve got to build a vert ramp in Afghanistan. That would be a great addition. Our roof in Kabul is high enough, so we have the space to do it.

How sick would that be to see those girls dropping in on vert ramps and doing 8’ method airs and just blasting out?

That would be so sick. I think it’s time. We just have to work it out. The wood situation gets tricky because we imported all of the birch for the ramps. In Mazar, we found wood locally sourced. It wasn’t so good quality, but it’s still holding up. In Kabul, we imported all of that from Russia via Germany and that was pretty tricky.

What about concrete in that area?

Concrete could work. An indoor concrete skatepark would be great because you could skate it all year round. It’s a little bit trickier with dust, but we can look at what’s possible. The last school we built is in Johannesburg, South Africa. We opened that up and Tony Hawk came out for that.

How did that come about?

That came about through one of the supporters from the Danish embassy. The Danish ambassador went from Kabul to Johannesburg and he said, “If you ever want to do something in South Africa, let me know. I can probably help you out.” We thought South Africa would be a good idea because it’s a big melting pot, and it would be a place that is a bit more stable. Phnom Penh and Afghanistan are pretty crazy places to work and we wanted to see if we could build something in Johannesburg and improve our programs by doing something in a less chaotic environment. Hopefully, that would then trickle down and end up improving what we’re doing in Cambodia and Afghanistan. I also was contacted by a guy, Simon Adams, that worked heaps with the ANC in the early days and the fight against Apartheid. He had lots of experience and he knows lots of foreign ministries. He now works for Responsibilities To Protect in New York, which was set up by Kofi Annan after the Rwandan Genocide. Simon works with genocide issues all over the world, and he got in touch and said, “If you ever want to do anything in Africa, let me know. I can help.” He was a skateboarder from the ‘70s and he used to skate Lakewood in California. He’s a super rad guy. Now he’s doing this high level stuff. He and I went to Johannesburg and did this scoping trip and he was like, “This can definitely work out.” So we got some land and we built again with recycled shipping containers. We built a concrete skatepark and the guys from Canada, New Line, came out and helped build that skatepark.

What do you have in that park?

It’s similar to our other parks with some bigger quarter pipes. It’s a mix of transition and street. It’s stuff the kids can roll around on and learn.

What was the reaction from the local community in Johannesburg?

There was a lot of anticipation about it. It was something that was different from other places we were. They already had a skate community, so they were kind of weirded out by what we were doing.

Why were they weirded out?

I guess it’s our mix of skateboarding and education and the fact that we exist in Afghanistan. They were like, “We’re not a war zone. What are you doing here?” They heard we were building a skatepark and they were like, “When can we skate the skatepark?” We had to explain that we were building it for Skateistan students. I was surprised that we didn’t get more skateboarders trying to help us develop programs over the last two years in South Africa. It was other people that got it and thought it was a cool thing and wanted to help. There were only one or two core skateboarders. One of those core skateboarders is actually the best female skateboarder in the whole African continent. She has been driving a lot of stuff now that we’ve got the park and it’s a big magnet. It was different attracting people to the program there. In Afghanistan, the kids don’t have any other options, so they have such a hunger for knowledge and they have such a harsh existence that anything you provide them, they take it to the max and really utilize it.

Is it the same way in Phnom Penh?

Cambodia was pretty similar. People were pretty crazy about it. There was a little skate scene and some of those guys would help out, but not so much. In Johannesburg, it was almost like the kids had other options. It was surprising from that point of view. I guess what I’m saying is that Skateistan works best in the harshest environments that have the least stuff.

Are you getting enough kids in Johannesburg to keep it going?

Oh yeah. They are absolutely overwhelmed because everyone is so excited about the skatepark and the opportunity to learn and be part of Skateistan. I think it’s just a matter of making the curriculum super interesting to them and showing them that school is fun. That’s the key part of it.

It’s brilliant and it sounds like it’s working. You had Tony Hawk out there for the Grand Opening, right?

Yeah. He came to Phnom Penh a couple of years ago and then he agreed to join our advisory board, so that was really cool. He has been super helpful with getting support and we’ve been able to do lots of things. Tony has been amazing. He’s such a down to earth guy and he’s showing us a lot of love.

When Tony showed up in Cambodia, what was the reaction of the locals?

People were in awe. He set up two big quarter pipes about 10 feet apart and ollied the gap first shot. We have a concrete vert wall with transition. It’s about 8’ tall, but it’s got tons of vert on it, so it’s hard to get up there. Tony was doing scratch grinders and backside disasters on that. Other people haven’t even gotten to the top and he was doing all these lip tricks on there, so that was sick.

You’re in Cambodia, South Africa and Afghanistan bringing skateboarding to the kids and you’ve got Tony Hawk coming there to skate. Is it surreal for you?

It’s totally surreal. I can remember myself as a 12-year-old kid saving up for eight months to get a certain board of your hero. To me, it was Caballero. Whatever he was doing, I was following it. Now I’m starting to work together with these people. I was invited to be on the board for the Tony Hawk Foundation, and it’s like my wildest dreams when you think of how much of a fan you were as a kid. Even you interviewing me, I don’t feel like I deserve it. I didn’t really earn my place in any way. I’m just doing my thing and putting things together.

You’ve more than earned your place. You’re saving lives with these skateparks.

I’m just glad that I can give back to skateboarding in some way because it’s such an incredible force in my life in terms of introducing me to amazing people around the world and to music and all these different friends for life. It’s like this thread from the time of my dad dying. I’ve never been so good at skateboarding, but it’s been the thread that’s always been there for me. Skateboarding is an amazing thing to be able to give back and be able to do.

Do you ever think how crazy a thing like a skateboard is and what it can do for kids, and how in the gnarliest places in the world, it can be a key to happiness?

Yeah. I think, “Why does it have to be skateboarding? Could it be something else?” I always come to the conclusion that it couldn’t be anything else. I got it when I was five years old. I understood it within the first ten minutes of standing on a skateboard. I’d seen pictures of other people doing it and I really thought it was going to be easy. I was rolling along and thinking I was good at it and then I fell flat backwards and I was almost seeing stars. I clearly remember thinking, “I’m going to master this thing. I’m going to work out how to do it.” It’s a beautiful metaphor for life. You have to keep trying to get better at it and make what you can of it.

Totally. Where is the next low resource area that you’d like to see Skateistan go?

I’d like to build an enormous skatepark in the Zaatari refugee camp on the border of Syria in Jordan. It has 80,000 people in the camp and I want to build a massive skatepark and school there. I think that would be amazing. I think we really have to take action on refugees, especially from Syria, because they have such a tough situation. From there, I’d like to be on all of the continents.

Do you have any connection in Syria to try to build that dream?

Yeah. We’ve got some contacts, so I’ll look into what’s possible there. Maybe we can build something like we did in Afghanistan that has the capacity for 1,000 children weekly, with skateboarding and education. I think that’s exactly what those refugee kids need. The word refugee has become a negative word. I mean people were taking in refugees after the Second World War from Czechoslovakia to England and that was seen as something positive because they were saving them from the Nazis. Why was it such a positive thing then to take in refugees and it’s such a negative thing these days? It’s crazy. I really want those kids to have an identity. In the Middle East region, 80% of the population is under the age of 30. They don’t have good educational opportunities and they don’t have job opportunities, and the world puts itself in peril by ignoring them and not giving them opportunities. We need to engage with young people in that part of the world and bridge some gaps, especially between the Muslim world and the West. I think skateboarding can save the world.

If you built Skateistan in a Syrian refugee camp, that would be great for those kids.

I think it would be amazing. I hope that I can raise the money to do something like that. We’ve done all these things so far, and having had a lot of success on the ground in Afghanistan should help. We’ve had success where other much bigger organizations have not and weren’t able to gain the results that we did. The difference was that we were skateboarders and they weren’t. The difference is building community. We’re able to build a genuine community through skateboarding and that genuine community then creates results. It comes back to what I was talking about with the Aboriginals in Australia, in terms of matching social capital with financial capital in order to get results. That’s the difference. We didn’t have money at first, but we built a community and slowly got people to put money in. Once there were friendships and trust had been built, the community started to develop. You can’t put in the money before you’ve got the community. It’s not going to work. The money is just going to disappear. You have to build the community first and then put the money in. On one hand, that’s the challenge but, as skateboarders, I think we can create community in a place like the Zaatari Refugee Camp. I think it can work.

What would the ground plan be for Syria?

The first thing would be a scoping trip. I’d go there and try to meet with as many people as possible, like government people, community leaders and the kids. I’d bring skateboards and show people what skateboarding is and try to find some local leaders and young people that are ready to take on the project on the ground. You try to get an equal amount of women and men behind it from the start, so it’s not just a male-dominated thing. From there, it would be trying to secure land and then having a look at the building company that could build a facility. Then we’d try to engage some skatepark builders to help us build it. We’d need to have the money and land in place and the okay from the politicians. I think the politics gets pretty gnarly in a refugee camp. I’m sure there are local forces that are running stuff and, if you don’t cut them in, they’ll start causing havoc for you. I’m sure there will be some politics to navigate. I think it’s about finding some local champions that get it. Maybe there are some Jordanians that skate that would be ready to bring other people into the fold. Then we would find one or two international ex-pats that have been involved with Skateistan for a long time that understand how to build things up and we would have them on the ground for a few months doing skateboard sessions. Maybe they could bring some kids from the refugee camp on buses to the closest skatepark in Amman and take some photos so they can show their parents and their community what we want to do. Then we get the kids that are skateboarding to champion it too. What we did in Johannesburg was that we ran skateboarding sessions at a local skatepark for two years while we were doing our build. We were doing some education sessions as well. At the same time, you’re trying to do your build. Once you start the build, the kids that have been skating can get involved with building the skatepark too. That ownership part is super important to to the sustainability of it. If you go in and just plunk something down and expect people to use it, it’s not going to work. You have to make them work for it a little bit. You can have the best idea in the world, but if they don’t really want it, it won’t work. I get the feeling that with 80,000 kids in a camp with nothing to do, a huge skatepark would be incredible. It could make a massive difference.

It’s a solution for the kind of world that we live in now. You have to grow it worldwide. What’s your duty now for the future?

One thing is keeping on to those hard fought wins that we’ve made so far and not letting those things slip between our fingers and making sure that we retain everything we’ve built up so far with Skateistan and then grow it. I see so much potential. I see it as a way to create links between everybody around the world. In so many places, there are more and more people trying to create a vision between people. I think skateboarding can bridge that in some respects and I want this to go bigger. The other part is that skateboarding is going to get bigger anyway with skateboarding going into the Olympics in 2020. Other people are going to jump in there and try to do stuff with skateboarding and that’s dangerous. I want to bring it back to the skateboarding that I grew up with where it was such a tight crew. It didn’t matter if one person was into heavy metal and the next person was into hip hop and the next person was into punk rock. We all saw ourselves as skateboarders. Somehow we were all banded together and we didn’t really care about the color of somebody’s skin. All of a sudden, it didn’t matter what you were like, if you were an introvert or extrovert or whatever, you could be part of the scene. I really want that aspect of skateboarding to be retained. You’re making connections with friends all over the world through skateboarding and part of my responsibility, in terms of being able to do things through Skateistan, is I really want to retain that aspect of skateboarding where you see another skateboarder walking down the street and you don’t ignore them, you say hi to them. You make a connection. That’s something that we’re losing more and more in society. Everybody is so absorbed in their own little world, or on social media, or hiding away in their house watching movies or doing things online. People have lost the ability to make human connection and I think skateboarders should be the ones that retain that aspect of skateboarding that is real, where you’re real with someone else and it doesn’t matter where they come from. Back to your question of my duty, I’d say, I’m trying to keep skateboarding as real as possible.

That’s great. That’s what we all have to do. How can people donate and help you grow Skateistan?

They can donate at https://skateistan.org/

FOR THE REST OF THE STORY, ORDER ISSUE #75 AT THE JUICE SHOP…

SHARE THIS POST:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)