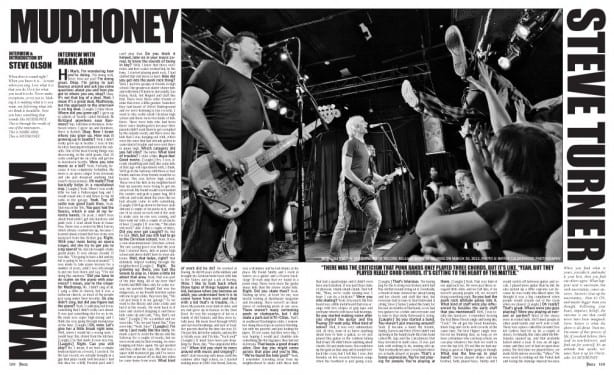

MUDHONEY

INTERVIEW & INTRODUCTION by STEVE OLSON

PHOTO BY NIFFER CALDERWOOD

MARK ARM: When does it sound right? When you know it is… Scream when you sing. Love what it is that you do. Do it for what you need it to be. Never make exceptions, or try not to. Making it is making what it is you want, not following what others think it should be. Now you have something that sounds like MUDHONEY. This is through the words of one of the innovators… This is MARK ARM. This is MUDHONEY. – Introduction by Steve Olson

STEVE TURNER: When you find what is yours, you take it, and make it your best, then you find out others agree. What happens next is uncertain, but with uncertainty, comes answers. Answers clear up the uncertainty… then it’s ON, and maybe bigger than you thought. Following your heart, impulses, beliefs, the outcome is one that could never have been imagined. Steve Turner is what the above is all about. Trust me, I’m aware of this process of life, if you don’t believe, then read on non-believers, and find out for yourself. It’s an attitude that speaks volumes. Turn it up for Christsake. – Introduction by Steve Olson

===========

INTERVIEW WITH MARK ARM

Hi Mark. I’m wondering how you’re doing.

I’m doing well, Steve. How are you?

I’m doing great. Okay. I’m going to just bounce around and ask you some questions about you and how you got to where you are, okay?

Okay.

It’s not that big of a deal. Wait. I mean it’s a great deal, Mudhoney, but the approach to the interview is no big deal.

[Laughs.] Okay Olson.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in suburb of Seattle called Kirkland.

Is Kirkland anywhere near Kenmore?

Yep. I did time in Kenmore. In between where I grew up and Kenmore, there is Bothell.

Okay. Now I know where you grew up. How was it growing up in Seattle?

Well, I didn’t really grow up in Seattle. I was in this faceless housing development in the suburbs. One of the most freeing things was discovering, in the sixth grade, that 35 cents could get me on a bus and get me to downtown Seattle.

Were you into music as a kid?

Yeah. Partially, because it was completely forbidden. My mom is an opera singer from Germany and she just despised anything that wasn’t classical music.

Oh really? That basically helps in a roundabout way.

[Laughs] Yeah. When I was really little we had a Volkswagen bug and I would sneak into it and listen to Top 40 radio in the garage.

Yeah. Top 40 radio was good back then.

Yeah. That was in the ‘60s.

You guys had the Sonics, which is one of my favorite bands.

Oh yeah. I didn’t hear about them until I got into hardcore and punk rock. I read about them in Trouser Press. There was a review by Mick Farren, which always cracked me up, because I learned about a band that was in my own backyard from this British guy.

“There was the criticism that punk bands only played three chords, but it’s like, “Yeah, but they played really good chords. It’s getting to the heart of the matter.”

Right. With your mom being an opera singer, did she try to get you to sing opera?

No. But she bought a baby grand piano. It was always around. It was like, “I’m going to have a kid and my kid is going to be a classical pianist.” I was made to take piano lessons for a number of years, until I was old enough to put my foot down and say, “I’m not doing this anymore.”

Did you have to do scales on the piano with your voice? I mean, you’re the singer for Mudhoney.

No. I didn’t sing at all. I sang a little in church, but it was a Lutheran church, so most of the people just sang under their breaths.

So you didn’t sing, but did you figure out the piano?

Yeah. I could play, but it was something that I didn’t really care about. It was just something else for us to do. My mom was super high-strung and I think she was going through menopause at the time. [Laughs]

Oh, wow. Let’s give her a little break right now.

Well, when I would hit a wrong note, I would hear this shriek from the kitchen. [Laughs] So that made it even less fun.

[Laughs] Right. Can you still play?

No. I mean, if we have a simple keyboard part on a record, I can do it. On the last record, we actually brought in a guy that plays really well because I had this idea for a Billy Preston part and I can’t play that.

Do you think it helped, later on in your music career, to know the sounds of being in key?

Well, I knew that there were notes and how scales worked but, by the time, I started playing punk rock, I had stuffed that shit down so hard.

How did you get into the punk rock thing?

Well, I had two groups of friends in high school. One group was skater stoner kids and with them I’d listen to Aerosmith, Van Halen, Rush, Ted Nugent and stuff like that. There were these other friends of mine that were a little geekier. Somehow they had heard of Velvet Underground and we were listening to Eno records. I went to this really small Christian high school and there were two kinds of kids there. There were kids who had been there since kindergarten because their parents didn’t want them to get corrupted by the outside world, and there were the kids that I was hanging out with, which were the ones that had already gotten in some kind of trouble and were sent there in junior high.

Which category did you fall into?

The latter.

What kind of trouble?

I stole a bike.

Bicycle Thief. Good movie.

[Laughs] Yes. I was already shoplifting and stuff, like some kids at that age will experiment with, I think. We’d go to the Safeway with three or four friends and one of my friends would be so brazen. This was before high school. These were the kids in my neighborhood that my parents were trying to get me away from. My friend would reach behind the counter and grab a paper bag, fill it with air and walk about the store like we had already come in with something. [Laughs] We’d go down to the beer aisle and put a couple of six packs in it, while one of us stood on each end of the aisle to make sure no one was coming, and then walk out with a couple of six-packs of beer. [Laughs] It was like, “This plan will work.” And it did a couple of times.

Did you ever get caught?

No. Not for that.

Well, but you still had to go to the Christian school.

Yeah. It was a non-denominational Christian school. The one saving grace was that the year that I started there, kids in junior high school and above didn’t have to wear uniforms.

Well, that helps, right?

That definitely helped walking through the neighborhood.[Laughs]

Right. So growing up there, you had the woods to play in. I know a little bit about that area.

Yeah. That was part of the bike thing. All of my beer thief friends had BMX bikes and, for some reason, my parents thought that was too dangerous, so my friends hatched a plan with me to get a bike. They were like, “We can just keep it in our garage.” So we went to the library and stole a bike and hid it in the woods. We went back to it later and started stripping it and these kids came up and said, “Hey, that’s our bike.” [Laughs] We scrambled and we were like, “Oh, we just found this.” They were like, “Yeah. Sure.”

[Laughs] I’m sorry. I just really like this story.

We made a pact to avoid the library and the Safeway for a couple of weeks, but we were weak and, by that evening, we were hanging out there again. We got spotted and they called the cops. My dad was a super mild-mannered guy and I’ve never seen him so pissed off as that day when he came home from work.

What kind of work did he do?

He worked at Boeing. He did 20 years in the military and brought his German bride back with him to the States and got a job at Boeing.

Wow. I like to look back when those types of things happen as a kid, because when you become an adult, you understand how it is to come home from work and deal with a kid that’s in trouble.

Oh, I know. My parents were kind of older and my dad grew up in Kansas in the Dust Bowl. He was the youngest of ten in a family of dirt farmers and they were totally poor. My mom lived through WWII and survived bombings and lack of food. Her parents died by the time she was 19. I’m just this kid in the suburbs and my life is totally easy and I’m like, “Fuck you!” [Laughs] It must have been jaw-dropping for them, like, “You ungrateful little shit.”

When did you start to mess around with music and singing?

I didn’t start messing with music until the summer after high school, so I started making noise in 1980. Our friend, Darren, was a drummer and he had drums at his place. My friend Smitty and I went in halves on a guitar and a Peavey backstage 30-watt amp that we found in a pawn shop. These were more the geeky music kids than the stoner skater kids.

Right. Did you skate then?

Yeah. Skating up here, at least for me, was mostly looking at Skateboarder magazine and dreaming. There weren’t an abundance of swimming pools in our area.

There weren’t many swimming pools or skateparks, but I did skate a park out in Tri-Cities.

That’s in southeast Washington state. I remember doing these trips in eastern Washington with my parents and just looking for pipes. I’d see some, but they were tiny. I was hoping I would just stumble into something like the big pipes they had out in Arizona.

That keeps a good dream alive. One day you might come across that pipe and you’re like, “We’ve found the holy grail!”

Yeah. I remember traveling away from my neighborhood to skate with these kids that had a quarterpipe and it didn’t even have any transition. It was just three slabs of plywood, chunk-chunk-chunk. That felt like, “Man, we’re really skating now. I hope I can do a kickturn.”

Were you into skating?

Yeah. Very much. My first board was a little metal board that was orange with two stripes of grip tape and urethane wheels with loose ball bearings.

So you started making noise after you shared the guitar and the Peavey 30-watt amp. What kind of noise?

Well, it was very rudimentary shit. At first, none of us knew anything about how to tune a guitar, so we just played this guitar in the random tuning that it had. We didn’t know anything about chords. We just made noise. You could turn up the gain on that amp and it would feedback like crazy, but I felt like I was Jimi Hendrix on live records between songs when the feedback is just going crazy. [Laughs]

That’s hilarious.

The tuning peg for the A string was broken and it had this old flat wound string on it. Eventually, a friend of mine showed me about tuning and bar chords and stuff like that, but everyone had to tune to that flatwound A string. Steve [Turner] joined the band, for the last six months of that band, so we had two guitars for a while and everyone and to tune to that shitty flatwound A string.

“After getting into punk rock, Ted Nugent and KISS sounded a little weak to me. Then you compare Nugent to the MC5s or the Stooges and it’s like, “Hack.”

[Laughs] So you started a band. You weren’t just messing around?

Yeah. It became a band. My friends, Smitty, Darren and Peter (Peter didn’t end up being in the band) made this fake band called Mr. Epp and the Calculations that they invented in math class. It was just kids with nothing to do, making shit up. That eventually became a real band where we actually played at people.

That’s a funny expression. You’re not playing for people. You’re playing at them.

[Laughs] Yeah. That was kind of our approach too. We were just these arrogant little shits and we felt like, if we weren’t pissing people off, we weren’t doing something right.

So you had the punk rock attitude going into it. What kind of stuff were you influenced by besides the early stuff that you mentioned?

Well, I was totally into hardcore. I remember hearing the first Minor Threat single and being like, “Fuck.” We all got the Dead Kennedys, Black Flag and Circle Jerk records at the same time. The first Flipper single reinforced my thinking that, as long as we have a drummer who can keep a beat, we can play whatever the fuck we want to over the top of it. It’s not like we had anything as good as Flipper going on though.

What was the line-up in your band?

Darren played drums and his brother, Todd, played bass. Smitty and I would switch off between guitar and vocals. I played more guitar than he did. He also picked up a little soprano sax because he was really into Albert Ayler. We thought it was a big compliment when people would stream out of the room when we played. [Laughs]

Oh really? That’s great. Where were you guys playing? Were you playing at venues or parties?

Most of the shows were in rented halls. We’d meet people in other punk bands and we’d rent a hall. There was a place called the Ground Zero Art Gallery that let us do a couple of shows. Eventually, this club called the Metropolis opened up, and that probably lasted about a year. It was an all ages venue and they sort of had an open-door policy. The first time we played there, we made $100 and we were like, “Whoa.” We were used to renting out the Polish hall and losing the damage deposit because someone destroyed the toilet.

What kind of music do you think it was that you guys were making? Was it hardcore or punk rock or what?

I don’t know. We were totally into punk rock and we were into some industrial shit. Todd would say his favorite bands at the time were Black Flag, Throbbing Gristle and P.I.L.

That’s a crazy combination.

You’re out in your own little world trying to figure shit out. We weren’t the cool kids in the punk rock scene, so we didn’t know what you were supposed to like.

How long did Mr. Epp and the Calculations continue to play?

We stopped in ‘84. I think Darren, the drummer, thought it was getting too rock or something.

What does that mean it was getting too rock?

Well, our crap wasn’t normal rock. By this time, I had learned chords and we were writing stuff that was a little more structured. The Stooges had become a huge influence for me. Those guys liked them too, so I’m not quite sure.

What happened after Darren said, “You guys are too rock n’ roll. I’m out of here?”

Steve had joined the band six months before that, so we started writing two guitar songs. We wrote this whole new batch of songs, and maybe Darren didn’t dig that new batch of songs. We played two shows with Steve. One before we knew we were going to break up and one after, like one last hurrah thing. It was kind of crazy because we had been reviled locally. Everyone was like, “Fuck those guys.” But we had made friends with these other outsider kids who were into punk rock from Federal Way, which is a suburb way in the south. It was these guys in a band called Limp Richerds, and it was other people that didn’t think they fit in with the leather jacket, spiky hair crowd.

Was it an outsider scene when you first started doing it, where everyone was into that movement of punk rock up there?

For sure. It was such a small scene up here. I mean no one got beat up for having long hair or a mustache or anything like that. It’s not like what was happening in California where people were getting pinned to the ground and getting their heads shaved or whatever.

That did happen, but that was only because the sun was shining. [Laughs] It’s a joke.

[Laughs] There were people who were older than us, and I learned about the roots of that stuff later. Around the early ‘70s, before punk rock came along, there was a group of people that were involved with these theatrical productions and musical things called Ze Whiz Kidz. They were sort of aligned with the Cockettes in San Francisco. Tomata du Plenty was part of that group of people. He and Gorilla Rose started the Screamers in L.A., but before that they had a punk band up here called The Tupperwares and they played the first punk show in Seattle with the Telepaths and Meyce. We’d go see bands like the Refuzors and they were maybe four or five years older than we were, but they seemed like they were in a whole other generation. I’d hang out at Rubato Records in Bellevue with the Mr. Epp guys in high school. We all went to Bellevue Christian. The people who worked at Rubato were older and they were in bands that were more new wave, but they pointed us in fantastic directions. They realized that we were curious about stuff, so they would say, “Hey, here’s Ornette Coleman and here’s the New York Dolls.” We were like, “Oh, okay. Cool.” John and Helena, who owned Rubato Records, invited us to open for their band, Student Nurse. I don’t think they’d even heard us. That was the first show Mr. Epp played.

“I was like, “You’re putting us, who are barely known, and Tad and Nirvana, who were unknown at this point, in the Moore Theatre. I was like, “You’re going to lose your shirt.”

Oh nice. How long was the Mr. Epp first set?

Fuck if I know. We were making noise at Darren and Todd’s house and when we started talking about playing for the first time, Darren got cold feet because he could actually play and he didn’t want to embarrass himself with a bunch of people that didn’t know what they were doing, so he quit the band for a little while. We got this guy that worked at the record store to drum on the very first show and then Darren was like, “This is stupid. I can do this. I’m in.” He was like, “Who am I worried about being embarrassed in front of?” Darren went on to play, with the band, Steel Pole Bath Tub. They released a couple of albums on Boner Records, one on Slash and did a split single with the Melvins. This is in the late ‘80s to mid ‘90s.

Nice. Are you still in touch with any of your friends from Mr. Epp?

I’m in touch with Smitty. In fact, about two months ago, Steve and I played in this band called the Thrown Ups. The whole premise of that was that you get drunk and write a set list and think up the funniest song titles you could think of and then play the set in front of people. There was no practice.

Oh right?

Our friend, Ed, was the singer in that band. There have been a couple of people who cycled in and out of the Thrown Ups and one of them organized a jam session for everyone and Smitty came out for that. That was great fun. I saw a couple of people that I hadn’t seen in 15 years. We were just in my friend’s basement making noise on the spot.

After you guys broke up Mr. Epp, what happened?

Steve and I wanted to keep doing something, so that’s when we tried to figure out who to play with. Our friend, Alex, played drums so we figured we had a core of a band right there.

Was Steve on bass then?

No. He was playing guitar. We didn’t know Jeff Ament very well, but we had seen his band, Deranged Diction. He played with a distortion pedal, jumped really high and we figured that he would be great to play with. To get to know him, Steve actually got a job at the same place that Jeff worked. [Laughs]

No way. Come on.

[Laughs] Yes. Jeff was in a band that was still playing shows, so you couldn’t really say, “Hey, man, do you want to quit your band?”

And come join our band.

Yeah. He actually hated Mr. Epp. He thought we were horrible, but I think he thought, “Well, they’re obviously motivated and they want to do something.” At that time, other members of Deranged Diction, maybe the drummer would flake out like, “Well, I don’t feel like practicing today.” You know how that kind of shit goes.

That’s disheartening.

Yeah. Right after Mr. Epp, my guitar equipment took a crap and I didn’t have any money to get a new amp, so Steve and I started trading off. He played guitar more than I did, but he sang on a couple of songs. That was the very beginning of Green River. A little while later, we added Stone on second guitar. A little while later, Steve quit.

Why the name Green River?

Steve and I both thought of the name on the same day. There was the Green River killer thing going on up here at the time. Steve had just found a Green River Community College track t-shirt at a thrift store. I don’t know how I arrived at it, but later that day we ran into each other and both said, “I think I’ve got a name for the band.” At the same time, we both said, “Green River.” We said, “Okay, that’s got to be it.” It sounds innocuous, but it was really offensive to people around here at the time.

Was there any grief because of the whole Green River name?

Not really. We played one show opening for the Crucifucks and the Dead Kennedys and someone said that there was a woman’s group outside protesting Green River, but I never saw that. I didn’t see anybody marching around with signs.

So you had Stone and Jeff and you. Who was the drummer for Green River?

Alex. He was a friend I met going to punk rock shows. Steve, Alex and Stone all went to the same high school.

This was way after high school right?

Yeah. This was 1984, so it was four years after high school for me. It was maybe a year or two after for Steve, Stone and Alex.

You’re ready to go attack the world, so why did Steve quit?

He didn’t like the direction the music was taking. We were getting into different stuff. Metallica’s first record had come out and Venom and he thought that shit was just stupid. We were experimenting. Venom is stupid, but they are great and hilarious at the same time. Steve just didn’t see the humor in it. He was super into the Sonics and then he got into Thee Milkshakes and all that Billy Childish stuff. He wanted to play simple bare bones rock n’ roll and we were writing songs that had way too many parts. At that point, I think we were just trying to stretch our abilities. This was around the time we did the first record. There’s one song on it that has probably nine parts and nothing really repeats the same way twice. Steve was like, “I never knew how to play that song. I was just standing in place pretending.”

I love that. [Laughs] Were you singing in Green River?

Yeah. Steve quitting was kind of a wake up call. One thing I learned from going through that process was that just because you can do something, doesn’t mean you should. We stripped things back down after Steve left. The initial thing with singing, and this might make it sound better than it was, but I was just barking and hardcore growling. There are demo tapes from that era, before Stone played with us, and those vocals are horrible. I don’t know what I was thinking.

[Laughs] When Stone came in, did it make you sing better?

No. Not at all. There was just a realization that we were getting out of hardcore and expanding our horizons. We were really getting into Alice Cooper and Black Sabbath, and stuff that I had missed because I was too young or because I didn’t have an older brother. Do you know what I mean?

I know exactly what you mean. Having an older brother sometimes opens the horizons to a younger brother’s limited view.

Right. I mean I can only imagine because I’m an only kid, but a lot of kids were listening to stuff that their older siblings were listening to, and that’s how they found out about it.

Yes. How long did Green River last?

We broke up in ‘87, so it was three years.

So you guys were playing gigs, obviously.

Yeah. The first show was at a party. The second show was at this weird space near Ground Zero Art Gallery and Graven Image Art Gallery that these punk dudes had rented out and built a stage in. There was a Port-A-Potty in it called the Grey Door. It was a totally unlicensed spot, and the Port-A-Potty was never cleaned, but it was in a part of town that no one gave a shit about. Now it’s a total high dollar area. We knew the main punk rock promoter guy pretty well, so he would put us on shows with the Dead Kennedys when they came to town. We got on a show with Black Flag and clearly, Black Flag was their own touring group with Saccharine Trust and Tom Troccoli’s Dog. They probably did not want us added to the bill. [Laughs] We also opened for Sonic Youth the first time they came to town. It was just crazy, weird happenstance stuff.

Were you nervous playing in front of people when you first started?

Oh shit yeah. I was.

Oh good. I was told that when you lose that nerve, you lose that immediate rush, and then it becomes like a job or something. I don’t know. So why did Green River break up?

I guess the easy answer is that if you ever heard Mother Love Bone and the first Mudhoney single, that would kind of sum it up. The last tour we did was a West Coast run down to California. I remember playing at the Chatterbox in San Francisco and it was a fuckin’ great show. We did a Tales of Terror cover and we had played with Fang in Seattle, so guys from those bands were there. We finished our set and we got asked to play more, which didn’t usually happen. I screamed way too hard and lost my voice a little bit. I remember Stone suggested that maybe I should take vocal lessons. I was like, “Fuck it. I just want to have my own style. I don’t want to learn the right way to do something.” Maybe vocal lessons would have kept me from burning out my throat though.

Or maybe learn how to breathe.

Well, I had already learned that from my mom. She was always telling me to breathe from my diaphragm. That was the one thing that stuck.

Oh that’s cool. Even in menopause, she gave you good direction. She was breathing from her diaphragm.

[Laughs] Yes. She was like, “I have to breathe from my diaphragm to keep from striking you, young man.”

[Laughs] Exactly.

The next night after San Francisco, we went down to L.A. and played this gig at The Scream opening for Junkyard and Jane’s Addiction. At that point, Jane’s Addiction wasn’t that big outside of L.A., but they were definitely big in L.A. I could barely croak out a tune. Stone had already been playing with Andy [Wood] from Malfunkshun. He was just helping Andy because he had an idea of doing something a little bit different than what Malfunkshun was capable of doing. We came back from that tour around Halloween and we all got together for practice and Stone, Jeff and Bruce broke the news to Alex and myself that the band was no longer. I actually felt really relieved.

Why so?

Because the band was going in a direction that I wasn’t super comfortable with. If you hear the very last Green River record, the production on it had that big giant ‘80s snare sound. I was like, “That sounds so bad.” At this point in time, everyone agrees that it sounds bad but at the time they didn’t. They were like, “Well, this is what rock records are supposed to sound like nowadays.” I was like, “I hate this.”

Oh, that’s annoying, when you just want to get your sound across.

Well, I never wrote any music in Green River, except the very early stuff that never made it out of the demo stage or the first recording stage, so my input was limited.

When did you start recording Green River stuff?

The first demo, before Stone, was really early on. We just whipped up a batch of songs and went in and recorded an 8-track with this guy, Chris Hanzsek. Then we whipped up a second batch of songs with Stone on guitar that were a lot more complicated and made Steve feel uncomfortable. We recorded that stuff in ‘85 and we planned on doing a tour in the fall of ‘85 and that’s when Steve was like, “Oh crap, they want to go on tour. I don’t want to do this anymore.” [Laughs] That tour was really funny. I remember we each saved up around $700, piled into a car with a U-haul and drove across the country and played seven shows. There’s a shirt that Jeff made with the 20 shows that were supposed to happen and we ended up playing seven shows. One of those was a show we picked up while we were just hanging out in Columbus, Ohio, because we had nowhere to go. We played a show and then hung out a little bit and then Decry came through town and somehow we got on the bill with them.

Was Green River part of Sub Pop?

Yeah. The first record was on Homestead. When we came back from our first tour, we wanted to release a single and we asked Bruce Pavitt, “Would you be interested in releasing this?” He had just put out the Sub Pop 100 Compilation and he was like, “I have no money whatsoever right now, but I’ll totally help you guys in guiding you through the process of getting a record pressed and all that stuff. By the time we did our next record, which was a five-song 12-inch, both Bruce and Jonathan at Sub Pop decided to release it. Then they released our last record, the one with the horrible drum sounds. Apparently, we were their flagship band, which ain’t saying much, because there were only two or three bands on the label then. The Fluid was on the label and Soundgarden had just left for SST. We were the band that had actually gone on tour a couple of times, and we came back and the record was about done. Then we broke up. They were like, “Great. We have a record by a band that doesn’t exist.”

[Laughs] No support tour for that one. So Green River had some success, no?

No, not really. We had some success locally. As far as getting out of town, there were a couple of good shows in Portland and Vancouver and that last show at the Chatterbox in S.F.

Green River was playing in front of people though. That’s what I mean by success. It’s not like having a Top 40 hit.

Yeah. We didn’t make any money or anything like that, but we got to play on a lot of great bills. One of the funny things about Seattle bands, at the time, we deferred to bands from out of town. We would open up for them, even if they were less well known than we were. Our take was like, “Oh, they’re just coming through. This will give them an opportunity for more people to see them. We play here all the time.” There was this feeling that if that band was from San Francisco maybe that meant more than being from Seattle. We deferred to the Sea Hags when they came through town from the Bay Area, and no one knew who they were. Then we’d go down there and play a show with them down in San Francisco. We were the opening band, so we would play when no one was there. It was like, “Okay, thanks, dudes.” We didn’t realize that’s how things normally worked in other towns.

Live and learn. So you guys break up and Jeff, Stone and Bruce are going on to do something else and Steve has already split.

Yeah. Steve was actually going to school up in Bellingham. Instead of practicing that night, I remember going to the OK Hotel and getting fuckin’ hammered and running into Dan Peters in line for the bathroom. I was like, “Oh, dude. I have to throw up. Green River broke up.” I was kind of ecstatic about it. He remembers that. He thought I seemed kind of jazzed. I got in the bathroom and vomited. I called Steve the next day up in Bellingham and told him that Green River broke up. I said, “What are you doing? Do you want to start another band?” He had actually been playing a little bit with Dan, so that’s how this thing started. Within a month or two, I started playing with Dan and Steve. The Melvins had moved to San Francisco and left Matt behind, so we contacted him. That became our band. I’ve always been lucky. I’ve never been in a band that had to put an ad in the paper looking for people. I’ve always started bands with friends.

It sounds like there was this incestuous thing going on where these guys were going out and playing with other bands and making other bands with other guys from other bands.

Yeah. There were all kinds of permutations of different people and different bands, some of which, you’ve heard of and some you haven’t. Somehow this particular combination for this band stuck.

Right. Where do you think you got your vocal style from?

Two of my favorite singers are Jerry Rosalie and Iggy Pop, so probably a combination of those two.

What drew you to those two types of vocal styles?

I like screaming. [Laughs] Jerry Rosalie does it better than pretty much anyone. There is kind of a range, but also a limitation, with Iggy. On the first Stooges record, he just sounds bored. On Fun House, he’s just screaming and he sounds out of his mind. On Raw Power, he’s goes between the two, back and forth, and by The Idiot, he’s crooning. He has his own voice that’s totally distinguishable.

Yeah. When you hear Iggy, you know it’s Iggy. When you hear Mark Arm, you know it’s Mark Arm.

Well, I do. [Laughs]

What was your attraction to Alice Cooper?

By the time I got into Alice Cooper, it was after his new wave phase. When I got into early Alice Cooper, it was just purely the music. It had nothing to do with the theater. Terry Pearson, who was Sonic Youth’s sound man on the Daydream Nation tour, moved to Seattle and did a couple of tours with us. I remember talking with him about Alice Cooper. He was older than us, and he was way into Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s and he would buy anything that came out on Straight Records. For him, Alice Cooper was a joke. It’s just a weird matter of perspective. For him, that was like kiddie music, but I love the Alice albums on Straight, especially Pretties For You.

If he knew what Zappa was up to, Alice Cooper would be a joke.

I don’t know, man. I’d rather listen to Alice Cooper any day. There is some amazing playing on those Alice Cooper records. Dennis Dunaway is a phenomenal bass player.

A lot of those cats were great players. It’s almost like you had to be a great player to play in that arena of musicianship.

I don’t know. You had KISS. Peter Criss is probably one of the worst drummers to ever make hit records.

Yeah, but he could get away with it. I kind of loved New York Groove, but that’s just me.

Did he even play on that? Isn’t that an Ace Freehley solo?

I don’t know. I just saw a video of KISS doing “New York Groove.”

Well, I don’t know if you went through this, but when I got into punk rock, I got rid of all the records I was listening to before that.

I didn’t listen to my old records anymore, but I didn’t get rid of them. I still had Chuck Berry’s “My Ding-a-Ling” and Sabbath with the purple album cover.

Master of Reality. I couldn’t afford new records, so I sold off a bunch of old records. Then I went back and bought some of them again because I was getting back into that stuff. For the most part, the music that I was listening to before I got into punk rock, didn’t seem to hold up as much at the pre-punk that I was unfamiliar with like Alice Cooper and Black Sabbath. After getting into punk rock, Ted Nugent and KISS sounded a little weak to me. Then you compare Nugent to the MC5’s or the Stooges and it’s like, “Hack.”

Steve Jones told me, “I used to love Boston when I was a Sex Pistol.” I was like, “You’re funny.” Boston? Yeah. He loved Boston. The dichotomy of being a Sex Pistol and loving Boston was so funny.

Yeah. [Laughs]

It seems to me, when I realized a little bit about music and then going back and listening to Montrose and those kind of bands that I had to listen to, and I was like, “Wow. Those guys can really play their instruments.” They weren’t just a rock n’ roll hack band.

“Space Station #5.”

Exactly. The guitar on that was amazing.

Didn’t Ronnie Montrose, go on to make jazz fusion records?

Probably. It just seemed like the caliber of musicianship was so hardcore, and if it kept on going that way, without punk rock, I would have never gotten into playing music.

That’s totally the thing. I grew up with this whole idea of classical musicianship. What was considered good music, before I heard punk rock, was all about technique. It was like, “Oh, man, the drummer in Rush is one of the best drummers.” All these guys were really fucking playing. It seemed like a Catch 22 to me. It seemed impossible, at the late age of 16, to be in a rock band because I didn’t start playing guitar at age nine.

It seemed totally out of reach. It was like, “There is no way that I can just start playing now and become good like these guys that I admire as musicians and songwriters. That’s why I think punk rock is the best thing that ever happened to music.

Oh, for sure.

Some people say that punk rock is noise, but punk rock was an opening door to these realizations.

Listen to the first Damned record. The idea, at the time, was that punks can’t play and that is bullshit. There is some amazing playing on that record.

Right. Brian James was incredible.

It was so far above and beyond anything. It’s just different.

Exactly. It was just stripped down. It freaked me out. It was such a turn-on.

There was the criticism that punk bands only played three chords, but it’s like, “Yeah, but they played really good chords.” It’s getting to the heart of the matter. You don’t need all the frilly shit that surrounds an Emerson Lake and Palmer song.

“We all came from the exact same punk scene together, so it was really exciting. Soundgarden was doing really well. Nirvana started happening. Mother Love Bone kind of stalled out and that was kind of a bum deal, but Pearl Jam started up and that was awesome, so they were doing great again.”

For me, I was watching Steve Howe from Yes, and I was like, “There is no way I’m going to learn how to play like that guy in the next three years. This is boring. Let’s go chase some chicks.” The discovery for me was the Ramones and Mink Deville. Those guys were really good players. I was like this is really cool. It was just hopped up ‘50s basic rock n’ roll. I still get excited thinking back about listening to that music for the first time. Punk rock separated you from all the normal people, which is great as a teenager. It’s like, “I’m different from you.” Actually, it was like, “You suck and I actually have an idea of what’s really going on right now.”

Yeah. People justify wherever they’re at no matter what. I’m sure there were a lot of people that were like, “You’re just a fuckin’ weirdo.”

I was proud to be a weirdo.

Yeah. Just don’t beat me up.

[Laughs] Okay, let’s go back. Green River has broken up and you’re puking in excitement that the band has disbanded. You talk to Turner and you’re going to start a new project. Is this Mudhoney?

Yeah. After Steve quit Green River, he’d started playing with the Thrown Ups, the band that I talked about earlier that sort of made up song titles and songs on the spot. I was not a very good drummer, but I could keep a beat. It goes back to that earlier idea that Flipper crystalized in my mind that as long as you had a good beat, you could kind of make up whatever else around it. The Thrown Ups had this drummer who was a much better drummer than I am, but he was easily bored and he would start playing something and everyone would lock in and then he would just switch and start playing something else and lose everyone. I was like, “I can drum with you guys and we’ll at least know where we are.” So that’s how I weaseled into that band. I kept playing with Steve while I was in Green River and we always stayed in touch and were hanging out.

So he left to go to school because maybe there wasn’t a way to make a living playing rock n’ roll?

Maybe there wasn’t. We didn’t even believe that was possible. If you come up through hardcore, it’s different. I don’t know how it is for some bands, but you sometimes hear these musicians say they got into a band to get pussy. I was in a hardcore band and it was just dudes. There was no glamour or anything. No one was saying, “Dude, you’re really cool because you play in a hardcore band.” It was just a way to get your fuckin’ rocks off. The music was an end in itself. It wasn’t a way to get something else.

You were into it because of the music.

Yeah.

I never understood the terms of being in a band to get chicks, even though it happens.

Yeah. It did not happen in Mr. Epp.

Mr. Epp wasn’t a pussy band?

[Laughs] No.

I was always confused by people that said they just played in a band to get chicks. I was like, “Really? You don’t like playing? You’re just doing this so you can maybe meet a chick?” That was odd to me.

I can see that with someone in the mid ‘60s who saw the phenomenon of the Beatles and the Stones and girls just screaming and them thinking, “Hey, I want to get some of that kind of action.”

Yeah. So in ‘87, Green River disbands and Mudhoney begins.

Yeah. In late ‘87, Mudhoney started practicing and playing without Matt. The first practice we had with Matt was on New Years Day 1988. He was still living out in Aberdeen, which is about two hours away. He kept living out there for over a year and he would drive into town. He was the only one of us with a car, so he would have to go to all our apartments and pick us up to take us to practice. He would drive for two hours to Seattle and then pick each of us up and then he’d drive us to band practice and then drop everybody off and drive back home.

Wow. That’s commitment.

He never actually said he was in the band too. He just kept showing up.

[Laughs] Oh really? I love that. He was committed, but just not committing to the band.

Yeah. He didn’t acknowledge it until he quit in 1998 or ‘99, whenever it was. He was like, “Okay, I can’t do this anymore.”

So you guys start playing and you got a set together. You must have been itching to play it out live.

Yeah. I was working at Muzak and a bunch of musicians were working there. We weren’t making the music for Muzak. We were just duplicating tapes and shit like that.

Tell me what Muzak was exactly.

It was a company that provided background music for stores. It was what was called elevator music. They would have Nelson Riddle’s Orchestra do versions of Beatles songs. By this point, they were bought out by a company called Yesco here in Seattle and their whole thing was foreground music instead of background music, so they would actually put hit songs on these tapes. They provided music for Nordstrom’s and Ann Taylor stores. Some accounts had total background music and some accounts wanted pop hits of the day.

“You could turn up the gain on that thing and it would feedback like crazy, but i felt like I was Jimi Hendrix on live records in the parts between songs when the feedback is just going crazy.”

What were you doing at Muzak?

The total entry-level position was cleaning the tape cartridges. They looked like 8-track cassettes, except bigger. It was a proprietary format. The manager had come up with a recycling program to save money, instead of buying new cartridges for $4 every time. We’d clean off the returned cartridges and try to recycle the parts that weren’t broken. We had little sanders, but instead of sandpaper, we had this Brillo pad stuff and we’d spray this chemical that we called Spooge on the top to clean it off. It was really noisy and really dirty. I probably lost most of my hearing in that room. We would also play music, so the music had to be louder than the sanders.

You were just blasting your ears. Did you learn anything sonically from having to do all that work?

No. It was a dumb job where I could let my mind wander and think about lyrics or musical ideas or whatever. It was perfect, at that time, for what I needed. Bruce Pavitt worked there and I remember bringing in a tape that we had recorded on a boombox at practice. I played the first Mudhoney songs for Bruce at work and it just sounded like noise. The place was so loud and the tape was so loud that he was like, “I can’t tell what this is.” He knew me and Steve very well and he was a fan of the Melvins, so he knew Dan was a great drummer. He was like, “I trust your instincts.” He gave us some money to go and record some songs at Reciprocal with Jack Endino and that’s where the first single came from. As a band, we were very lucky. We were in a place where all these things kind of aligned. We knew a guy who had a record label and he trusted our judgment. We didn’t have to scrounge up money to record. It was probably $250 or something. It wasn’t a lot of money, but none of us had it.

What was happening in the Seattle scene with all the friends you were playing with in all the bands that were playing there?

In the group of people that I was hanging around in ‘85, if you were still playing straight up hardcore, you were kind of a numb nut. There were a bunch of newer bands like the Butthole Surfers, the Minutemen, Meat Puppets and Sonic Youth that came up through and around hardcore and they were going off in all different directions and making really creative music. I mean, what’s the point of trying to ape Minor Threat? Even Black Flag, very early on, stopped playing super fast and had more of a Sabbath influence. I loved going to their shows in that era. The audience reaction was just phenomenal to me. Half of the crowd would be totally into it and half of the crowd would be so pissed off and flipping them off until they played “Nervous Breakdown” or something. Then they would go crazy. Then they’d play “Nothing Left Inside” and they’d be flipping them off and going, “Fuck you!” It’s amazing how easily offended punk rock people were. It’s like, “You grew your hair! Fuck you!”

[Laughs] Right. They were holding on.

Yeah. I went to the University of Washington with Kim Thayil. We took at Philosophy class together, but I met hin at a T.S.O.L. show. He came up to me and said, “Hey, you’re in my class.” He had long hair and a mustache. It was like, “Dude, this hippy is talking to me.” [Laughs] We became really good friends and people were just starting to play in bands and slowing shit down a bit. I think the first band to put the brakes on were the Melvins, who were initially the fastest band in the Northwest and then they started going really slow and really heavy. I was like, “Fuck. This sounds amazing.”

Oh, right? What types of influences were happening to you at that time with Mudhoney?

We were going back to the basics. I was also a huge fan of the Wipers, who were a great band. I had been listening to a lot of Australian stuff like Feedtime and the Scientists, Lubricated Goat, and the Beasts of Bourbon.

Wow. Not many people know of the Beasts of Bourbon.

They were fantastic.

I was like, “What is this band?” I was listening to that band when I lived in S.F.

There was the Celibate Rifles and Cosmic Psychos. There was a great crop of bands from Australia that released killer records in the mid ‘80s. We always felt like we had one foot in hardcore, but we didn’t want to just ape anybody. That was our point of view. Using that as a filter, we were looking out and finding other things to be inspired by.

What happened with the first single? Did it get some play?

I don’t know. I think it must have gotten some. Initially, I think they pressed 1,000 on colored vinyl and 200 on black vinyl. The idea was that if you sent black vinyl to radio stations, it was less likely to be ripped off. It wasn’t so much of a collector thing. The initial 200 on black vinyl are now worth way more than the colored vinyl, which is kind of funny. I think it got play because we were able to go out on tour. We went on our first U.S. tour and Superfuzz came out right before or halfway through the tour. We did a leg on our own tour from Seattle to the East Coast and back and then met up with Sonic Youth in Seattle and went down the West Coast with them. We went down to L.A. and then over to Texas.

Were you proud of this music you were making with Mudhoney?

Oh yeah. We were very excited by it. I think Steve and I both felt like we were in a really great place. I don’t know if we were proud of it like chest-thumping, like we were the greatest thing ever, but it felt right.

That’s what I mean. You were proud of it and you could stand behind it.

Yeah. It felt to me like a lot more of what I was listening to and where I was coming from. It was just more comfortable to me than the later period Green River stuff.

When you went on tour, did you fund your own tour by just playing the shows?

Yeah.

You didn’t have record support did you?

No. What we did have is that Sub Pop bought a van. It was, ostensibly, the label van that any band that was on tour could use, but we probably used it more than anyone else, at that time. That was tour support, but we weren’t getting any money or anything. When we were asked to play with Sonic Youth, they asked us, “How much do you need per show?” I said, “$100 a night.” They were like, “You know what? We’ll give you $200.” We were like, “Holy shit!”

Wow. That is insane. What did you parents think of it now that you were out touring?

They were always sort of confused by it, like, “We don’t know what it is you’re doing.” I know they were secretly proud. Once we got to Europe and played Germany for the first time, my mom was like, “Oh, this is not just like you’re wasting your time here in Seattle not getting a real job.”

You’re actually traveling and seeing the world through music, which is a beautiful thing in its own right. When did it start to hit for you where you were actually going to be able to pay bills?

I don’t know if we thought that would happen. It wasn’t like I thought we were going to go on. I would just ditch my apartment and find a place to live when I got back. In ‘89, we went on this 9-week tour of Europe, the first part of which was in the U.K. with Sonic Youth. At that time, if you had Sonic Youth’s blessing in the U.K., you were golden. Dinosaur Jr. went with them the year before and they blew up over there, which reflected back over here. We went over there and got written about in the weekly papers like the Melody Maker, Sounds and NME and stuff like that. All of a sudden, the writer at the Seattle Times started writing about us. At the time, he was a notorious hack. He wrote concert reviews without ever showing up. I think there was a Jeff Beck concert that ended up being cancelled, but he wrote a review of how great it was and it got published even though Jeff Beck got sick at the last minute and didn’t show up. This guy wasn’t savvy enough to sniff out what was going on in his own hometown until it was written about in the U.K.

Then he came in on it.

Yeah. He kind of had to because kids were showing up and things were kind of bubbling up for us. Then a bunch of bands like Mother Love Bone got signed to a major label. Alice in Chains put out a record and they were the first band out of Seattle to have a gold record in late ‘90 or early ‘91, coming out of Seattle. Okay, Queensryche had huge records before that, but they were from a whole different scene.

“When we were asked to play with Sonic Youth, they asked us, “How much do you need per show?” I said, “$100 a night.” They were like, “You know what? We’ll give you $200.” We were like, “Holy shit!”

The focus was on the whole Seattle scene, so you guys were at the right place at the right time again.

Yeah. It was weird. We had been playing in bands off and on for 10 years and no one paid attention.

How was that to deal with?

There was a weird phenomenon in the ‘80s at local punk shows. At the most, 200 or 250 people would show up, even for touring bands, except for the Dead Kennedys and Black Flag. Then, suddenly, there were 1,200 punks in Seattle. We were like, “Where are these extra 1,000 people coming from?” They wouldn’t show up again until the next Dead Kennedys or Black Flag show. It was a total head scratcher. After our tour in Europe, Bruce and Jonathan had this idea to book a show at the Moore Theatre, which seats like 1,200. I thought they were fuckin’ nuts. I was like, “You’re putting us, who are barely known, and Tad and Nirvana, who were unknown, at this point, in the Moore Theatre. I said, “You’re going to lose your shirt.” And that show sold out.

How was it playing to a sold out theatre?

It was great.

It had to be a personal victory. You were selling this place out.

Right. The weird thing was that we weren’t around that much in the early ‘90s because we’d tour a fair amount. After that first 9-week European tour, we were like, “We are never going to do that again.” We’d do short bursts and go to some shows and be like, “Where are all the people that used to go to local shows?” Most of the original 200 people got put off by all the frat boys and jocks that were coming to the shows now and they were like, “This music doesn’t speak to me anymore.” If you’re in a band, you can’t complain that more people are coming to see you. That’s just shooting yourself in the foot.

True. To get some kind of recognition to where you’re selling out a 1,200 seat venue, it’s a subconscious victory. Not in an egotistical way. Just in a hard working, I put in a lot of time, way. You’re just doing it because you love it so much and then, all of a sudden, it happens. That must have been great.

Yeah. I felt vindicated from a musical perspective because I also DJed at the local college radio station in the mid ‘80s and I played the stuff that I loved. Most of the people were really into the British stuff like the Smiths and the Cure and way lesser bands that you might not even remember like the Mighty Lemon Drops. It was all so wimpy and mopey and it didn’t rock at all. I would play Poison 13 and Red Kross and the Wipers and the Birthday Party. I actually got admonished for playing the Birthday Party in the middle of the day because the hope of the general manager was that stores would play this radio station in the middle of the day and he didn’t want to bum out the people who were shopping. I was like, ‘Fuck you, man. I’m doing this for free. I’m going to play what I want.”

Right. So you get back to Seattle and you’re doing small jaunts all over the place. What happens when everything starts to explode up there? It was a huge phenomenon. The grunge scene just exploded and it was a huge movement. I was like, “Whoa. What is this?”

What happened was that people who had been fed on MTV and the radio and stuff were clearly looking for some sort of authenticity and they weren’t getting it in the C&C Music Factory and they weren’t getting it from Poison. I think actually Guns N’ Roses was kind of a bridge band between Poison and Nirvana. They were part of that L.A. glam scene, but they were a little grittier.

They were a little bit more rock n’ roll.

Yeah. They kind of paved the way a little bit for a band like Nirvana. It’s kind of funny to me that there was a big feud between the Nirvana and Guns N’ Roses camp. It all seemed so goofy to me. Guns N’ Roses had Duff McKagen who was from Seattle and he was involved in Seattle punk way before Kurt Cobain was.

Well, the whole focus seemed to be on the scene in Seattle and that’s that. This is what is happening. You guys were part of that whole scene and you were responsible for it, from what I’ve heard.

Luckily, for us, I think we kind of escaped the intense focus that some of the other bands received, so we could still go about our daily business without really getting hassled. We kind of had ringside seats to the whole thing. It was happening to friends of ours who we were friends with before all this shit happened.

What happened with Mudhoney through the whole thing?

I think by virtue of the fact that we were part of it, our records started selling more. We released Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge and we went on this U.S. tour and Nirvana released Nevermind and went on a U.S. tour and we were going to hook up with them in Portland and Seattle at the end of the tour. When we left a month earlier, the idea was that we would co-headline, and one band would headline in Portland and the other band would headline in Seattle. By the time the tour got back to the Northwest, it was clear that Nirvana was headlining both nights. Their record had just turned gold. I think that caught them off guard.

Did any of you guys think that would happen?

No. Not to that degree. I remember meeting up for a couple of shows with the Fluid in Europe and we both had advance copies of Bleach, the first Nirvana record. I think both of our bands were pretty blown away by it. We were like, “In a perfect world. these songs should totally be on the radio. This could be a hit record.” It didn’t happen for that record, but it happened for the next one. We didn’t think that was even a possibility. There was a party at Dan Peters’ house and Krist came in with the just finished mixes of Nevermind and played that. Van Conner from the Screaming Trees was like, “Holy shit. You guys are going to sell 100,000 records!” That was an insane amount of records in our world. That was as big as you could possibly be and play music like we play. I think it caught everyone by surprise.

That must have been insane. So then what did you guys do?

We kept touring and putting out records and stuff.

It seems like you guys just love to play and if you can keep playing and doing what you love, outside of society, that’s success.

For sure. I was 26 when Mudhoney started, so I wasn’t some easily swayed 19-year-old kid. I had a full grasp of the history of the bands that I loved and was into and how successful or unsuccessful most of them were. If you looked at my record collection at the time, 90% of it was made up of bands that people in the music biz would consider failures because they didn’t sell a huge amount of records. To me, they were successes because they made amazing records. Just a handful of them like, Alice Cooper, Black Sabbath, Creedence Clearwater and David Bowie had huge hits compared to the MC5, The Stooges or the New York Dolls or the Sonics or the bands that were happening in the ‘80s that we were into.

That’s the point that I was trying to convey. If you can keep doing what you love, that’s a successful thing.

I feel like we’re amazingly lucky people.

Luck does have a little bit to do with it, but it’s also perseverance, hard work and not giving up.

Yeah. We get to do what we want to do on our own terms. Generally, if we say we’d like to go to Brazil, we just contact a friend down there and go put on some shows.

After you gained some notoriety with Mudhoney, do you still get nervous before a show? I know I asked this earlier, but how about now?

Yeah. I get nervous before we play. It usually kind of subsides into the set, but beforehand, I’m just pacing around all over the place.

What is it that’s making you nervous? You’ve done it so much now.

I don’t know what the root of that feeling is. It could just be that I know my adrenaline is going to be kicking up a couple of notches and it’s that ‘fight or flight’ thing. I don’t know. It’s not like I’m nervous that I think we’re going to fuck shit up or forget our songs or anything. I guess it’s because I still fuckin’ care.

That’s a great thing. Do you have any favorite performances that stick out in your mind, that when you got done you were like, “Wow. That was pretty insane.”

Well, at this point, we have a 25-year history of playing shows, so it’s hard for me to recall. Some of the early shows just totally blur together. One of my favorite recent shows was in Sydney and we got to play with Feedtime. We were doing this traveling festival thing with a bunch of bands and we played a few shows on our own in clubs. To me, those shows are always way more fun than playing a festival, but not nearly as lucrative. We played with Feedtime, which is a band that Steve and I were listening to as Mudhoney was forming. They were a huge influence. By the time we got to Australia, in 1990, they had already broken up. We met the drummer, but we never thought we’d get to see them play, let alone play with them. That’s just the shit that has happened to me, more than it should have. I got to see and play with the Stooges and the Scientists and the Flesh Eaters. I did some touring with the remaining members of the MC5. It’s just stuff that shouldn’t be allowed to happen. It’s kind of a mind fuck. I never thought the Stooges would get back together again and that I would get to see them with Ron Asheton, and I got to play with them a couple of times.

I have to make a comparison to baseball here. If you’re a baseball player, you’re not going to get to play with Willie Mays, but in music, you do get to do that. It’s an extremely amazingly cool thing to have happen. You got to play on the same stage with the Stooges. That’s just a cool thing. Okay, so now what’s going on with Mudhoney?

We’re getting ready to go down to South America for five shows.

Imagine that. I can’t believe you’re going down there.

It’s crazy. we didn’t go down there until 2001, and this will be our seventh or eighth time now. The audiences down there are awesome. They are super passionate and super excited. The people down there are phenomenal.

Where in South America do you get to go?

We’re playing Chile, Argentina and Brazil.

Unreal. What’s it like coming out on stage as a person that played in Mr. Epp and now going and playing in South America?

My approach is very different. I’m not playing at people and trying to drive them away. [Laughs] At this point, there is no victory in that.

[Laughs] Right. No victory in emptying the place, so the strategy has changed slightly?

Yeah. [Laughs] Our point of view remains the same though. We do what we want. We’re not going to write songs based on what we think people might want to hear. We don’t care if you don’t like it, but if you do like it, we’re happy to have you along.

So you’re not looking to take prisoners. You’re just looking to do what you love.

Yeah. We don’t have any place to put prisoners.

[Laughs] There’s not a Mudhoney Guantanamo Bay. Do you have future plans to record a new record?

There’s nothing solid. We haven’t even started the process of writing new songs really. I imagine it will happen this year. The way we work, we have jobs and families and stuff, and Guy, our bass player, has the most real job of any of us. After this South America trip, he will have depleted his vacation time for about a year. Last year was really busy for us. In January, we went to Australia for three weeks and we were only going to be gone for ten days. I think Guy was having a little bit of stress at work.

Did you ever think when you were doing this that it was ever going to turn out like this fairytale?

I don’t know if it’s a fairytale exactly, but I never thought that we would last as long as we have. When we started out, we thought it might last three years tops because that’s how long the last band lasted.

Do you work a regular job?

Yeah. Luckily, it’s at Sub Pop, so I have a lot of leeway. It’s not a job that takes a lot of skill. It just takes a lot of my attention. I manage the warehouse and I ship stuff to stores and distributors. I have a couple of people that know the job well enough to fill in for me when I’m gone.

Okay. One last question.

Wait. We haven’t even talked about surfing.

[Laughs] Well, I’m not completely done yet. How did you get into surfing up in the Pacific Northwest?

For some reason, when my parents moved up here, they looked around the area and were like, “What’s an activity that our kid can do besides piano lessons?” Boeing had this Friday night ski school, so when I was six, my dad would drive 45 minutes up to the mountain to take me to the beginner hill and I would take classes. After one season of that, he was like, “I’m not just going to sit in the lodge. I’m going to start taking lessons too.” Early on, I had this love of just moving and gliding. When skateboarding came along, I was like, “This is something I can do in the summertime.” I’d always watch Wide World of Sports and, occasionally, they’d have surfing on there. I was like, “That’s the third thing. That would make the other stuff that I’m into complete.” I never thought that you could surf up here. I was aware of people that were surfing here, but I just thought they were fucking nuts. Some of my friends were doing it and I just thought they were crazy. I mean, the water here can kill you if you’re just swimming without a wetsuit. It’s so cold that it will kill you in 20 minutes or something. My wife and I started scuba diving and, despite the fact that it was super cold, it was kind of doable around here.

The development of wetsuits definitely helped.

For sure. We had talked about learning to surf and my wife was like, “Okay, you can’t start yet. I need to get a jump start on this.” She didn’t have the skiing or skateboarding background, although we did snowboard together a lot, so she went down to San Diego and went to Surf Diva camp a couple of times and learned the basics. One time we used frequent flyer miles and went to a surf camp in Brazil. We did that ten years ago and then didn’t go again for another year, when we went to another surf camp. I realized that every time I did it, I was almost starting from scratch, so if I wanted it to be more enjoyable, I had to do it on a more regular basis. A friend of mine runs the Snowboard Connection and they also sell surf gear. He loaned us a couple of wetsuits and we went out to Westport. It was one of those classic coastal Washington days. Everything is just gray and there might have been a drizzle and we were looking at each other like, “This is going to be fucking horrible.” We put on the wetsuits and went out there anyway and had a great time. That made us get our own boards and our own wetsuits and start doing it. Then three years ago, we both got winter wetsuits and we have been going year-round ever since. The crazy thing is that I think about surfing way too much. It would probably be the same way if it were something that I grew up doing as a kid, but it’s almost like I’m back in eighth grade algebra class reading Skateboarder magazine in the cover of my math textbook and not paying attention and flunking out of class. I guess the word is stoke, right?

[Laughs] Yes. It sounds as if you’re pretty stoked. Look, the love of surfing is such an amazing thing. I dream of going every day and I’ve been surfing since I was nine years old and I’m 52 now. That’s 43 years of still having that love of it. I don’t know. It’s a very cool thing, so it’s not that weird for you to experience this love of surfing. How is it when you hit the water in Westport? What does that do for you as a person?

Much like before I play a show, I get nervous. [Laughs] Once you’re wading out into the water, that dissipates. Westport is this beach break and if the waves have any power to them, it’s pretty hard to get out sometimes. There is a rip along the jetty, but that is also super hairy because you could get a wave that pushes you into the rocks.

The rocks are so much scarier than they actually are.

Yeah. Probably. The line up closest to the jetty is the hot shots. It’s a beach break, so there’s shit going on for miles. We usually paddle over a peak or two and sit there.

Do you have the waves to yourself?

Not at Westport, but there are places around here that you can.

What’s crowded at Westport?

In the summertime, there might be 20 people around a peak, so there are about 80 people outside on those days. That’s the extreme. It wasn’t that crowded when I went out last December and it was 28 degrees in the air. [Laughs]

If it was raining, it would have been snowing. How cold is the water?

It ranges in the wintertime in the high 40s. Last summer, it was 63 degrees at times. It’s just like Ventura in the winter. In the summer, you can go out with no booties and gloves and no hood.

We could almost trunk it in 63 degrees.

Well, I saw a dude go out last summer in trunks and he didn’t last very long.

Oh no?

No. It was on a super hot day.

How do you compare surfing to performing or playing music?

I don’t know. They are totally different feelings. They are both ends in and of themselves. The joy I get out of playing music, that’s what it’s all about. The joy I get out of surfing, that’s what it’s all about. Clearly, there is no way I’m going to get on the world tour or anything like that. So there is no thought that it’s going to take me to another place. It’s all about the thing you’re doing. It’s an end in itself.

It’s really interesting for me to hear your stories. This was totally good.

Awesome, Steve. Hopefully, we’ll run into next time we play down there.

Definitely, If we’re somewhere we can go surfing, we will definitely go surfing.

I’m going to San Clemente the first week of June, if you don’t mind hanging out with a kook.

Bring it. It’s all about surfing. It’s totally fun.

Do you mainly surf a shortboard now?

I have different boards. My brother has been making me surfboards for a long long time, but I have this one board which is my old throwback from the early ‘70s. The shape is based on the Pig that Dewey Weber made.

How big is it?

It’s 7’2”. It’s a little thicker, so the paddling is much faster and easier. I have a 6’3” and I have a 6’2” and longboards. I grew up longboarding as a kid. Our first boards, one guy would carry the nose and one guy would carry the tail because it was so heavy. It was funny. Growing up surfing was insane.

Where did you grow up surfing?

I was surfing in Huntington Beach and Seal Beach. I lived a little inland from Seal Beach. There was a riverbed that ran all the way to the ocean, so we could get on our bicycles and ride down three or four miles to the beach.

It’s like those L.A. riverbeds that are concrete.

Exactly. Two of them ran down into one at Long Beach and filtered into this power plant. The waves were amazing. As a kid, you’re just so stoked to be in the water. I was a swimmer in Seattle, in Kenmore, so I was totally into racing and all that.

You were from up here?

No. When Boeing was happening in the early ‘70s, we were up there for a while, and I have relatives up there. My aunt lives in Bellevue and I saw her when were up there for the EMP thing. I lived up there in third grade. How old are you in third grade? It was probably the late ‘60s.

When were you born?

‘61.

I was born in ‘62.

The transition of learning how to surf when we moved back down, was cool. We were lucky enough to have parents who would drive us to the beach. I was lucky to have an older brother, too. Once he got his license, we would just surf so much. It just happened to be where we were living at the time.

Was there ever a time when you didn’t surf at all?

No. I always surfed. There was a time in punk rock when it wasn’t cool to be a surfer though.

I kind of felt that way, but that didn’t happen with Mudhoney.

Even with skateboarding, it was the same. It was like, “Look at all these idiots here. They don’t even understand.” We still surfed and skated though. It’s in your blood, but you didn’t carry your skateboard to a gig. No one really cared if you were skateboarder or not back then. It was like, “Here’s a group of young kids and they don’t really belong here.”

There was a group of kids here that would carry their skateboards to gigs and, basically, use them as weapons. You never saw them ride their boards. They just carried them around.

In case of an outbreak. I love surfing. That’s the one thing you can do the rest of your life. There are 80-year olds in Malibu who are still paddling into waves and riding them and and enjoying it.

Yeah. Unfortunately, the one thing with skateboarding is that it hurts as you get older.

It hurts, but you can still just roll. Slamming on concrete hurts, but it’s cool. You can figure out how to take the slam a little better even though it hurts more. I don’t know. I can’t even bend my knee right now. It happens, but there’s a really good session tomorrow, which will be good. Down here, a lot of dudes are making backyard pools that are built to skate. It’s happening a lot. These are really good pools. I’m almost 53 and it’s still cool to be able to grind the coping. Right. Right. Hopefully, you’ll remember to call me when you come down. Hit me up when you come down this way. Jay Adams lives down in San Clemente, so I’ll call him and we’ll all go surfing.

That sounds great.

The waves are coming in today and tomorrow down here.

It’s windy up here.

When is the best time to surf up there?

Generally, it’s the spring and fall. In the winter, the Strait of Juan de Fuca is a little more protected from the wind and the giant swells kind of dissipate as they come down the Strait. There might be 20 to 30-foot waves on the coast, but it will translate into shoulder high waves down the Strait.

That’s always comforting. “It’s 30-feet. Let’s go out.” I don’t know about that one. Okay, Mark, have a great day and thank you so much. This was totally great.

Sure. This was awesome. Thank you.

INTERVIEW WITH STEVE TURNER

Steve?

Olson.

Hi, Steve.

How’s it going?

Super good. How are you?

Pretty good.

What’s going on? [Laughs]

I was sitting in the backyard. It’s actually nice out right now.

Oh it is? Yeah, it’s beautiful down here as well.

Killer.

Super killer. [Laughs] You’re funny. Did you graduate from the University of Washington?

No. Mark did. I never got a degree.

My dad graduated from the University of Washington.

Oh yeah? Mark went there. Most of my friends went there, but I never did. I went to Western Washington University in Bellingham for a year.

Cool. What’s your name?

[Laughs] My name is Steve Turner.

Any relationship to Turner Skateboards?

Not at all. I’ve never even heard of Turner Skateboards, but it’s a good name for a skateboard company.

Well, yeah. That’s a bit biased, but they made amazing skateboards. You don’t know the Turner SummerSki? They were so futuristic and they still are futuristic.

What era was this?

It was the mid 70’s. You would love them.

I want one now. [Laughs]

You should have one. Okay, where did you grow up, Steve?

I grew up in Seattle in a place called Mercer Island.

When did you get turned on to music?

Well, the easy answer is I got into skateboarding and punk rock, but when I was younger, I really liked the Clancy Brothers, the Irish group. I really liked Irish music because my dad had some of that around the house. He had a Lead Belly 10-inch with “Goodnight Irene” on it that I thought was really cool. My brother had ordered a best of ‘60s rock record from K-Tel. It was a three-album box-set that I thought had some stuff that was pretty good. I really liked “Pushin’ Too Hard” by the Seeds. I didn’t really get into rock music too much until I was a teenager and I got into skateboarding. Because of you, and people like you, we started listening to Devo and The Clash instead of Ted Nugent.

It was a transitional period in music and skateboarding.

I feel like it happened literally overnight at my friend’s ramp. I liked it. I thought, “This stuff sounds pretty cool to me.”

I totally agree with you and I back your decision.

Totally. [Laughs]

Was your brother older?

My brother was five years older than me.

Was there was a small influence by the older brother?

Maybe there was, just a little bit. I mean, he really wasn’t into rock music. Someone may have given him that K-Tel set. He liked Barbra Streisand, Liza Minnelli and Broadway show-tunes, which wasn’t much of an influence on me. [Laughs]

Well, that’s interesting. What kind of stuff did you do as a kid? I’m looking for how influences happened, after the fact.

Well, by the time I was six years old, I was really into riding my bike. I had a Stingray. I was really into bicycles and I liked playing soccer. I liked skiing and building tree forts. Our neighborhood was near some woods, so we were always building tree forts and stuff.

You know, we built tree forts when I lived up there in Kenmore for a little amount of time. We built tree forts and went skiing. My older brother built an F Troop tower, like a lookout tower, that stood maybe two floors up, and he convinced me to go up there to tell him what the vantage point was like and then he pushed it over.

[Laughs] My brother wouldn’t have done that to me. He was nice.

My brother was nice, but he was also vindictive, occasionally. Well, I was his brother, so I was just annoying I’m sure. Remember when they had those extension chopper forks for Stingray’s where you just bolt them on to the front forks?

Yeah.

It really wasn’t the safest design. My brother had pushed me over in the tree fort and then he had built a jump and he put the chopper forks on and he went off the jump and, as he was in mid air, his front tire became disconnected, so he landed on his forks and got a little bit of payback.

[Laughs] Yeah.

So you’re into Stingray’s, soccer and skiing. Do you think there was a part of you that loved that sense of motion?

Definitely. I was bombing down hills on a Big Wheel as a little kid. Anything where there was a little bit of danger involved, I was all for it.

When did you first get turned onto skateboards?

It was early in 1975. My dad was an import/export businessman. Mostly, he did agricultural stuff, but he got into some sporting gear in the mid ‘70s and he brought home six really shitty Asian skateboards along with the second edition of Skateboarder Magazine. It was the one with the blonde kid, barefoot in a pool on the cover. He was like, “Skateboarding is a new thing in California. See if you like it.” Most of those skateboards were the worst because none of them had soft wheels or proper wheels yet. One of them had what seemed like glass wheels. It was unrideable. One had black rubber tires and that was one I rode. It was cool because I could leave skid-marks, just like I could on my bike. That’s a good design, right? I still think kids would buy a skateboard that left marks. [Laughs]

“In Seattle, people didn’t really know what punk rock was so much. I just remember seeing this hippy guy with a beard and long hair. He was dressed up crazy like a punk rocker and he had a toilet seat around his neck.”

Oh, for sure. [Laughs]