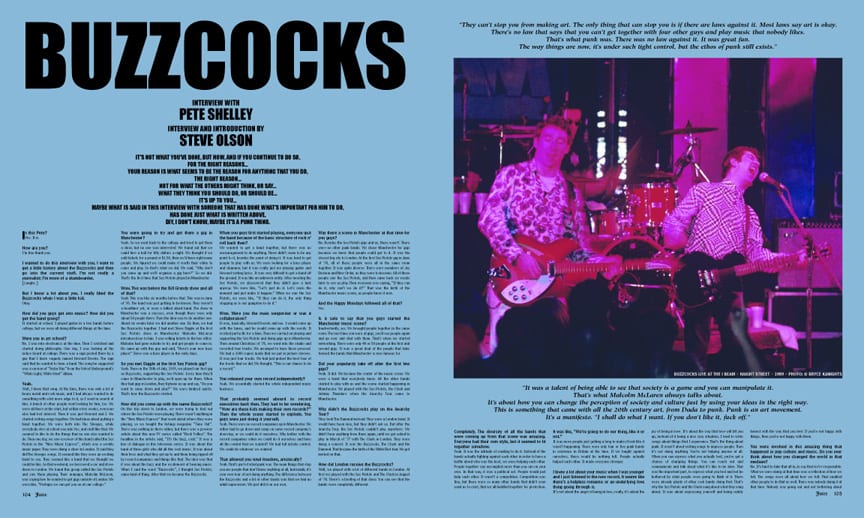

INTERVIEW WITH PETE SHELLEY

INTERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION BY STEVE OLSON

PHOTOS COURTESY OF BRYCE KANIGHTS

It’s not what you’ve done, but how, and if you continue to do so, for the right reasons… Your reason is what seems to be the reason for anything that you do, the right reason… Not for what the others might think, or say… What they think you should do, or should be… It’s up to you… Maybe what is said in this interview with someone that has done what’s important for him to do, has done just what is written above, DIY, I don’t know, maybe it’s a PUNK thing.

“It was the attitude of wanting to do it. Instead of the bands actually fighting against each other in order to have a battle about who was the best, we were helping each other. People together can accomplish more than you can on your own. In that way, it was a political act. People would just help each other. It wasn’t a competition. Competition was fine, but there were so many other bands that didn’t even want us to exist, that we all huddled together for protection.”

Is this Pete?

Yes. It is.

How are you?

I’m fine thank you.

I wanted to do this interview with you. I want to get a little history about the Buzzcocks and then go into the current stuff. I’m not really a journalist; I’m more of a skateboarder.

[Laughs.]

But I know a lot about you. I really liked the Buzzcocks when I was a little kid.

Okay.

How did you guys get into music? How did you get the band going?

It started at school. I played guitar in a few bands before college, but we were all doing different things at the time.

Were you in art school?

No. I was into electronics at the time. Then I switched and started doing philosophy. One day, I was looking at the notice board at college. There was a sign posted there by a guy that I knew vaguely named Howard Devoto. The sign said that he wanted to form a band. The song he suggested was a version of “Sister Ray” from the Velvet Underground’s “White Light, White Heat” album.

Yeah.

Well, I knew that song. At the time, there was only a lot of heavy metal and rock music, and I had always wanted to do something with a bit more edge to it, so I went in search of him. A bunch of other people went looking for him, too. We were all there at the start, but within a few weeks, everyone else had lost interest. Then it was just Howard and I. We started writing songs together. We had ideas about putting a band together. We were both into The Stooges, while everybody else at school was into Yes, and stuff like that. We seemed to like to do the things that no one else wanted to do. Then one day, we saw a review of this band called the Sex Pistols in the “New Music Express”, which was a weekly music paper. They were doing a show in London. It said they did The Stooges songs. It seemed like they were an exciting band to see. They seemed like a band that we thought we could be like. So that weekend, we borrowed a car and drove down to London. We found this group called the Sex Pistols and saw them playing. Their manager, Malcolm McLaren, was saying how he wanted to get gigs outside of London. We were like, “Perhaps we can get you on at our college.”

You were going to try and get them a gig in Manchester?

Yeah. So we went back to the college and tried to get them a show, but no one was interested. We found out that we could hire a hall for fifty dollars a night. We thought if we sold tickets for a pound or $1.50, then we’d have right many people. We figured we could make it worth their while to come and play. So that’s what we did. We said, “Why don’t you come up and we’ll organize a gig here?” So we did. That’s the first time that Sex Pistols played in Manchester.

Wow. This was before the Bill Grundy show and all of that?

Yeah. This was like six months before that. This was in June of ’76. The band was just getting to be known. They weren’t a headliner yet, or even a talked about band. The show in Manchester was a success, even though there were only about 50 people there. Then the idea was to do another one. About six weeks later we did another one. By then, we had the Buzzcocks together. I had met Steve Diggle at the first Sex Pistols show in Manchester. Malcolm McLaren introduced me to him. I was selling tickets in the box office. Malcolm had gone outside to try and get people to come in. He came up with this guy and said, “Here’s your new bass player.” Steve was a bass player in the early days.

So you met Diggle at the first Sex Pistols gig?

Yeah. Then on the 20th of July, 1976, we played our first gig as Buzzcocks, supporting the Sex Pistols. Every time they’d come to Manchester to play, we’d open up for them. When they had gigs in London, they’d phone us up and say, “Do you want to come down and play?” We were kindred spirits. That’s how the Buzzcocks started.

How did you come up with the name Buzzcocks?

On this trip down to London, we were trying to find out where the Sex Pistols were playing. There wasn’t anything in the “New Music Express” that week about where they were playing, so we bought the listings magazine “Time Out”. There was nothing in there either, but there was a preview article about this new TV series called “Rock Follies”. The headline in the article said, “It’s the buzz, cock.” It was a line of dialogue in this television series. It was about this band of three girls who did all this rock music. It was about their lives and what they got up to and them being ripped off by record companies and things like that. The idea was that it was about the buzz and the excitement of hearing music. When I said the word “Buzzcocks”, I thought Sex Pistols, same kind of thing. After that we became the Buzzcocks.

When you guys first started playing, everyone quit the band because of the basic structure of rock n roll back then?

We wanted to get a band together, but there was no encouragement to do anything. There didn’t seem to be any point to it, besides the point of doing it. It was hard to get people to play with us. We were looking for a bass player and drummer, but it was really just me playing guitar and Howard writing lyrics. It was very difficult to get a band off the ground. It was like an unknown entity. After meeting the Sex Pistols, we discovered that they didn’t give a fuck anyway. We were like, “Let’s just do it. Let’s seize the moment and just make it happen.” When we saw the Sex Pistols, we were like, “If they can do it, the only thing stopping us is our gumption to do it.”

Wow. Were you the main songwriter or was it collaboration?

It was, basically, Howard Devoto and me. I would come up with the tunes, and he would come up with the words. It worked perfectly for a time. Then we carried on playing and supporting the Sex Pistols and doing gigs up in Manchester. Then around Christmas of ’76, we went into the studio and recorded four tracks. We arranged to have those pressed. We had a 1000 copies made that we put in picture sleeves. It was just four tracks. We had just picked the best four of the tracks that we did. We thought, “This is our chance to do a record.”

You released your own record independently?

Yeah. We essentially started the whole independent music business.

That probably seemed absurd to record executives back then. They had to be wondering, “How are these kids making their own records?” Then the whole scene started to explode. You guys were just doing it yourself.

Yeah. There were no record companies up in Manchester. We either had to go down and camp on some record company’s doorstep, or we could do it ourselves. Why bother with the record companies when we could do it ourselves and have all the control that we wanted? We had full artistic control. We could do whatever we wanted.

That allowed you total freedom, artistically?

Yeah. That’s part of what punk was. The main things that stop you are people that don’t know anything at all, but mainly it’s your own fear of not doing anything. The difference between the Buzzcocks and a lot of other bands was that we had no adult supervision. We just did it on our own.

Was there a scene in Manchester at that time for you guys?

No. Besides the Sex Pistols gigs and us, there wasn’t. There were no other punk bands. We chose Manchester for gigs because we knew that people could get to it. It was the closest big city to London. At the first Sex Pistols gig in June of ’76, all of these people were all in the same room together. It was quite diverse. There were members of Joy Division and New Order, as they were to become. All of these people saw the Sex Pistols, and then came back six weeks later to see us play. Then everyone was saying, “If they can do it, why can’t we do it?” That was the birth of the Manchester music scene, as people know it now.

And the Happy Mondays followed all of that?

Yes.

Is it safe to say that you guys started the Manchester music scene?

Inadvertently, yes. We brought people together in the same room. The next time you were at gigs, you’d see people again and go over and chat with them. That’s when we started networking. There were only 40 or 50 people at the first and second gigs. It was a great deal of the people that later formed the bands that Manchester is now famous for.

Did your popularity take off after the first few gigs?

Yeah. It did. We became the center of the music scene. We were a band that everybody knew. All the other bands started to play with us and the scene started happening in Manchester. We played with the Sex Pistols, the Clash and Johnny Thunders when the Anarchy Tour came to Manchester.

Why didn’t the Buzzcocks play on the Anarchy Tour?

They took The Damned instead. They were a London band. It would have been nice, but they didn’t ask us. But after the Anarchy Tour, the Sex Pistols couldn’t play anywhere. We didn’t hear anything from them again, until we got asked to play in March of ’77 with The Clash in London. They were doing a concert. It was the Buzzcocks, The Clash and the Damned. That became the birth of the White Riot tour. We got invited on that.

How did London receive the Buzzcocks?

Well, we played with a lot of different bands in London. At first we played with the Sex Pistols and The Clash in August of ’76. There’s a bootleg of that show. You can see that the bands were completely different.

Completely. The diversity of all the bands that were coming up from that scene was amazing. Everyone had their own style, but it seemed to fit together somehow.

Yeah. It was the attitude of wanting to do it. Instead of the bands actually fighting against each other in order to have a battle about who was the best, we were helping each other. People together can accomplish more than you can on your own. In that way, it was a political act. People would just help each other. It wasn’t a competition. Competition was fine, but there were so many other bands that didn’t even want us to exist, that we all huddled together for protection.

It was like, “We’re going to do our thing, like it or not.”

It was more people just getting along to make it look like it wasn’t happening. There were only four or five punk bands in existence in Britain at the time. If we fought against ourselves, there would be nothing left. People actually helped each other. It made everyone stronger.

I knew a lot about your music when I was younger and I just listened to the new record. It seems like there’s a helpless romantic or an underlying love thing going through it.

It’s not about the angst of being in love, really, it’s about the joy of being in love. It’s about the way that love will lift you up, instead of it being a nice cozy situation. I tend to write songs about things that I experience. That’s the thing about punk. It wasn;t about writing songs to impress people. Then it’s not doing anything. You’re not helping anyone at all. When you can express what you actually feel, you’ve got a chance of changing things. You can reach out and communicate and talk about what it’s like to be alive. That was the important part, to express what you feel and not be bothered by what people were going to think of it. There were already plenty of other rock bands doing that. That’s why the Sex Pistols and the Clash sang about what they sang about. It was about expressing yourself and being rudely honest with the way that you feel. If you’re not happy with things, then you’re not happy with them.

You were involved in this amazing thing that happened in pop culture and music. Do you ever think about how you changed the world in that medium?

No. It’s hard to take that all in, to say that we’re responsible. What we were doing at that time was a reflection of how we felt. The songs were all about how we felt. That enabled other people to do that as well. There was nobody doing it at that time. Nobody was going out and not bothering about whether they sold records. When we started punk, it was the most uncommercial form of music. We were expecting not to be liked. It was a big shock when people went, “Wow. This is fantastic.” We gave everybody a voice. You could go on stage and say, “Fuck.” It was word you used if you weren’t hiding away from anything. It was like, “I can do and say anything I want.” It encouraged people to become creative and form bands and do the things they wanted to make their own fun. It enabled people to become active participants in culture, rather than just being passive consumers. Within six months of playing with the Sex Pistols, you had hundreds and thousands of bands like that in Great Britain. One of the things about punk was that you didn’t even need to know how to play.

It seemed like you guys learned how to play pretty quick.

[Laughs.] Well, if you do something enough and practice it, you get better.

How was it dealing with the popularity? It seems like it happened pretty quickly for you.

It did. Compared to how things happen now, it was tremendously fast. We started from nothing and had a major record deal by the end of the year. We signed to a company called United Artists. We got signed on the same day that Elvis Presley died, Aug 16, 1977. The band was only going 13 months before we got a record deal. That was quick to get a record deal.

Were the major labels frightened of the new punk thing that was happening or did they want to jump on quickly?

They wanted to jump on quickly. The whole punk thing took everyone by surprise. There was music happening and the record companies didn’t have any of those bands in their catalogs. They were falling all over themselves to sign the Sex Pistols. The Sex Pistols made all their money by signing to record companies that were afraid to release their records. If you listen to the Sex Pistols records, they’re not really frightening are they?

No.

At the time, they were. They shook the foundations of what the record companies wanted, which was to be in control of the business. There was a popular demand for something that the record companies didn’t even know existed. That was generated by the fact that it had a ring of authenticity to it. It was the kind of music that people could have access to.

How was it for you to come to the United States for the first time?

Well, it was quite a while before we got to the States. We didn’t get over there until 1979. We had the album of singles. It was the first album for the band, even though it was just a collection of the singles that we’d released over the last two or three years. By ’79, we’d done eight singles. They were released as “Singles Going Steady”, along with the B-sides. That was our first compilation album, but it was first album to be released in the States. It allowed people to catch up. Then our last album right before we split up was the next release after that. It was called “A Different Kind of Tension”. We released that in ’79. By then, we were on our way out. By the time we came over to America, I was already dead, emotionally scarred by the way the band had been eaten up and absorbed by drugs.

How old were you when this was going down?

In ’76, I was 21. By the time I was in America, I was 24.

Did the American audience accept you immediately?

Yes. We had a great reception in America. We hit the East and the West Coast and a few cities across the top. I’m sure there were great places in the middle, but we didn’t get to go there. We didn’t get to choose where we played. It was never the bands decision about where to play or not to play. We played places like Boston, Chicago, Minneapolis, San Francisco and LA.

Do you think you’ll play the States again soon?

We’re thinking about doing part of the Warped Tour, so we should be over there sometime in June.

Do you make a living from only making music?

Yes.

That’s fucking brilliant.

Steve Diggle and I are conscientious objectors to work. Even if nothing happened, we’re still not going to work. We’d rather starve than having to get off work at the same time every day and do something for somebody else. I know that millions of people have to do it, but we were so stupid that we actually believed if you tried hard enough and believed in what you do, than it need never happen to you. Sometimes you have to put up with having no money, no friends and no hope, but I love playing music. Sometimes it’s even worse than a job.

Right.

The thing is that there’s no signing off and going, “It’s not my concern anymore.” It’s always something you feel passionate about.

So you’ll play music until you die?

I hope. After the final encore, that would be the best way to go. You’ve done a really good gig, you walk off, and you’re dead. It’s far better than dying in the gutter.

FOR THE REST OF THE STORY, ORDER ISSUE #60 BY CLICKING HERE…

SHARE THIS POST:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)