BONES BRIGADE CHRONICLES:

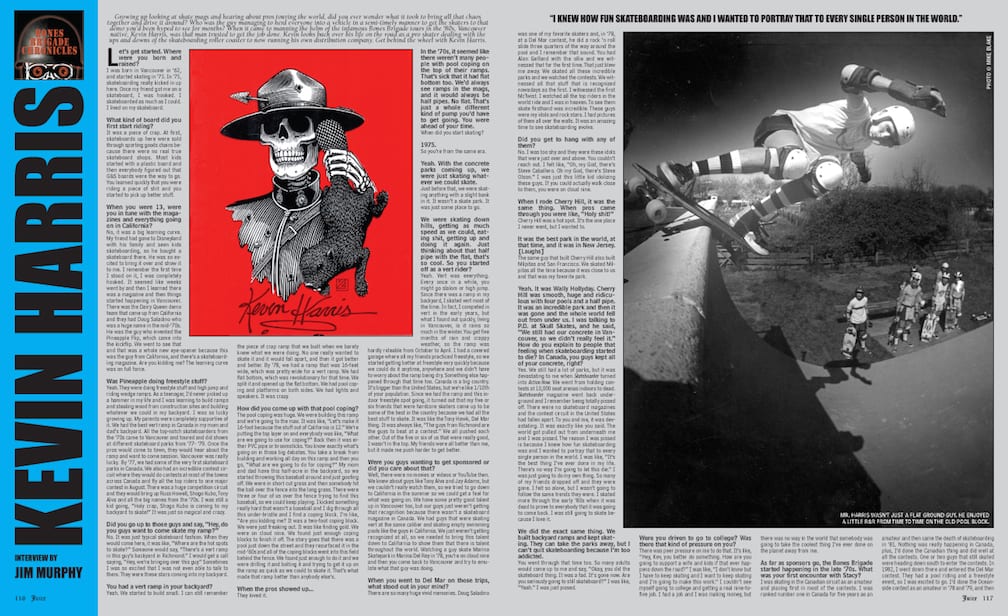

KEVIN HARRIS

INTERVIEW by JIM MURPHY

ARTWORK by VCJ

PHOTO by MIKE BLAKE

Growing up looking at skate mags and hearing about pros touring the world, did you ever wonder what it took to bring all that chaos together and drive it around? Who was the guy managing to herd everyone into a vehicle in a semi-timely manner to get the skaters to that demo you’d been hyped to see for months? When it came to manning the helm of the infamous Bones Brigade tours in the ‘80s, Vancouver native, Kevin Harris, was that man trusted to get the job done. Kevin looks back over his life on the road as a pro skater dealing with the ups and downs of the skateboarding roller coaster to now running his own distribution company. Get behind the wheel with Kevin Harris.

Let’s get started. Where were you born and raised?

I was born in Vancouver in ‘62, and started skating in ‘75. In ‘75, skateboarding really kicked in up here. Once my friend got me on a skateboard, I was hooked. I skateboarded as much as I could. I lived on my skateboard.

What kind of board did you first start riding?

It was a piece of crap. At first, skateboards up here were sold through sporting goods chains because there were no real true skateboard shops. Most kids started with a plastic board and then everybody figured out that G&S boards were the way to go. You learned quickly that you were riding a piece of shit and you started to pick up better stuff.

When you were 13, were you in tune with the magazines and everything going on in California?

No, it was a big learning curve. My friend had gone to Disneyland with his family and seen kids skateboarding, so he bought a skateboard there. He was so excited to bring it over and show it to me. I remember the first time I stood on it, I was completely hooked. It seemed like weeks went by and then I learned there was a magazine and then things started happening in Vancouver. There was the Dairy Queen demo team that came up from California and they had Doug Saladino who was a huge name in the mid-’70s. He was the guy who invented the Pineapple Flip, which came into the kickflip. We went to see that and that was a whole new eye-opener because this was the guy from California, and there’s a skateboarding magazine. Are you kidding me? The learning curve was on full force.

Was Pineapple doing freestyle stuff?

Yeah. They were doing freestyle stuff and high jump and riding wedge ramps. As a teenager, I’d never picked up a hammer in my life and I was learning to build ramps and stealing wood from construction sites and building whatever we could in my backyard. I was so lucky growing up. My parents were completely supportive of it. We had the best vert ramp in Canada in my mom and dad’s backyard. All the top-notch skateboarders from the ‘70s came to Vancouver and toured and did shows at different skateboard parks from ‘77- ‘79. Once the pros would come to town, they would hear about the ramp and want to come session. Vancouver was really lucky. By ‘77, we had some of the very first skateboard parks in Canada. We also had an incredible contest circuit where they would do contests at most of the towns across Canada and fly all the top riders to one major contest in August. There was a huge competition circuit and they would bring up Russ Howell, Shogo Kubo, Tony Alva and all the big names from the ‘70s. I was still a kid going, “Holy crap, Shogo Kubo is coming to my backyard to skate!” It was just so magical and crazy.

Did you go up to those guys and say, “Hey, do you guys want to come skate my ramp?”

No. It was just typical skateboard fashion. When they would come here, it was like, “Where are the hot spots to skate?” Someone would say, “There’s a vert ramp in this guy’s backyard in Richmond.” I would get a call saying, “Hey, we’re bringing over this guy.” Sometimes I was so excited that I was not even able to talk to them. They were these stars coming into my backyard.

You had a vert ramp in your backyard?

Yeah. We started to build small. I can still remember the piece of crap ramp that we built when we barely knew what we were doing. No one really wanted to skate it and it would fall apart, and then it got better and better. By ‘78, we had a ramp that was 16-feet wide, which was pretty wide for a vert ramp. We had flat bottom, which was revolutionary for that time. We split it and opened up the flat bottom. We had pool coping and platforms on both sides. We had lights and speakers. It was crazy.

How did you come up with that pool coping?

The pool coping was huge. We were building this ramp and we’re going to the max. It was like, “Let’s make it 16-foot because the stuff out of California is 12.” We’re putting the top layer on and everybody was like, “What are we going to use for coping?” Back then it was either PVC pipe or broomsticks. You know exactly what’s going on in those big debates. You take a break from building and working all day on this ramp and then you go, “What are we going to do for coping?” My mom and dad have this half-acre in the backyard, so we started throwing this baseball around and just goofing off. We were in short cut grass and then somebody hit the ball over the fence into the long grass. There were three or four of us over the fence trying to find this baseball, so we could keep playing. I kicked something really hard that wasn’t a baseball and I dig through all this under-bristle and I find a coping block. I’m like, “Are you kidding me? It was a two-foot coping block. We were just freaking out. It was like finding gold. We were on cloud nine. We found just enough coping blocks to finish it off. The story goes that there was a pool just down the street and they resurfaced it in the mid-’60s and all of the coping blocks went into this field behind the fence. We found just enough to do it and we were drilling it and bolting it and trying to get it up on the ramp as quick as we could to skate it. That’s what made that ramp better than anybody else’s.

When the pros showed up…

They loved it.

In the ‘70s, it seemed like there weren’t many people with pool coping on the top of their ramps. That’s sick that it had flat bottom too. We’d always see ramps in the mags, and it would always be half pipes. No flat. That’s just a whole different kind of pump you’d have to get going. You were ahead of your time.

When did you start skating?

1975.

So you’re from the same era.

Yeah. With the concrete parks coming up, we were just skating whatever we could skate.

Just before that, we were skating anything with a slight bank in it. It wasn’t a skate park. It was just some place to go.

We were skating down hills, getting as much speed as we could, eating shit, getting up and doing it again. Just thinking about that half pipe with the flat, that’s so cool. So you started off as a vert rider?

Yeah. Vert was everything. Every once in a while, you might go slalom or high jump. Since there was a ramp in my backyard, I skated vert most of the time. In fact, I competed in vert in the early years, but what I found out quickly, living in Vancouver, is it rains so much in the winter. You get five months of rain and crappy weather, so the ramp was hardly rideable from October to April. I had a covered garage where all my friends practiced freestyle, so we started getting better at freestyle very quickly because we could do it anytime, anywhere and we didn’t have to worry about the ramp being dry. Something else happened through that time too. Canada is a big country. It’s bigger than the United States, but we’re like 1/10th of your population. Since we had the ramp and this indoor freestyle spot going, it turned out that my five or six friends that were hardcore skaters came up to be some of the best in the country because we had all the best stuff to skate. It was like the Tony Hawk, Del Mar thing. It was always like, “The guys from Richmond are the guys to beat at a contest.” We all pushed each other. Out of the five or six of us that were really good, I wasn’t in the top. My friends were all better than me, but it made me push harder to get better.

Were you guys wanting to get sponsored or did you care about that?

Well, there were no movies or videos or YouTube then. We knew about guys like Tony Alva and Jay Adams, but we couldn’t really watch them, so we tried to go down to California in the summer so we could get a feel for what was going on. We have some pretty good talent up in Vancouver too, but our guys just weren’t getting that recognition because there wasn’t a skateboard magazine in Canada. We had guys that were skating vert at the same caliber and skating empty swimming pools like the guys in California. We just weren’t getting recognized at all, so we needed to bring this talent down to California to show them that there is talent throughout the world. Watching a guy skate Marina Skatepark in Marina Del Rey in ‘78, you’re on cloud nine and then you come back to Vancouver and try to emulate what that guy was doing.

When you went to Del Mar on those trips, what stood out in your mind?

There are so many huge vivid memories. Doug Saladino was one of my favorite skaters and, in ‘78, at a Del Mar contest, he did a rock ‘n roll slide three quarters of the way around the pool and I remember that sound. You had Alan Gelfand with the ollie and we witnessed that for the first time. That just blew me away. We skated all these incredible parks and we watched the contests. We witnessed all that stuff that is recognized nowadays as the first. I witnessed the first McTwist. I watched all the top riders in the world ride and I was in heaven. To see them skate firsthand was incredible. These guys were my idols and rock stars. I had pictures of them all over the walls. It was an amazing time to see skateboarding evolve.

Did you get to hang with any of them?

No. I was too shy and they were these idols that were just over and above. You couldn’t reach out. I felt like, “Oh, my God, there’s Steve Caballero. Oh my God, there’s Steve Olson.” I was just this little kid idolizing these guys. If you could actually walk close to them, you were on cloud nine.

When I rode Cherry Hill, it was the same thing. When pros came through you were like, “Holy shit!”

Cherry Hill was a hot spot. It’s the one place I never went, but I wanted to.

It was the best park in the world, at that time, and it was in New Jersey. [Laughs]

The same guy that built Cherry Hill also built Milpitas and San Francisco. We skated Milpitas all the time because it was close to us and that was my favorite park.

Yeah. It was Wally Hollyday. Cherry Hill was smooth, huge and ridiculous with four pools and a half pipe. It was an incredible park and then it was gone and the whole world fell out from under us. I was talking to P.D. at Skull Skates, and he said, “We still had our concrete in Vancouver, so we didn’t really feel it.” How do you explain to people that feeling when skateboarding started to die? In Canada, you guys kept all of your concrete, right?

Yes. We still had a lot of parks, but it was devastating to me when Skateboarder turned into Action Now. We went from holding contests at 10,000 seat arenas indoors to dead. Skateboarder magazine went back underground and I remember being totally pissed off. There were no skateboard magazines and the contest circuit in the United States had fallen apart. To you and me, it was devastating. It was exactly like you said. The world got pulled out from underneath me and I was pissed. The reason I was pissed is because I knew how fun skateboarding was and I wanted to portray that to every single person in the world. I was like, “It’s the best thing I’ve ever done in my life. There’s no way I’m going to let this die.” I was just going to do my own thing. So many of my friends dropped off and they were gone. I felt so alone, but I wasn’t going to follow the same trends they were. I skated more through the early ‘80s when it was dead to prove to everybody that it was going to come back. I was still going to skate because I love it.

We did the exact same thing. We built backyard ramps and kept skating. They can take the parks away, but I can’t quit skateboarding because I’m too addicted.

You went through that time too. So many adults would come up to me and say, “Okay, you did the skateboard thing. It was a fad. It’s gone now. Are you seriously going to still skateboard?” I was like, “Yeah.” I was just pissed.

Were you driven to go to college? Was there that kind of pressure on you?

There was peer pressure on me to do that. It’s like, “Hey, Kev, you better do something. How are you going to support a wife and kids if that ever happens down the road?” I was like, “I don’t know but I have to keep skating and I want to keep skating and I’m going to make this work.” I couldn’t see myself going to college and getting a real nine-to-five job. I had a job and I was making money, but there was no way in the world that somebody was going to take the coolest thing I’ve ever done on the planet away from me.

As far as sponsors go, the Bones Brigade started happening in the late ‘70s. What was your first encounter with Stacy?

I was skating in the Canadian circuit as an amateur and placing first in most of the contests. I was ranked number one in Canada for five years as an amateur and then came the death of skateboarding in ‘81. Nothing was really happening in Canada, plus, I’d done the Canadian thing and did well at all the contests. One or two guys that still skated were heading down south to enter the contests. In 1982, I went down there and entered the Del Mar contest. They had a pool riding and a freestyle event, so I was excited to go. I’d done the Oceanside contest as an amateur in ‘78 and ‘79, and then Steve Cathey had come up for a demo and he liked my skating, so he was sending me product from G&S. I went down to the contest in ‘82 and Stacy Peralta was there with the whole Bones Brigade: Caballero, Rodney, Tony, McGill… I was just blown away by the team. I entered the contest as a sponsored amateur for G&S. At the last minute they said, “There are not enough sponsored amateurs entered and there are not enough pros, so let’s run the two together.” All of a sudden, I was a pro skater for G&S without ever wanting to be. I remembered looking at the prize money. It was $150 for first, $100 for second and $50 for third, so I said, “You can actually win money? Cool. I’ll be pro. I can do that.” Rodney got first, Per got second and I got third in my first pro contest. I beat Rocco, another hero of mine. I was like, “How did that work?” I thought I was going to get tenth and I got third. I’m walking through the parking lot on cloud nine going, “Holy shit, I just won $50. I never got paid to skateboard in my life!”

Then it hits you that you’re actually a pro and you’re like, “Alright, I’m pro now.”

[Laughs] That’s exactly what went through my mind. $50 turned me into a pro skater. I walked through the gravel parking lot at Del Mar and Stacy Peralta was in that Volvo that he always drove the team around in. There was a group of skaters from Winnipeg, which is a city in the middle of Canada, that had gone down to hang out with Stacy before the contest. There were some great skaters that came out of Winnipeg and they called me this nickname, Lou Rigley, and they were hooked up with Stacy somehow, so Stacy knew me as Lou Wrigley. I’m walking through the parking lot after the contest and the window rolls down in Stacy Peralta’s Volvo and Stacy goes, “Hey, Lou Wrigley!” I’m like, “Oh my God. Stacy Peralta knows my nickname and he’s calling me over to the freaking car.” I was super nervous. I’ve got Audrey there who is my wife now but was my girlfriend at the time. I walk up and Stacy goes, “Hey, Kevin. You skated awesome. How would you like to ride for the Bones Brigade?” I was like, “Oh my freaking God!” [Laughs] I was soaring at that point. I barely slept that night. I was like, “Oh my God, I got asked to be on the Bones Brigade.” The rest is history. Stacy and I built a great relationship and then later he made me a team manager for some of the tours.

That must have been a high and then you had tell G&S that you were going to quit the team. How did you go about telling G&S? Were they cool about it?

I hadn’t really looked at it from every aspect. I knew that I wasn’t truly on G&S. It was just flow, but I’ve always been the type that didn’t want to burn any bridges, so the next day, I got in touch with Steve Cathey and said, “Look, this is what’s being offered to me. I totally appreciate the product.” Even before I could finish talking to him, he was like, “Kevin, you got offered to be on Powell. We were just giving you product. Go to Powell.” So I was able to move from G&S over to Powell.

Wow. That’s cool.

It was a pretty incredible day. That was a turning point. I came back to Vancouver and just wanted to skate 24/7 because I was on such a high to impress Stacy and prove that I was worthy of a team like that.

Did they want you to move to California or did you stay based in Vancouver?

At first, I was thinking about it. I knew where freestyle stood in the scheme of things. I knew Rodney’s board had just come out. The next one was going to be Per’s, so I knew I was a couple years away from getting a board. Stacy brought me up to speed on that. They’d ask the questions about me living down there, but they also knew that I’d just recently gotten married. Plus, I wanted to show the world that Vancouver is one of the raddest places on the planet. I wanted to prove to people that Vancouver had a lot going on, so I was constantly egging Stacy on, “You have to get up here. You have to see some of the parks. You have to see all the stuff going on.” I think Stacy realized quickly that I was planted in Vancouver, so there wasn’t a lot of pressure to move down there. It didn’t help my career not being down there because I wasn’t in front of the magazines. I knew Per was getting a lot more coverage than I was just because he lived down there.

For better or worse, you’re in Vancouver. As long as Stacy wasn’t sweating it, it’s all good, right?

Exactly. I realized on one side it was good for me, and on the other side, it wasn’t.

Were they paying you? How did you survive? You’re riding for the Bones Brigade. Were you working for them?

I was really lucky. I worked for my dad part time when there was nothing going on in skateboarding, but what happens to nearly any freestyler is once you get good enough, you can start doing shows and demos. Every weekend through spring and summer, I was doing shows somewhere. Now I was a pro skater and I had an agent working for me that would set me up with all of these demos at these fairs and malls. You could make decent money by doing that. Plus, it helped me come out of my shell a little. I was a pretty shy, skinny scrawny kid, so it helped me get out of that and deal with the public more because you had to skate in front of hundreds of people. I learned how to announce and started building the confidence to deal with that. That was a tremendous help when I started dealing with Powell. Powell was bringing me to the odd demo down in California and they started touring in ‘84.

Were you on that tour?

Yeah. By that time, I had built quite a relationship with Stacy. I was a few years older than the rest of the guys, so I was put in charge of making sure we were at the right place at the right time because people were waiting to watch us skate.

Stacy could depend on you.

Yeah. Stacy picked up on that really quickly and he started putting me in charge of the different tours. It was like, “We want you as a skater on the tour, but we also want you to do the driving, make sure that the hotel bookings happen and keep the guys organized. The business relationship started to build, so they could put their trust in me knowing that, if I was on the road, things were going to happen.

Were you into having that responsibility?

I was completely stoked. I was thinking I was under all these guys. I still idolized Cab, Rodney and Tony and I’m on tour with these mega superstars. I didn’t feel worthy, so I tried to do my part to make sure that I was prepping Stacy and George on the business side and making sure all these things were going to happen on schedule. That was my way of proving myself to the team, but also on the other side too.

Who would be in the van with you on a typical tour, like that first tour?

The very first tour I went on, it was Cab, McGill, and Eric Sanderson, one of the amateurs for Powell. They usually sent three pros and one am. They tried to send one freestyler, two vert guys and one street guy when street started to come in.

Did all those guys get along? Was it cool?

In most instances, everybody got along. What tended to happen was that there were basically two or three tour managers. McGill would run it sometimes because he had his act together. There was Todd Hastings, the team manager, that would run the tour and there was me. In ‘87, the tours were getting bigger and I always seemed to get the skaters that would get into trouble.

[Laughs] Tell the story.

Okay. So you had Jesse Martinez, Tommy Guerrero and Jim Thiebaud. This was when Powell was really pushing street skating. They knew that was the new hot thing, so they were trying to push their street skaters on the road more than the freestylers and vert skaters because they knew that street was where the big dollars were going to be. The problem with the street guys is that they only liked traveling when I was the tour manager, so I’d get a call from Todd Hastings in California. He’d go, “Kevin, we’re starting to book this tour. I got you booked from this time to this time, but the street skater guys only want to travel with you.” It was the most chaotic time of my life traveling with guys like that because you’re either bailing them out of jail or paying for the hotel they’ve ruined. You’re trying to get them up in the morning. They’re super good guys, but it was trouble every single night and you’re always dealing with a situation.

Did they resent you for busting their balls or did they know it was your job and they were cool with you?

Yeah. They weren’t out to get me and make my life more difficult. It was just their lifestyle. Most of those guys wouldn’t even travel with a duffel bag. They would just come with the clothes on their back and, at the next demo, they would take all the stuff from the shop and bill George for it. After a demo, they’d give their t-shirts away and just keep rotating the stock through every demo. I was like, “Wow. That’s a pretty cool way to travel.”

That’s full rock star style. Sick. [Laughs]

That’s how they were treated and that’s how the whole Bones Brigade thing went. We were like the Rolling Stones coming into town. [Laughs]

What were those demos like? You pulled into a town with a couple thousand people showing up for a demo?

In ‘84, skateboarding was starting to come back, but it wasn’t exploding to the point it did in ‘86. The demos that we did in ‘84 were maintainable because it was a 300-500 crowd. You had the mom and pop skateboard shop in a strip mall and they roped off an area in front. It was still at that relaxed state. By ‘86, it had tripled. We’d be expecting 500 people and it would turn into 3,000 people. Now you’ve got a problem. After we’d finish the demo, we’d start multiple autograph signings, and you just couldn’t get out of that and there was no security. There was nobody to help you out of a spot where you could get away from everything then come back to more of a sit down type of signing or get something to drink. It turned into chaos. Powell realized pretty quick that it was getting out of hand. They were trying to gear up the shops prior to us getting there on how to make security work, but that didn’t really happen until ‘89. There were a lot of shows that we did that were just like, “Whoa, there’s way more people here than anybody expected.”

Were Tommy, Jim and Jesse, stoked or were they kind of freaked out?

Yeah. There was that whole issue going on. We all loved to skate, but the hardest part were the signings after the demo. There were certain guys on the team, including me, that would make sure that we stayed for hours. I felt sorry for kids who had been waiting for hours with their parents. Other guys would be like, “I’m done. It’s 105 degrees. I’ve skated all day. I’ve signed for an hour and a half. Give me the keys to the van. I’m outta here.”

Is that where you had to step in and go, “No way, dude, you have to stay here?”

No. That was a fine line I had to walk. I didn’t want to get that aggressive and say, “Look, you have to stay here.” I’d just casually mention different things or show leadership and try to stay there. Sometimes they would come back to the scene. Guys like Tony Hawk were amazing professionals all the way through. Tony would stay until that last autograph was signed. It was three and a half hours later and Tony was still signing. He was the type that would just do that and there were guys that understood that and did it, but some street skaters had a different mentality. I understood the business model. If I could talk to some guy and sign an autograph and make that kid happy, that kid was more likely to buy a Powell product down the road. He would remember, “Kevin was pretty cool. He signed. He stayed for two hours.” It’s that whole program that’s going to make Powell happy. When you don’t have knowledge of that, you could really care less and it’s not about the company. It’s more about them. I totally get it. There are people who have a different mentality on how the whole business model works, right?

Yeah. They’re not thinking business. They’re thinking of their personal comfort. Once skateboarding becomes a job to some people they’re over it.

For sure. They gave their heart and soul to skating. Some of the stuff we had to skate was the worst. We had to skate on rough asphalt and crappy ramps in a 100-degree heat. They’d skate all day and then sign for an hour. Anybody in their right mind would say, “I’ve had enough.” They were rock stars. A guy like Tommy Guerrero should have been taken to a side area after the demo to able to towel off or have some water and then brought back to a nice shaded signing area. That didn’t happen. The organization wasn’t there. We didn’t have that. Not to take away anything from those guys, they did what they felt. They gave 110% and there were other people that would give 200%. Did I get frustrated with it sometimes? Yes. Sometimes I couldn’t even see the end of the line and I knew we’d still be signing for another hour, but it was all part of it.

[Laughs] It’s not easy being a rock star.

[Laughs] Well, when you’re traveling with guys like that, Tony would draw more people than traveling with somebody else. It was huge. By having those names when you traveled, you knew it was going to draw an extra thousand people.

Did you get any vibe that street skating was taking over vert skating? Were vert pros on Powell about the hype that the street pros on Powell were getting?

There were some guys that adapted to it, like Caballero. There were other guys that just hated it. My personal thing was Oceanside in ‘84, which was the very first street contest for NSA. I remember being there and going, “Okay, this is the death of freestyle and it’s going to hurt vert skating hugely.” I remember looking at some of those guys like, “That guy is a pro?” They only had six months of experience and they were making way more money than a guy like Rodney who was killing it and had tens of thousands of hours into it. Rodney is somebody who doesn’t belong on this planet because he’s so damn good. He’s a hard math problem. With street skating, it’s easier to learn for the average beginner. It just didn’t have the pro caliber yet. By ‘86, there was Natas and all the other street guys and it was like, “Holy shit.”

You’re with all the top-notch guys. You’ve got Tony Hawk who was the best vert skater in the world and some of the street pros for Powell were competitive in board sales with Tony Hawk. When I rode pro for Alva, I had boards out and I was just going, “Holy shit, street skaters are selling more boards.” It was a weird dynamic. I could imagine the conversations you heard on some of those tours. You’ve got Mike McGill who invented the 540, and he was getting outsold by a guy who can do a wall ride really high, right?

Exactly. There was behind the scenes animosity going on like, “Why is this happening?” McGill was one of the guys that was so pissed about where it was going. I thought, “Where is this all going to play out in the end?” I always looked at a guy like Rodney going, “How does this work? There’s the best guy on the planet. Look at Tony.” The whole vert thing was starting to slide too and the street kids were outselling some of these guys 30 to 1.

I can’t imagine what was going through Tony’s head. It’s a testament to his character to see where he’s at now. I remember the vibe of vert skating and us looking at those street skaters going, “What is going on? Now I have to learn street?”

[Laughs] Exactly. You can see that in the Christian Hosoi documentary. In the early ‘90s, he was like, “What am I going to do?”

There had to be a point where you’re going to these demos and there can’t be a vert ramp everywhere, so you’re probably booking way more demos for your street skating crew than your vert guys.

Exactly. By the late ‘80s, we started traveling with a jump ramp and mini ramps. Tony could do so much on a 6’ high ramp. They were definitely pushing the street aspects. When the local shop would bring out obstacles, it was all street-oriented.

Let’s talk about Mike Vallely. Were you there when Mike hit the Bones Brigade scene?

Yes. Well, let me go back for a sec. In that new Bones Brigade documentary, when they’re talking to Tommy, Tommy actually didn’t figure he was worthy when he first got on the Bones Brigade. He didn’t feel he deserved to be on and he was idolizing Tony and all the other guys, but that wasn’t the way he portrayed himself in the ‘80s. I was kind of shocked at what he said because he came across very, very, very confident back then. It was the same thing with Vallely. I was the tour manager when we picked that guy out in New Jersey. He was the new up-and-coming kid. Stacy said, “Get this kid and put him on the road.” I think he might have been 15 years old at the time. I had Cab, Tony and Adrian Demain in the van. I picked Mike Vallely up some place and he got in the van and sat down without saying anything and just put on headphones.

Where would you skate on these tours?

It was similar to what was happening in Vancouver in the ‘70s. When we would get to a spot, usually the demo site sucked as far as the stuff to skate, but then a group of the really cool skaters and the shop owner would go, “You have to go check this. This is the hottest spot we’ve got.” You would usually finish a demo, go shower, eat dinner and then meet up at some spot before you had to travel the next day. Every one of those towns had a hot spot to skate. Even if it wasn’t a good spot, you would always have to look at the scene like there are 50 people in this person’s backyard that really want to see us. You can’t just walk into somebody’s backyard and turn around and walk out, but I felt so sorry for them to have to skate it if it was crap.

I was interested to see if Mike was riding ramps with the vert guys because when I was in Jersey going to school and he turned pro, he was riding Groholski’s half pipe in New Brunswick. When he went on tour with you, did he skate any transition?

He did and I did the same thing. I would skate ramps too. Mostly everybody would join in. I can’t remember a time that people would go, “I’m not skating that.” If it was a good ramp, everybody would be skating it somehow.

You would be riding the ramp too?

Yeah. I’d skate mini ramps, but it depended on the session. If the session were already going on with five really incredible vert skaters, like Tony and Cab, then I wouldn’t join in. It depended on the caliber for me. I didn’t want to look like an idiot if the caliber was way over my head. [Laughs]

That’s so cool because back then, when you heard Kevin Harris, you were only portrayed as a freestyler. No one would ever know that you built a vert ramp in your backyard with pool coping.

Yeah. I’ve got pictures of me skating it from ‘77 to ‘81. I was placing good in vert until the tricks started getting really big in the early ‘80s. I was more from that trick generation where it was the slide reverts and grind coping reverts.

Ben Schroeder.

Exactly.

So you were traveling all through the ‘80s. What are some of the memorable incidents that happened on the road?

My most memorable story on the road was at Val Surf in Hollywood, which was the bigger of all of the demos. First of all, it’s California, and, second of all, it’s Val Surf, which was huge. This was ‘87, so skateboarding is booming. We all flew into Santa Barbara and we were driving to L.A. to do this show and this was before the cell phone, so you had no communication with anybody. As we were getting close, we blew a radiator hose, so we had to stop and get that fixed. By the time it was ready, we were an hour and a half late for the demo. As I’m driving up to Val Surf, thousands of kids were pushing the other way leaving the area. I looked up ahead and I see a police helicopter and a bunch of commotion going on and thousands of kids are coming out of Val Surf. Val Surf had way more skaters than they could handle. It was ‘87 and it’s booming, so they expected 500 and there was probably 2,000 skaters there. As they’re leaving, it only takes a few kids to go, “Oh my God look, it’s the Powell Peralta van. They’re here! They’re here!” Instantly, everybody started turning around and following us and stopping traffic and mobbing the van. I knew Val Surf was within a half a block, so I drove right into chaos. I knew it was not good. There were police up ahead and a police helicopter. The scene just didn’t look right. It just looked like they were trying to hurt these kids and I was driving smack into the middle of it. My first thought was, “Get me to the microphone. I’ll get control of this. These kids just want to see us skate. Get me over to the microphone. I’ll settle this whole thing down in 30 seconds.” As I get close, I get out of the van and it’s just mob territory. Kids are yelling, “Sign this! Sign this!” They’re shoving boards in my face. “Do you have a pen?” I’m saying, “We just want to do the show.” You hear police talking over their speakers going, “Clear the area!” You can hear sirens and everything. As I push through this mob, I could see the store up ahead. Meanwhile, I’d lost track of everybody else with me. I didn’t know where the hell they were. The next thing I know, I feel the scruff of my t-shirt being pulled, and somebody just hauls me backwards and puts me on the ground and throws handcuffs on me. It was the cops. They brought me to a cop car and slammed the door like, “You asshole. There are flipped over police cars. What are you guys doing?” I was like, “Look, we’re here. These kids just want to see us. Just get me to the microphone and I’ll settle this whole thing down.” They were like, “No. You’re arrested for causing a riot. You’re going to jail. We’ve got your buddies and they’re all going to jail.” So they drive us to the police station and the whole time I’m trying to say in a super nice polite way, “If you had just put me on the microphone, we could have done the show. I would have had it settled down. People would have watched us and we’re done.” They were like, “What’s this skateboard thing anyway? This is crazy. These kids are coming to see you guys skate? Who the hell are you guys?” It’s the ’80s, so we’re all drug dealers and devil worshippers, right?

Yeah, of course.

So we get into the police station and everybody else is there. One of the guys I had with me was Jesse [Martinez] and he’s not making it any easier. I’m sitting with Jesse and the sergeant comes in and he’s trying to figure out the situation. The sergeant says to Jesse, “Have you ever been arrested before?” Jesse looks at the guy and goes, “Yeah, for murder.” I was like, “Oh my God, Jesse.” I was like, “Get George Powell on the phone. This is not going to be good.” It’s chaos inside because Jesse was mouthing off, so I said, “Who is in charge here? Can we just go into a separate room and I’ll totally bring you guys up to speed?” I brought the guy into a quiet room and I said, “Look I’m married. My wife is pregnant with my first kid. I’m a family guy. This is skateboarding, but we’re not what you think we are.” He goes, “I don’t get this. How come all these kids were there for you guys? Who are you?” I say, “It’s the Bones Brigade. These guys are world famous. They make very good money from doing this. They travel the world and they’re rock stars in the skateboard industry.” They said, “Well, you can’t make money at skateboarding.” I was like, “I kid you not. One of the guys on our team, Tony Hawk, probably makes more in a month than you make in a year.” He goes, “Bullshit.” I said, “No. I’m being serious. You should check this guy out.” I calmed down the situation, but we still had to get out of Hollywood. They escorted us to the Hollywood City Limits.

You didn’t even get to skate?

Well, a couple months later we went back, because Val Surf felt sorry for the kids that wanted to see us, so they invited us back. Powell flew us all down there and we did another show and it was done very well with security and everything. I have tons of Jesse stories. Jesse and I got along fantastic, but talk about the trouble that guy could get into. Nearly ever night was chaos. He’d get charged for a lot of the stuff he did when he was on tour with us. One time, we had two days off, and the guys were going stir crazy because they weren’t doing shows for two days. I said, “We’re in California, so let’s go hang out at Disneyland for a day.” In hindsight, that was the wrong thing to do with a guy like Jesse because, as soon as a guy looked at Jesse the wrong way, he snapped. Jesse was putting money in one of the vending machines and some guy came up and mouthed off to him and Jesse just took the guy out. He completely wasted the guy. Jesse was staying in my room and he came back and his white shirt was red. It was covered in blood and he was like “Hide this shirt, man. The cops are coming.” He’s ripping up the shirt and flushing it down the toilet. That was just one of the things that happened. The next day we’re standing in line at a Magic Mountain ride when some guy looks at him the wrong way and he says something to this guy’s girlfriend. The guy goes, “Are you talking shit about my girlfriend?” Jesse lays him out and we got kicked out of Magic Mountain.

Jesse just knocked him out?

Totally. Jesse reached over three guys and completely knocked the guy out. Another time, they had a young girl that said she was 18. Her parents were really wealthy and they had the FBI tracking us down. George Powell phoned me up in the middle of a tour. I was announcing a demo and the shop owner was like, “You have to stop announcing. George needs to talk to you now.” I was like, “Hang on, I’m in the middle of announcing this demo.” They were like, “No. Now.” The shop owner takes over the mic and I go answer the phone. George goes, “Kevin, I just got a call. The FBI is on you. They’re following you. They’re going to be there in 20 minutes, so leave the demo now and take the girl to the Greyhound station because you guys are all going to get arrested for kidnapping.” I was like, “Holy shit!” Those are just three out of a hundred times. When I had those guys on the road, I phoned my wife every night and every time I talked to her a pretty major event had happened. She was like, “Okay, what happened today?”

Would you have to call Stacy and George too?

I would have to call George a lot of times just to bail us out financially. Either I needed money to get Jesse out of trouble because he had warrants out for his arrest and I needed to pay those off in order to get him out or I needed to deal with the hotel manager for some damage. It was typical things that you read about like when big rock bands like Led Zeppelin would be on the road. It was just like that. There were no problems that were mellow. It was all just crazy.

Were you getting compensated well for all that?

[Laughs] No. It wasn’t about that. I wanted to do the best I could for Powell because I felt so honored to ride for that company. I just did what it takes. I just dealt with it. I was like, “Okay, this happened.” These guys are adults. I can’t come down on them like, “Don’t you ever do that again.” I wasn’t going to treat them like that. We just moved on to the next thing. I handled it however I could handle it.

Let’s go to the other side of the spectrum, Tell me about how you were driving and Rodney Mullen got out of the car and just sat in the middle of a cornfield?

They always had one freestyler on the road, so I was never traveling with Rodney, but, one time, I was at the airport and they were supposed to come pick me up. We were in upstate New York and they were hours late. I was hanging out waiting for them to pick me up. The story came out later that they were driving to get me on some highway in the middle of nowhere and Rodney had one of those moments where he just freaked out. He goes, “Stop the van!” He jumped out and ran into some cornfield. He just took off and they couldn’t find him for three hours. [Laughs]

FOR THE REST OF THE STORY, ORDER ISSUE #73 AT THE JUICE SHOP…

SHARE THIS POST:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)