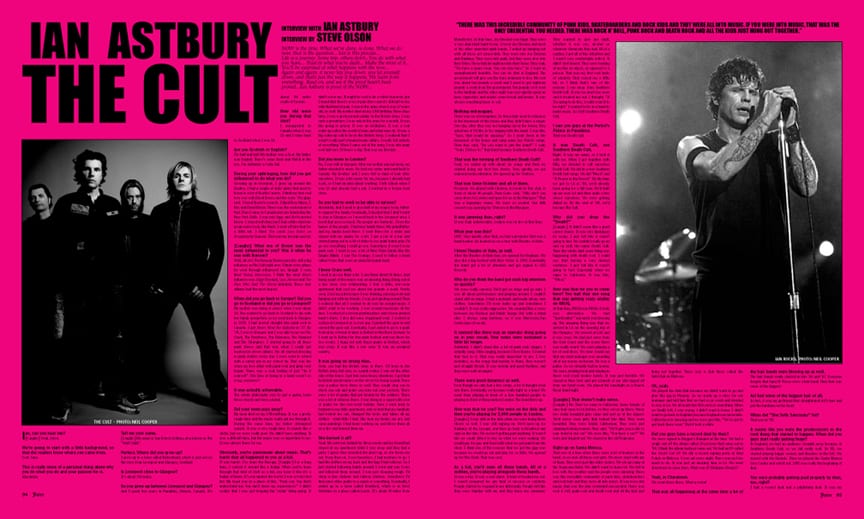

INTERVIEW WITH IAN ASTBURY

INTERVIEW BY STEVE OLSON

INTRODUCTION BY STEVE OLSON

PHOTOS BY NEIL COOPER

NOW is the time. What we’ve done, is done. What we do now, that is the question… Ian is this process… Life is a journey. Some trip, others don’t…You do with what you have… Trust in what you’re dealt… Make the most of it… You’ll be surprised at what happens with the now… Again and again, it never lets you down, you let yourself down, and that’s just the way it happens. We learn from everything. Read on, and see if the proof hasn’t been proved…Ian Astbury is proof of the NOW…

“THERE WAS THIS INCREDIBLE COMMUNITY OF PUNK KIDS, SKATEBOARDERS, AND ROCK KIDS AND THEY WERE ALL INTO MUSIC. IF YOU WERE INTO MUSIC, THAT WAS THE ONLY CREDENTIAL YOU NEEDED. THERE WAS ROCK N’ ROLL, PUNK ROCK AND DEATH ROCK AND ALL THE KIDS JUST HUNG OUT TOGETHER.”

Ian, can you hear me?

[Laughs] Yeah, Steve.

We’re going to start with a little background, so that the readers know where you came from.

Cool. Sure.

This is really more of a personal thing about why you do what you do and your passion for it.

Absolutely.

Tell me your name.

[Laughs] My name is Ian Robert Astbury, also known as the ‘Wolf Child’.

Perfect. Where did you grow up?

I grew up in a town called Birkenhead, which is just across the river from Liverpool and Glasgow, Scotland.

Is Liverpool close to Glasgow?

It’s about 250 miles.

So you grew up between Liverpool and Glasgow?

And I spent five years in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. It’s about 40 miles south of Toronto.

How old were you during that stint?

I immigrated to Canada when I was 11 and I came back to Scotland when I was 16.

Are you Scottish or English?

I’m half and half. My mother was a Scot. My father was English. There’s some Irish and Welsh in the mix. I’m definitely a Celtic kid.

During your upbringing, how did you get influenced to do what you do?

Growing up in Liverpool, I grew up around the Beatles. I had a couple of older aunts that used to listen to a lot of Beatles’ music. I think my first real love was with David Bowie and the early ’70s glam rock. I loved Bowie’s records. I liked Roxy Music, T. Rex and David Bowie. There was the evolvement of that. Then I came to Canada and saw bands like the New York Dolls. I was into Iggy and Berlin-period Bowie. I stayed with that, but I had a little stint into progressive rock, like Rush. I went off into that for a little bit. I liked The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway by Genesis. That was my lysergic period.

[Laughs] What era of Bowie was the most influential to you? Was it when he was with Ronson?

Well, all of it. The Ronson/Bowie period is still a big influence on The Cult right now. I think every phase he went through influenced me, though. I even liked Young Americans. I think the most direct influence was Ziggy Stardust, Low, Heroes and The Man Who Sold The World definitely. Those four albums had the most impact.

When did you go back to Europe? Did you go to Scotland or did you go to Liverpool?

My mother was dying of cancer when I was about 14. She wanted to go back to Scotland to die with her family around her, so we went back to Glasgow in 1978. I had moved straight into punk rock in Canada. I got Never Mind the Bullocks in ’77. By ’78, I was in Glasgow and I was able to go see The Clash, The Banshees, The Ramones, The Damned and The Stranglers. I started going to all these punk shows and that was when I really got involved in street culture. We all started dressing in punk clothes every day. I even went to school with a safety pin in my school tie. That was the when my love affair with punk rock and glam rock began. There was a real feeling of just ‘do it yourself’. The idea of being in a band wasn’t so crazy, you know?

It was actually achievable.

The whole philosophy was to get a guitar, learn three chords and form a band.

Did your mom pass away?

My mom died on my 17th birthday. It was a pretty rough time and the music really got me through it. During the same time, my father attempted suicide. It was a very rough time. It sounds like a cliche, but we were really poor. We didn’t have anything. It was a difficult time, but the music was so important to me. It was always there for me.

Obviously, you’re passionate about music. That’s harsh that all happened to you as a kid.

It was harsh. I’ve done the therapy. [Laughs] For a long time, I carried it around like a badge. When you’ve been through that kind of stuff as a kid, you wear it like it’s a badge of honor. It’s you against the world. I was a real rebel kid. My head was in a place of like, ‘Fuck you. You don’t understand me. You don’t know my experiences.’ I didn’t realize that I was just keeping the ‘victim’ thing going. It didn’t serve me. It might be cool to be a rebel character, but I found that there’s a lot of pain there and it’s difficult to live with that kind of pain. I was in the army when I was 17 years old, as well. My mother died on my 17th birthday. Three days later, I was a professional soldier in the British Army. I was such a greenhorn. I was only in the army for a month. It was like going to prison. It was an institution. It was a real wake-up call in the world of men and what men do. It was a big wake-up call to be in the British Army. I realized that I wasn’t really part of mainstream culture. I really felt outside of everything. When I came out of the army, I was into punk rock full-core 24 hours a day. That was my lifestyle.

Did you move to London?

No, I was still in Glasgow. After my mother passed away, my father decided to move. He took my sister and went back to Canada. My brother and I were left to kind of look after ourselves. It was a lot easier for me, because I already had a job, so I had an idea about working. I left school when I was 16 and already had a job. I worked in a frozen food store.

So you had to work to be able to survive?

Absolutely. And I used to give half of my wages to my father to support the family. Eventually, I decided that I didn’t want to stay in Glasgow, so I moved back to the Liverpool area. I loved that area so much. The people are fantastic. I love the humor of the people. I had nice family there. My grandfather and my auntie lived there. I went there for a while and stayed with my auntie for a bit. I got a job at a bar and started going out to a lot of clubs to see punk bands play. I’d go see everything I could go see. Sometimes it wasn’t even punk rock. I went to see a lot of New Wave bands like the Simple Minds. I saw The Cramps. I used to follow a band called Crass that were an anarchist punk band.

I know Crass well.

I used to go see them a lot. I saw them about 36 times. Just being a part of live music was an amazing thing. Being out at a live show was exhilarating. I had a little, one-room apartment that cost me about ten pounds a week. Pretty soon, I lost my job because I was drinking, missing work and hanging out with my friends. I was just goofing around. Then I realized that all I wanted to do was be around music. I didn’t want to be working. I was around musicians all the time. I worked at a screen-printing place and screen-printed band t-shirts. I also did some stagehand work. I worked at a place in Liverpool as a crew guy. I pushed the gear in and carried the gear out. Eventually, I got asked to go to a punk festival by a friend of mine in Belfast in Northern Ireland. So I went up to Belfast for this punk festival and was there for two weeks. I hung out with these punks in Belfast, which was crazy. It was like a war zone. It was an occupied country.

It was going on strong then.

Yeah, you had the British army in there. I’d been in the British Army, but now, as a punk rocker, I was on the other side of the fence. I got into some heavy situations. I got beat by British paratroopers on the street for being a punk. There was a police force there as well. They would stop you to check you out and make you turn out your pockets. There were a lot of punks that got beaten by the soldiers. There was a lot of violence there. I was living in a squat with a lot of punks for this two-week holiday. Then I went back to England to my little apartment, only to find that my landlady had locked me out, changed the locks and taken all my clothes – what little I had. She took my books, my art, and some paintings I had been working on, and threw them all on a fire and burned them up.

She burned it all?

Yeah. My rent was behind for three weeks and my friend had stayed at my apartment while I was away and they had a party. I guess they smashed the place up, so she threw me out. From then on, I was homeless. I had nowhere to go. I had the clothes on my back and the bag I had with me. So I just started following bands around. I went and saw Crass and followed them around. I was just sleeping rough. I’d sleep in bus stations and railway stations. Sometimes I’d find some other punks in a squat or something. Eventually, I ended up in a town called Bradford, which is in West Yorkshire in a place called Leeds. It’s about 30 miles from Manchester. At that time, Joy Division was huge. They were a very important band to me. I loved Joy Division and most of the other anarchist punk bands. I ended up hanging out with all these art school kids. They were into Joy Division and Bauhaus. They were into punk, but they were also into New Wave. These kids brought me into their home. They said, ‘We have a spare room. You can stay here.’ So I went on unemployment benefits. You can do that in England. The government will give you the bare minimum to live. My rent was about ten pounds a week and I used to get eighteen pounds a week from the government. Ten pounds of it went to the landlady and the other eight was very quickly spent on beer, cigarettes and maybe some bread and beans. It was always something basic to eat.

Nothing extravagant.

There was no extravagance. So these kids used to rehearse in the basement of this house and they didn’t have a singer. One day, after they saw me hanging out in the house, they asked me if I’d like to try singing with the band. I was like, ‘Sure, that would be amazing.’ So I went down in the basement of the house and sang some Sex Pistols songs. Then they said, ‘Do you want to join the band?’ I said, ‘Yeah. I’d love to.’ That band became Southern Death Cult.

That was the forming of Southern Death Cult?

Yeah, we ended up with about six songs and then we started doing our first few shows. Very quickly, we got national media attention. We opened up for Chelsea.

That was Gene October and all of them.

Precisely. We played with Chelsea, in Leeds in this club, in front of about 40 people. Then Gene said, ‘Why don’t you come down to London and open for us at the Marquee.’ That was a legendary venue. We were so excited. Our fifth concert was opening for Chelsea at the Marquee.

It was jamming then, right?

It was truly unbelievable. London was on fire at that time.

What year was this?

1982. Very quickly after that, we had a promoter that was a band booker. He booked us on a tour with Theatre of Hate.

I know Theatre of Hate, as well.

After the Theatre of Hate tour, we opened for Bauhaus. We also did a big festival with New Order in 1982. Eventually, the band got a lot of attention and got signed to CBS Records.

Why do you think the band got such big attention so quickly?

We were really earnest. We’d get on stage and go nuts. I was all about performance and jumping around. I couldn’t stand still on stage. I had a mohawk and made all my own clothes. Sometimes I’d wear make up and sometimes I wouldn’t. It was really aggressive. We sounded like a cross between Joy Division and Public Image Ltd. with a tribal vibe. I always sang baritone, so it was Morrissey/Ian Curtis-type of vocals.

It seemed like there was an operatic thing going on in your vocals. Your notes were sustained a little bit longer.

Definitely. I didn’t shout like a lot of punk rock singers. I actually sang. I like singing, because I love Bowie. I wanted that feel to it. That was really important to me. I love melodies, so the songs had melody to them. They weren’t just straight thrash. It was melody and good rhythms, and they were well-arranged.

There were good dynamics as well.

Even though we only had a few songs, a lot of thought went into them. Eventually, we became really tight as a band. We went from playing in front of a few hundred people to playing in front of thousands in London. The band blew up.

How was that for you? You were on the dole and then you’re playing for 2,000 people in London.

[Laughs] I was still on the dole when we were doing those shows as well. I was still signing on. We’d open up for Bauhaus at the Lyceum, and then go back to Bradford and sign on the dole. We weren’t getting paid anything. It wasn’t like we could afford to live on what we were making. We would pay for gas and food with what we got paid from the show. I think one of the reasons that we got the gigs was because we would go out and play for so little. We opened up for The Clash. That was cool.

As a kid, you’d seen all these bands. All of a sudden, you’re playing alongside these bands.

It was a trip. It was a real shock. It kind of freaked me out. I wasn’t prepared for any kind of success or celebrity. People started to respond to me differently. People felt like they were familiar with me and they knew me somehow. They wanted to give me stuff, whether it was sex, alcohol or whatever chemicals they had. All of a sudden, I got all of this attention and I wasn’t very comfortable with it. It didn’t feel honest. They were looking at me like an object, as opposed to a person. That was my first real taste of celebrity. That scared me a little bit, so I think that’s one of the reasons I ran away from Southern Death Cult. It was too much too soon and it freaked me out. I thought, ‘If I’m going to do this, I really want it to be right.’ I wanted to be in a band to make music. So I left Southern Death Cult.

I saw you guys at the Perkin’s Palace in Pasadena.

That was Death Cult.

It was Death Cult, not Southern Death Cult.

Right. It was my name, so I took it with me. When I got together with Billy, we decided to call ourselves Death Cult. We did do a few Southern Death Cult songs. We did ‘Moya’ and ‘A Flower in the Desert’. By the time we got to LA in ’84, we’d already been going for a full year. We’d built up our own set and done quite a few shows ourselves. We were getting dialed in. By the end of ’84, we’d become The Cult.

FOR THE REST OF THE STORY, ORDER ISSUE #63 BY CLICKING HERE…

SHARE THIS POST:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)