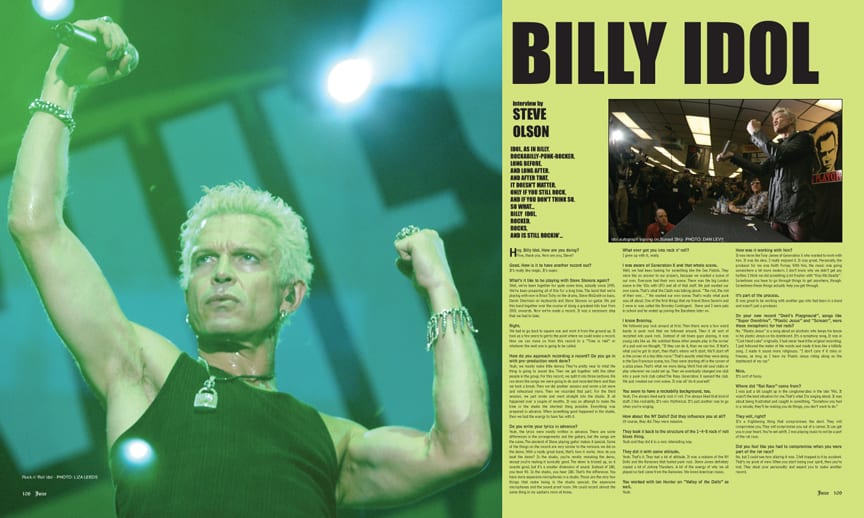

INTERVIEW BY STEVE OLSON

INTRODUCTION BY STEVE OLSON

PHOTOS BY DAN LEVY and LIZA LEEDS

Idol, as in Billy. Rockabilly-punk-rocker, Long before, and long after. And after that, it doesn’t matter, only if you still rock, and if you don’t think so, so what… Billy Idol, rocked, rocks and is still rockin’…

“THEY’VE BEEN SAYING ROCK IS DEAD EVER SINCE IT BEGAN. THEY SAID ROCK WAS DEAD WHEN ELVIS WENT INTO THE ARMY. THEY SAID ROCK WAS DEAD WHEN THE BEATLES BROKE UP. THEY SAID ROCK WAS DEAD WHEN BUDDY HOLLY DIED. THEY SAID ROCK WAS DEAD WHEN THE SEX PISTOLS BROKE UP. ROCK N’ ROLL AIN’T DEAD UNTIL I’M DEAD.”

Hey, Billy Idol. How are you doing?

Fine, thank you. How are you, Steve?

Good. How is it to have another record out?

It’s really like magic. It’s super.

What’s it like to be playing with Steve Stevens again?

Well, we’ve been together for quite some time, actually since 1995. We’ve been preparing all of this for a long time. The band that we’re playing with now is Brian Tichy on the drums, Steve McGrath on bass, Derek Sherinian on keyboards and Steve Stevens on guitar. We put this band together over the course of doing a greatest hits tour from 2001 onwards. Now we’ve made a record. It was a necessary step that we had to take. We had to go back to square one and work it from the ground up. It took us a few years to get to the point where we could make a record. Now we can move on from this record to a “Time in Hell” or whatever the next one is going to be called.

How do you approach recording a record? Do you go in with pre-production work done?

Yeah, we mainly make little demos. They’re pretty near to what the thing is going to sound like. Then we get together with the other people in the group. For this record, we split it into three sections. We ran down the songs we were going to do and recorded them and than we took a break. Then we did another session and wrote a bit more and rehearsed more. Then we recorded that part. For the third session, we just wrote and went straight into the studio. It all happened over a couple of months. It was an attempt to make the time in the studio the shortest thing possible. Everything was prepared in advance. When something good happened in the studio, then we had the energy to have fun with it.

Do you write your lyrics in advance?

Yeah, the lyrics were mostly written in advance. There are some differences in the arrangements and the guitars, but the songs are the same. The element of Steve playing guitar makes it special. Some of the things on the record are very similar to the versions we did on the demo. With a really great band, that’s how it works. How do you beat the demo? In the studio, you’re mostly remaking the demo, except you’re making it sonically good. The demo is tricked up, so it sounds good, but it’s a smaller dimension of sound. Instead of 180, you hear 90. In the studio, you hear 180. That’s the difference. You have more expensive microphones in a studio. Those are the very few things that make being in the studio special; the expensive microphones and the sound proof room. We could record almost the same thing in my upstairs room at home.

Whatever got you into rock n roll?

I grew up with it, really.

I was aware of Generation X and that whole scene.

Well, we had been looking for something like the Sex Pistols. They were like an answer to our prayers, because we wanted a scene of our own. Everyone had their own scene. There was the big London scene in the ’60s with UFO and all of that stuff. We just wanted our own scene. That’s what the Clash was talking about. “The riot, the riot of their own.” We wanted our own scene. That’s really what punk was all about. One of the first things that my friend Steve Severin and I were in was called the Bromley Contingent. Steve and I were pals in school and he ended up joining the Banshees later on.

I know Bromley.

We followed pop rock around at first. Then there were a few weird bands in punk rock that we followed around. Then it all sort of morphed into punk rock. Instead of old blues guys playing, it was young cats like us. We watched these other people play in the corner of a pub and we thought, “If they can do it, than we can too. If that’s what you’ve got to start, then that’s where we’ll start. We’ll start off in the corner of a tiny little room.” That’s exactly what they were doing in the San Francisco scene, too. They were starting off in the corner of a pizza place. That’s what we were doing. We’d find old soul clubs or play wherever we could set up. Then we eventually changed one club into a punk rock club called The Roxy. Generation X opened the club. We just created our own scene. It was all do-it-yourself.

You seem to have a rockabilly background, too.

Yeah, I’ve always liked early rock n roll. I’ve always liked that kind of stuff. I like rockabilly. It’s very rhythmical. It’s just another way to go when you’re singing.

How about the NY Dolls? Did they influence you at all?

Of course, they did. They were massive.

They took it back to the structure of the 1-4-5 rock n roll blues thing.

Yeah and they did it in a very interesting way.

They did it with some attitude.

Yeah. That’s it. They had a lot of attitude. It was a mixture of the NY Dolls and the Ramones that fueled punk rock. Steve Jones definitely copied a lot of Johnny Thunders. A lot of the energy of why we all played so fast came from the Ramones. We loved American music.

You worked with Ian Hunter on “Valley of the Dolls” as well.

Yeah.

How was it working with him?

It was more like Tony James of Generation X who wanted to work with him. It was his idea. I really enjoyed it. It was great. Personally, the producer for me was Keith Forsey. With him, the music was going somewhere a lot more modern. I don’t know why we didn’t get any further. I think we did something a lot fresher with “Kiss Me Deadly.” Sometimes you have to go through things to get anywhere, though. Sometimes these things actually help you get through.

It’s part of the process.

It was great to be working with another guy who had been in a band and wasn’t just a producer.

On your new record “Devil’s Playground”, songs like “Super Overdrive”, “Plastic Jesus” and “Scream”, were those metaphoric for hot rods?

No. “Plastic Jesus” is a song about an alcoholic who keeps his booze in his plastic Jesus on his dashboard. It’s a symphony song. It was in “Cool Hand Luke” originally. I had never heard the original recording; I just followed the meter of the words and made it less like a hillbilly song. I made it sound more religiouso. “I don’t care if it rains or freezes, as long as I have my Plastic Jesus riding along on the dashboard of my car.”

Nice.

It’s sort of funny.

Where did “Rat Race” come from?

I was just a bit caught up in the conglomerates in the late ‘90s. It wasn’t the best situation for me. That’s what I’m singing about. It was about being frustrated and caught in something. “Somehow you feel in a minute, they’ll be making you do things, you don’t want to do.”

They will, right?

It’s a frightening thing that compromises the devil. They will compromise you. They will compromise you out of a career. It can get you in your heart. You’re set adrift. I was playing music to not be a part of the rat race.

Did you feel like you had to compromise when you were part of the rat race?

No, but I could see how alluring it was. I felt trapped in it by accident. That’s my point of view. When you start losing your spirit, then you’re lost. They steal your personality and expect you to make another record.

Did you ever imagine, when you were a kid, that you’d be Billy Idol?

No.

Never?

I had no idea. In 1975 and 1976, you couldn’t get a job, no matter what you did. Even if you were a college graduate or a garbage man, it didn’t matter. There were no jobs. There were no jobs for a long time. You either went on the dole or tried to do something creative, so we did what we loved. It’s just great that there was someone like Malcolm McLaren pushing people like the NY Dolls and then helping the Sex Pistols get together. He created a focal point for all of us in London at the time. We all focused around Malcolm and the shop. It wasn’t planned out at all. It was never like, “Oh, I’m going to be a musician.” I never thought I’d be a musician. No one, including my dad, thought I’d ever be a musician. I just played the guitar and sang and stuff. It was a dream and it ended up coming true.

FOR THE REST OF THE STORY, ORDER ISSUE #59 BY CLICKING HERE…

SHARE THIS POST:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)